Thao bent down to put her backpack back on, pulling her cap closer to her forehead. In front of her was a small path hidden by bushes, crossing the hillside, the place her grandfather had once mentioned in the most solemn voice:

- That is La Tham slope. The whole unit retreated there. Without that road, I wouldn't be here to tell you this story.

It had been ten years since he had passed away. Thao had only a handwritten note with a few smudged lines of ink and fragmented narration from her mother. Yet now, she had returned here alone, not exactly to do her homework, not exactly to find that slope again.

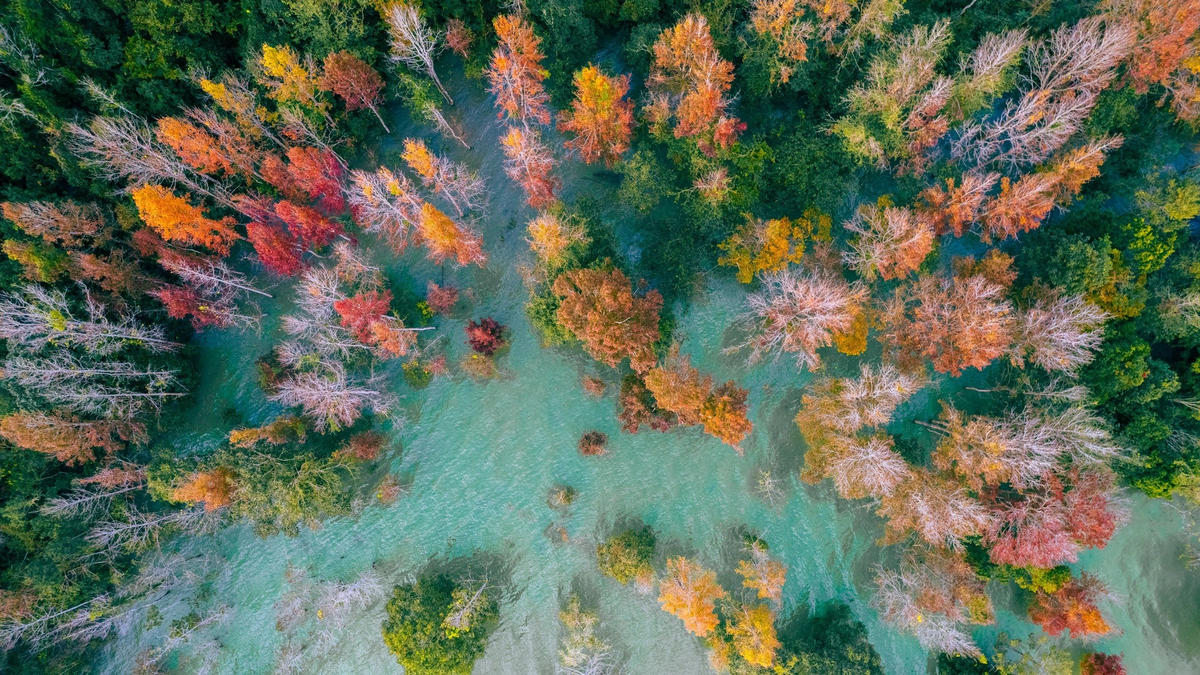

The afternoon descended quickly on the mountainside. The sunlight was only a thin line across the anise forest, making the shadows on the dirt road lengthen as if trying to reach something that was gone. Thao walked slowly, her back soaked with sweat, but her eyes did not leave the faint depressions on the ground. The more she walked, the quieter her heart became, as if she were entering a place that had been visited before, and now only the sound of sighs in the wind remained. Thao followed the sloping dirt path leading down to the end of the village, where there was an old stilt house with moss covering one side of the steps. That was the address her mother had written in her last message: When you get to the village, ask for Mr. Khuyen. He still remembered a lot but did not talk much.

Mr. Khuyen's house was located at the end of Na Lam village, leaning against the hillside, its roof covered with faded cement sheets, moss growing all over the porch. Under the stone steps, several pots of medicinal leaves were drying, tilted in the afternoon wind. The sound of the pestle pounding rice bran echoed softly from the house next door, in a very quiet space, so much so that Thao could hear the sound of birds flapping their wings through the plum trees beside the fence.

Thao tiptoed up the wooden stairs, her palms still sweaty from the long journey. She tapped lightly on the wooden post. No one answered immediately. There was only the crackling of the fire in the kitchen and the slow sound of a knife cutting wood inside the stilt house. Before Thao could call out a second time, a deep, slightly hoarse but clear male voice rang out from behind the screen:

- You're the one looking for the old slope, right?

She was startled.

- Yes! My name is Thao, I'm from Hanoi , I'm Mr. Loc's niece who used to be in the guerrilla team...

Her voice faded away, drowned out by the sound of the wind blowing through the walls. Before she could say anything more, the man's voice continued from inside the dark room:

- Loc's nephew, the flute player in the middle of the mountain? You're a history student, right?

Thao stood still, stunned. She didn't expect him to know, and even less expected that someone would remember that old nickname, the name only her grandfather's comrades called him. The man with a salt and pepper beard, a hunched back, and a cane stepped out. Thao took off her backpack and stood still. Mr. Khuyen gestured with his hand:

- Come in. If you want to ask about the slope, you have to come with me. But not today.

Thao nodded, still clutching the backpack strap.

- Yes! I want to redraw the map of La Tham slope. If you still remember the retreat route that year, I would like to go with you.

Mr. Khuyen looked at her, his eyes squinting in the late afternoon sunlight. Then he smiled, a toothless smile:

- I remember, but that line is no longer under my feet. It is in my back, in the scar on my calf, on the night I walked backwards to pull the injured person. To draw, you have to use not only your hands, but also your ears and knees.

Thao nodded slightly. She did not fully understand those words, but something in her heart had just been awakened, a trust or a silent promise that the old slope had not disappeared, if anyone dared to walk back with all their heart.

The next morning, the weather was chilly. The wind from the anise forest blew through the valley, carrying the smell of damp dew and young leaves. The scattered crowing of roosters echoed from the village entrance. Thao woke up early. She folded the blanket, tied her notebook, and put the recorder in her pocket. In the kitchen, Mr. Khuyen had made tea early, his rubber slippers neatly placed on the bottom step of the stairs, his bamboo stick propped up next to his worn palm hat. As she stepped out from the daisy hedge, Thao heard him say:

- I was seventeen when I went up this hill. Now I'm ninety. But the road hasn't changed much. Maybe my eyes have changed.

The trail wound along the mountainside. Thao followed behind, trying to avoid stepping on the mossy rocks, even though Mr. Khuyen had never told her to do so.

- Back then, no one broke leaves in the forest, they just brushed them away with their sleeves. It wasn't because they were afraid of getting lost, but because they were afraid of making noise.

After walking for about an hour, they came to a flat stone slab blocking the path, its surface covered with moss, but its edge was concave as if someone had sat there for a long time. Mr. Khuyen stood still, his head slightly tilted, his eyes squinted.

- Right here, that year, someone was injured. We couldn't take them with us. My mother left a trumpet at the foot of this rock. She told me to stick it in the ground and make a call. If anyone survived, they would know how to return.

Thao looked around. The wind in this corner of the mountain was not strong. Forest leaves covered the ground. Among the dry leaves, a round-edged stone slab had a diagonal crack like the line of a human spine. She knelt down, gently brushed away each layer of leaves, and touched the cold, damp stone. Her hand touched a dent that fit perfectly into her palm, as if someone had placed their hand exactly like this. She looked up and saw that Mr. Khuyen had pulled off his head scarf, wiped the sweat from his forehead, and said softly:

- If there's something down there, it's because it doesn't want to go yet. If there's nothing, don't feel sorry. Because if someone comes back, this place will be full.

Thao's eyes stung, even though the wind was blowing against her. She took a slow breath, reached behind her, and took out the small knife. Then the sound of the knife tip hitting something hard. The sound was dry and sharp, not stone, nor wood. She trembled and dug it up. A piece of dull metal appeared, curved at the top, hollow and cracked along the body. It was a broken brass trumpet, rusted but still holding its shape. Beside it was a piece of wrinkled red cloth, no longer intact, the edges rotten. Thao burst into tears:

- My grandfather was the one who took the injured man out of the forest afterwards and also the one who buried the trumpet next to the rock. He always mentioned the Dark Leaf Slope.

Thao wrapped the flute in a cloth and put it back in her pocket. A choking feeling rose in her heart, as if she had caught a call, but did not know how to blow it properly. The sun was just slanting over the forest shoulder, casting a ray of sunlight on the stone slab. The flute, though rusty, still shone a bit of red and gold like the eyes of someone who had gone back to keep the footsteps of the person behind.

The afternoon fell quickly as the two returned to the village. The stream at the head of the village receded, revealing green rocks like fish backs floating in the basin of the late afternoon sunlight. The sunset streamed down the stilt house roof, sliding over the woven bamboo mats used to dry rice. The wind blew with the smell of kitchen smoke and burnt corn husks. Thao washed her hands at the gable end of the house and then brought the trumpet wrapped in a towel to Mr. Khuyen's house. The villagers began to flock to her. Some were curious, others followed the rumors. A middle-aged man asked:

- Is that what was used during the uprising? Are you sure?

Thao nodded slightly:

- I can't confirm it yet, but it's in the correct position as described. If the restoration is good, I can ask to bring it back to school as a living relic model.

A murmur arose. An old woman wearing an indigo scarf spoke softly but firmly:

- If it's still in the ground, it belongs to the ground. People buried it here because they couldn't take it away. Why should we take it now?

Thao was startled. She gently squeezed the edge of the cloth covering the trumpet.

- But if left here, no one will know, it will stay silent forever. If we bring it back to restore, maybe more people will remember, I think.

Mr. Khuyen's face showed no expression. Only when he got closer to the trumpet, he looked out the door, at the distant mountains, and said in a steady voice:

- People who stay in the forest don't need anyone to remember them, don't need to appear in museums. They need someone to go through the same places they went and understand why they did what they did.

Everyone fell silent. Thao bowed her head. She was confused between her responsibility as a history student and the vague call of the land and the forest. The old woman spoke again:

- You can take it. But what if one day someone comes back here looking for that trumpet?

The wind rose, the red cloth covering the trumpet fluttered slightly. Thao looked down and saw a crack on the bronze body and a stain of dried mud that had not been completely washed off. She carefully wrapped the trumpet but did not put it in her backpack, but placed it in Mr. Khuyen's hand and said softly:

- I would like to take photos to preserve memories for my family. Please take them to the local museum to hand over to the management agency!

Thao postponed her return trip. She applied for an extension of her research at Na Lam village, a decision that surprised her supervisor and left her mother calling three times to ask again:

- What do you plan to do there? What if the research doesn't come to a conclusion?

She just replied:

- History is not in the report, mom.

The next morning, she and Mr. Khuyen set up a wooden board on the drying floor of the stilt house, pasting pictures she had printed from documents: a picture of La Tham slope, a picture of the flag. The trumpet lay solemnly on a new indigo scarf. The children came, some carrying bird cages, some carrying their younger siblings on their backs. Thao spread out a mat, not calling this a classroom, just saying very softly:

- Do you know, the road you went to pick blackberries yesterday was once a military retreat?

They shook their heads, their eyes fixed on the photos and the strange trumpet. Thao's voice was still as soft as mist:

- So today, I will tell that story. But you have to sit still and listen with both your ears and your feet.

The children were curious and gradually quieted down. Thao used charcoal to draw a diagram on a wooden board.

- This is where a soldier was wounded. This is where a mother left her trumpet.

Anyone passing by there must bow their heads.

Mr. Khuyen sat beside him, not interrupting, only occasionally reminding:

- Back then there were no maps. We just looked at the stars and listened to the wooden fish.

In the afternoon, Thao led the children back up the slope, each with a stone to mark the path. One of them asked:

- Sister, did the dead see me walk by?

Thao paused, looking up at the windless treetops:

- If you call their names right where they lie, they will surely hear.

In the evening, the little girl brought a young star anise branch and gave it to Thao:

- Sister, I broke it where the trumpet was buried. I planted it in the ground. If anyone gets lost in the future, the tree will point them to the right slope to return to the village.

Thao held the star anise branch, her hands trembling. That night, she took out her notebook, did not write “historical research” but wrote another line: The slope does not live by printed words, it lives by small footsteps that know how to be silent when passing by the place where people once lay down.

A week after the old trumpet was found, Na Lam village held a ceremony without loudspeakers and no one spoke. Early in the morning, a dozen people in the village, the elderly, a few young people, children and Thao went up La Tham slope. They brought a flat stone taken from the stream bank. The stone surface was slightly inclined, enough to collect dew drops every morning. An indigo scarf covered it temporarily. The trumpet lay on a large stone slab. Thao brought a small carving knife. When the scarf was removed, she bent down, placed her hand on the cool stone surface, and carved each word, slowly, evenly, without looking back. No one asked her what she would write. Mr. Khuyen just sat on the tree roots, smoking hand-rolled cigarettes. When the last carving was completed, Thao wiped the dust off the stone and took a step back. The sun had just risen above the anise trees, shining obliquely through the canopy, the light flickering as if someone had just lit a fire. On the stone stele, there was only one line: Someone once stepped back here so that today I can step forward.

No one said anything. The children bowed their heads. The old woman wrapped her head in a scarf and clasped her hands in prayer towards the slope of La Tham. The forest wind blew gently, the leaves fell sideways as if someone had just retreated over the mountainside.

Source: https://baolangson.vn/con-doc-cu-5062374.html

Comment (0)