Vietnam has climbed the development ladder by daring to innovate. But no path to success is ever the same. What was once a “miracle drug” during the initial take-off phase can now become a barrier if left unchanged. The next step, therefore, requires not only the courage of 1986, but also a new institutional vision so that the economy can not only grow but also develop sustainably, equitably and adaptably in a changing world.

Dr. Vu Hoang Linh received his PhD in Applied Economics from the University of Minnesota (USA) in 2008 and is currently a lecturer at the University of Economics - Vietnam National University, Hanoi. He has many years of experience working at the World Bank, consulting and doing research for many domestic and foreign organizations in development economics, applied microeconomics, etc.

If the first Doi Moi initiated the transition from planning to a market economy, the current period requires a more difficult transition: from factor-based growth to institutional and productivity-based growth…

The 14th National Party Congress, scheduled to be held in early 2026, is expected to be a reform milestone similar to the 1986 Doi Moi.

Exactly 40 years, the coincidence of time has symbolic meaning, but more importantly, this is the moment when Vietnam needs to re-establish its institutional vision for the next 20 years - to realize the aspiration of becoming a high-income country by 2045, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the country's founding.

Renovation 1986: Economic reform goes hand in hand with institutional reform

The decision to comprehensively reform at the 6th Congress in 1986 not only initiated a policy program, but first and foremost a revolution in thinking. After decades of maintaining a centralized planning model, the Vietnamese economy fell into a state of stagnation, hyperinflation, severe shortages of food, goods and social trust.

In that context, the Communist Party of Vietnam demonstrated political courage in acknowledging the limitations of the old model and shifting to a multi-sector commodity economy operating under a market mechanism under state management.

This is a profound shift in thinking: from voluntarism to pragmatism, from denying the market to accepting it as a driving force for efficient resource allocation, and from considering the private sector as an object of reform to considering it as a legitimate and necessary subject of development.

On the basis of new thinking, a series of economic institutional reforms were strongly implemented in the following years.

The impact of these reforms was far-reaching. In just one year, Vietnam went from being a rice importer to the world’s third largest rice exporter. The abolition of subsidies ended decades of rationing.

State-owned enterprises began to operate according to the principle of profit and loss accounting, and were autonomous in production and business. Along with that, the private economy was legalized by the Law on Companies and the Law on Private Enterprises in 1990, thousands of private enterprises were established, operating in the fields of trade, services, and production, becoming a dynamic supplementary force for the economy.

Vietnam also gradually broke the foreign blockade, starting with the promulgation of the Foreign Investment Law in 1987 - a bold step, allowing foreign enterprises to invest directly in the form of joint ventures or 100% foreign capital. From here, FDI became an important capital flow in infrastructure development, processing industry and job creation.

Along with diplomatic efforts, from normalizing relations with China (1991), to establishing diplomatic relations with South Korea, the EU, and especially the United States (1995), Vietnam officially entered a period of integration.

Joining ASEAN in 1995 not only had regional significance but also reaffirmed Vietnam's responsible membership in the international community.

Vietnam's economy grew at an average of 8.2% per year between 1991 and 1995, an outstanding figure in the post-Cold War Asia region. Inflation was reduced from triple digits in the late 1980s to below 15% in 1995, marking a major success in macroeconomic stability.

Agriculture is not only sufficient to feed the rapidly growing population but also to expand internationally. Industry, although still dominated by state-owned enterprises, has begun to show positive changes. In particular, the private sector and the informal economy have become the main source of employment for the majority of the urban and rural population.

Institutionally, the 1992 Constitution marked an important step forward: for the first time, it recognized the private economy, property rights, and legal equality among economic sectors.

This transformation is not simply "unleashing" but a process of re-establishing the economic and legal order in a market-oriented direction, laying the foundation for the model of "socialist-oriented market economy" formalized at the 7th and 8th Congresses.

If we consider Renovation as an "institutional transformation", then this period is the opening chapter.

Towards comprehensive institutional reform 2025 - 2030:

Four decades after the 1986 Doi Moi reforms, Vietnam has made great strides, becoming a dynamically developing economy with per capita income increasing more than 25 times compared to 1990. However, this development process is facing new limits.

Reality shows that the driving forces that brought success in the early stages - such as cheap labor, golden population, FDI capital flows and resource exports - are gradually depleting or losing their competitive advantage. Vietnam currently has more than 100 million people, with about 67% of them of working age, but the birth rate is falling rapidly and the population is aging rapidly.

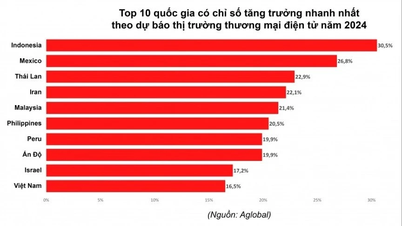

Forecasts show that Vietnam’s golden population period will end around 2042, leading to fiscal pressure, social security and a shortage of skilled labor. Labor productivity, although increasing by an average of 5.8% per year in the period 2016 - 2020, is still significantly lower than that of East Asian countries: in 2020, Vietnam’s productivity was only about 36% of China’s, 24% of Malaysia’s and less than 8% of South Korea’s.

Meanwhile, the FDI sector - although still the main growth driver - has a low localization rate and limited capacity to connect with domestic enterprises. Most of the added value is still outside the border, reflecting the weak technology absorption capacity of the economy.

At the same time, the business environment still faces many institutional barriers. The legal system is unstable, constantly changing and overlapping between laws such as Investment, Land, Construction, and Housing.

The fact that an investment project needs to go through more than 30 types of sub-licenses, issued by many different agencies, is a manifestation of a "fragmented institutional situation", where power is divided but not effectively checked. Petty corruption remains widespread at the grassroots level, while monitoring institutions - both internal and social - are weak and lack independence.

All of this makes businesses afraid of policy risks, hesitant to make long-term investments, and erodes confidence in reform commitments. In that context, without a strong enough institutional reform to unleash endogenous momentum, the achievements of the previous Doi Moi are likely to stagnate or fall into a cycle of "low growth - half-hearted reform - eroded confidence".

The question is: what will be the driving force for development in the 2025 - 2045 period, if Vietnam wants to achieve the goal of becoming a high-income country by 2045, as defined in the Party and Government documents?

The answer - unequivocally: institutional reform must become the central lever. If the Doi Moi launched in 1986 mainly focused on "unleashing" the economy, today's reform requires the creation of a modern institutional system that promotes creativity, transparency, and ensures real equality among subjects.

Vietnam has been showing positive signs. Resolution 19-NQ/TW of 2022 on perfecting the socialist-oriented market economic institution is considered the most comprehensive and incisive document ever in the field of economic institutional reform.

Programs on digital transformation, innovation and urban governance also open up new paths. However, as long as there is no political commitment at the highest level for a strategic and synchronous institutional reform program, these movements will remain localized, fragmented and not enough to create breakthroughs.

The 14th Party Congress - the aspiration to rise up

The first Renovation in 1986 was a "liberation" of economic thinking and institutions, so the second Renovation needs to be a profound institutional reform, aiming to modernize the national governance model.

A comprehensive institutional reform program needs to be put on the highest political agenda at the 14th Congress. This is not just a technical need of public policy, but a political choice that will guide the country for the next 20 years.

Innovation 2.0 needs a vision that is shaped right from the documents of the 14th National Congress, with clear goals, specific implementation deadlines and accompanying policy roadmaps. Vietnam does not lack development motivation - but rather lacks mechanisms for that motivation to be properly promoted.

The 14th Congress is an opportunity to reset the institutional structure to match the stature of a country aiming for high-income status by 2045. As the history of Doi Moi 1986 has proven: when choosing the right time to act, even a country can change its destiny.

The biggest barriers today are no longer physical resources, but the ability to design and operate a modern system of governance – where power is controlled, responsibilities are clearly defined, and results are the ultimate measure of policy.

The new demands of an innovative, digital, low-carbon, globally connected economy require a completely different institutional ecosystem: more flexible, more transparent, and capable of faster policy responses.

International experience - from Korea, China, Singapore - shows that: breakthrough institutional reforms are often initiated when a country faces a new development threshold, where "institutional boosts" become a necessary condition to move forward.

In an uncertain and competitive global context, institutions will determine not only the rate of growth, but also the quality of development and the ability to integrate.

It is time for senior leaders, the administrative apparatus, and the business community to unite in the view that Vietnam needs a new breakthrough mindset - institutional mindset, transparent mindset, and long-term creative mindset. In pivotal moments, it is this mindset - not financial resources or technology - that determines the country's long-term prosperity.

Three axes of reform should be on the agenda:

- Urban government institutions and decentralization to localities. From July 1, 2025, Vietnam will officially operate a two-level local government model (provincial and communal levels), completely replacing the previous three-level structure after abolishing the district level according to the Law on Organization of Local Government (amended) passed by the National Assembly on June 1, 2025.

Despite its standardization and modernization, the current decentralization mechanism still does not properly reflect the capacity and distinct roles of leading localities such as Ho Chi Minh City or Da Nang.

These cities need to receive real budgetary empowerment, flexibility in planning - investment - personnel organization, and at the same time be clearly accountable through a mechanism for monitoring results, including public evaluation, reporting on output efficiency, monitoring by political - social organizations and the media.

- Institutions to control power in the Party and State. Although there has been much progress in preventing high-level corruption, power control is still administrative - not based on modern institutional principles.

The 14th Congress should lay the foundation for a substantive power control architecture, including mechanisms: internal Party supervision through a more independent instrument of the Inspection Commission; administrative supervision through inspection agencies; and social supervision through the press, elected representatives and intermediate institutions. Gradually professionalize legislative, auditing and statistical agencies - and give these agencies more power to operate with technical independence.

- Perfecting modern market institutions. This requires addressing "bottlenecks" in asset ownership (especially land), public asset valuation, fair competition, and breaking administrative monopolies in licensing, bidding, and investment approval. The adoption of a new Land Law, amendments to the Bidding Law, the Budget Law, and the promulgation of a law on the right to access public information should be integrated into an institutional reform package.

Three major requirements for the current system

The need for a modern rule of law State, where executive power is transparent, the legislature is professionalized and the judiciary is truly independent. The judiciary must be an impartial arbiter, not only to protect property rights, but also to encourage investment and innovation.

Effective and transparent power control mechanism. The solution cannot rely solely on inspection, examination or handling of behavior, but must build a mechanism to redesign power towards controlled decentralization, combined with independent monitoring tools such as the press, civil society and digital technology.

Building a complete and integrated market institution: the domestic private sector is treated equally, has access to resources (land, capital, information) publicly and competitively.

The public policy system needs to shift from direct intervention to a principle-based legal framework to create an equal environment instead of conditional incentives. At the same time, continue to promote reforms in areas that are still "privileged" such as land, public finance and public services.

Ho Chi Minh City needs real decentralization

After the merger, Ho Chi Minh City is expected to contribute about 32% of the country's GDP and nearly 30% of domestic budget revenue, but its ability to make decisions on public investment, planning and finance is very limited. The 2015 State Budget Law stipulates that Ho Chi Minh City's budget is a provincial budget, requiring central approval for most major projects, including ODA.

A specific example: Metro Line No. 1 Ben Thanh - Suoi Tien started construction in 2012 but was delayed many times due to having to request adjustments to the total investment from the Ministry of Planning and Investment and the Ministry of Finance, even though the city was the investor.

Similarly, Ho Chi Minh City’s retained budget is about 21%, significantly lower than Hanoi (32%) or compared to large cities in countries with decentralized models. Meanwhile, urban infrastructure, public transport, and canal renovation are all seriously overloaded.

The situation in Ho Chi Minh City clearly reflects the need for real decentralization in a special urban governance institution - where local authorities need fiscal, planning and investment space commensurate with their leading role.

Source: https://tuoitre.vn/thoi-khac-ban-le-cho-doi-moi-2-0-20250826152907789.htm

![[Photo] Ho Chi Minh City is filled with flags and flowers on the eve of National Day September 2](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/1/f493a66401844d4c90919b65741ec639)

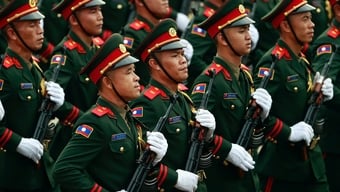

![[Photo] People eagerly wait all night for the parade on the morning of September 2](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/1/0cf8423e8a4e454094f0bace35c9a392)

![[Photo] General Secretary receives heads of political party delegations from countries attending the 80th anniversary of our country's National Day](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/1/ad0cb56026294afcae85480562c2e790)

![[Photo] Celebration of the 65th Anniversary of the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between Vietnam and Cuba](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/1/0ed159f3f19344e497ab652956b15cca)

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man receives Cambodian Senate President Hun Sen](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/1/7a90c9b1c1484321bbb0fadceef6559b)

Comment (0)