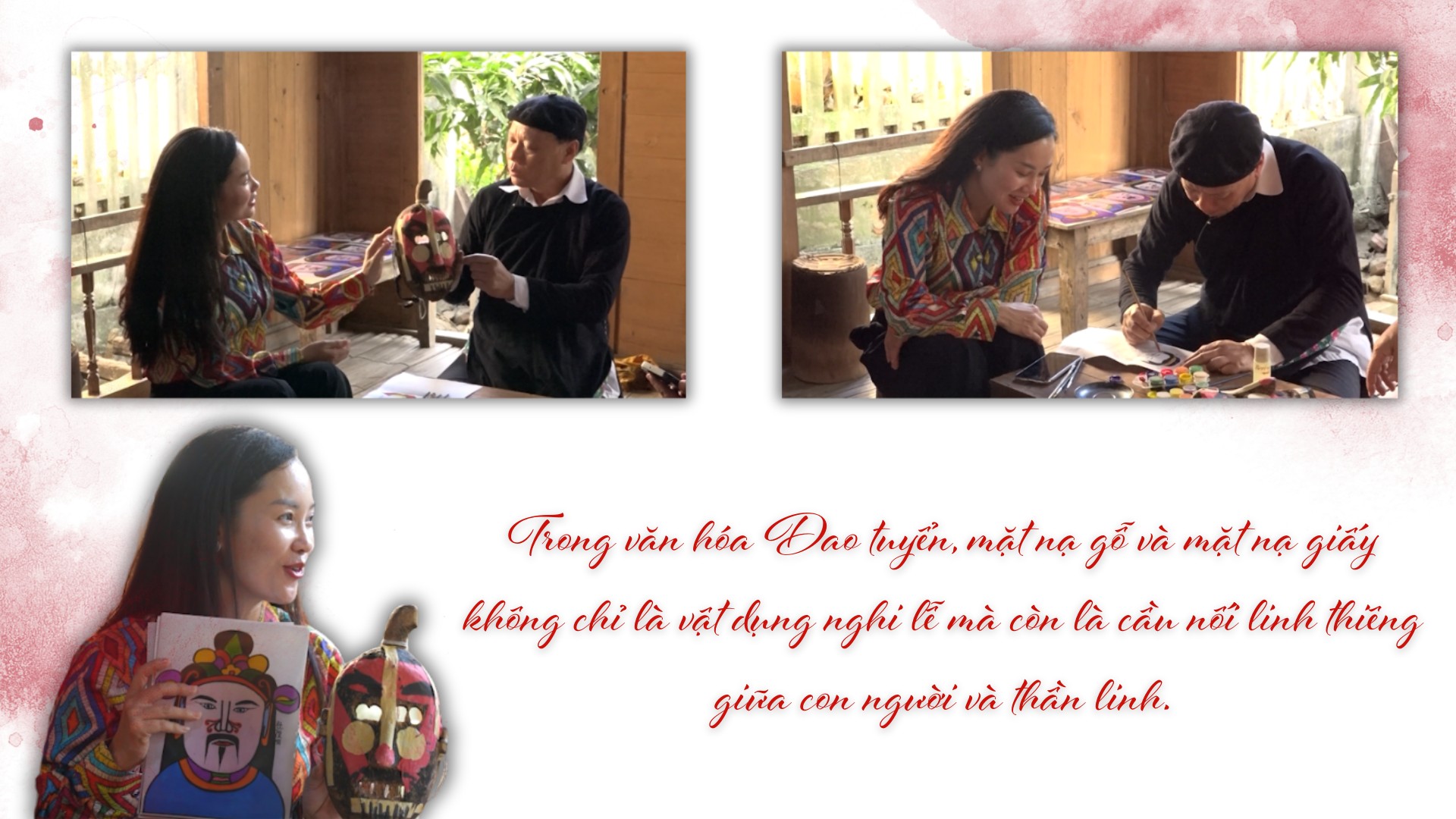

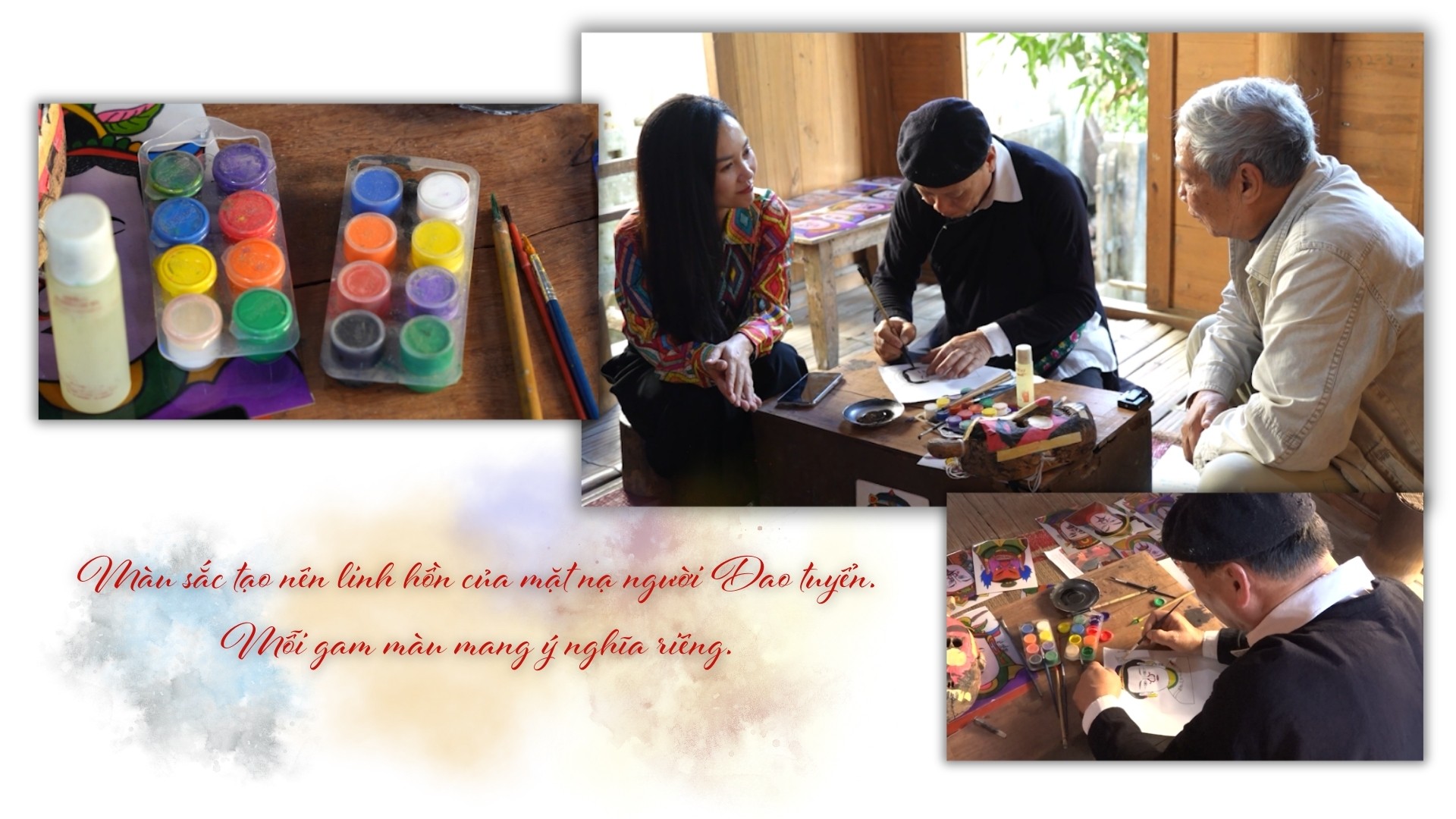

I arrived at Phuc Khanh commune, Lao Cai province on a late autumn day… The last rays of sunlight of the season gently fell on the grass and trees, on the stilt houses in the small village of Na Khem, we met Mr. Ly Xuan Dinh - a man who always carries within himself the pride and responsibility of preserving and passing on the mask making technique of the Dao Tuyen people from 5 generations of the Ly family. Mr. Dinh smiled and waited for us at the table with many colors and countless drawings of the sacred masks in the religious life of the Dao Tuyen people here.

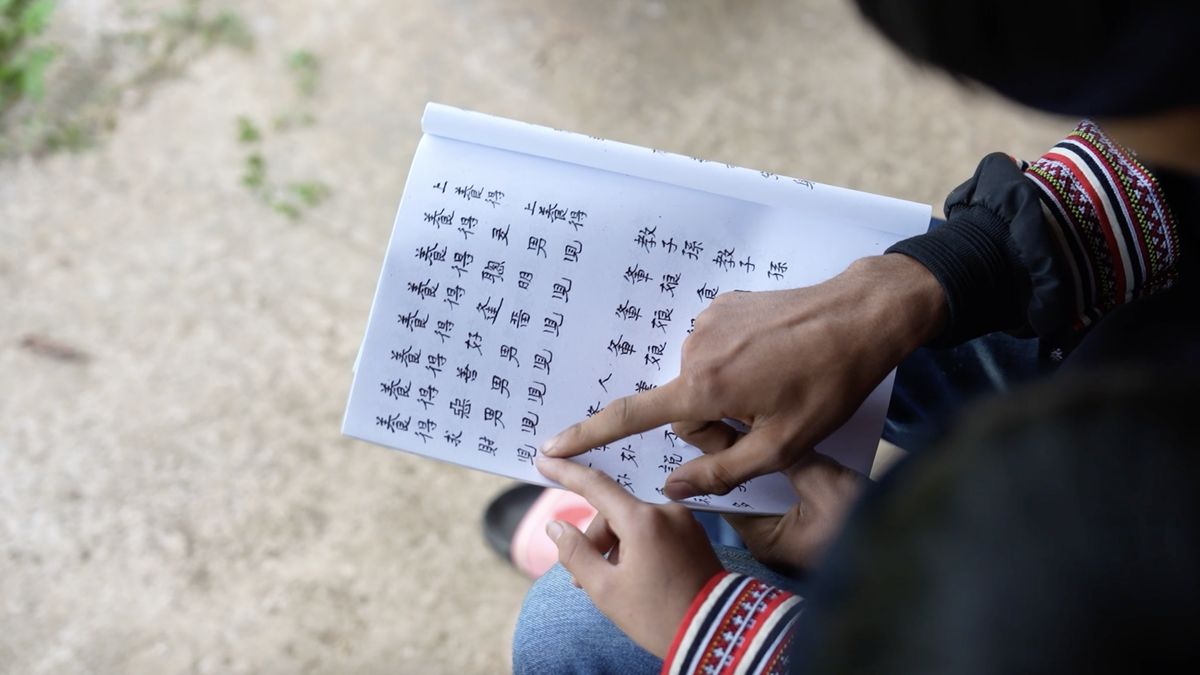

Looking at Mr. Ly Xuan Dinh’s hands, which have become calloused over the years, gently touching each carving, each grain of wood, each drawing, each color, it seems to be awakening the sleeping soul within. The masks of the Dao Tuyen people, sacred and mysterious, have been attached to many generations of this Phuc Khanh land.

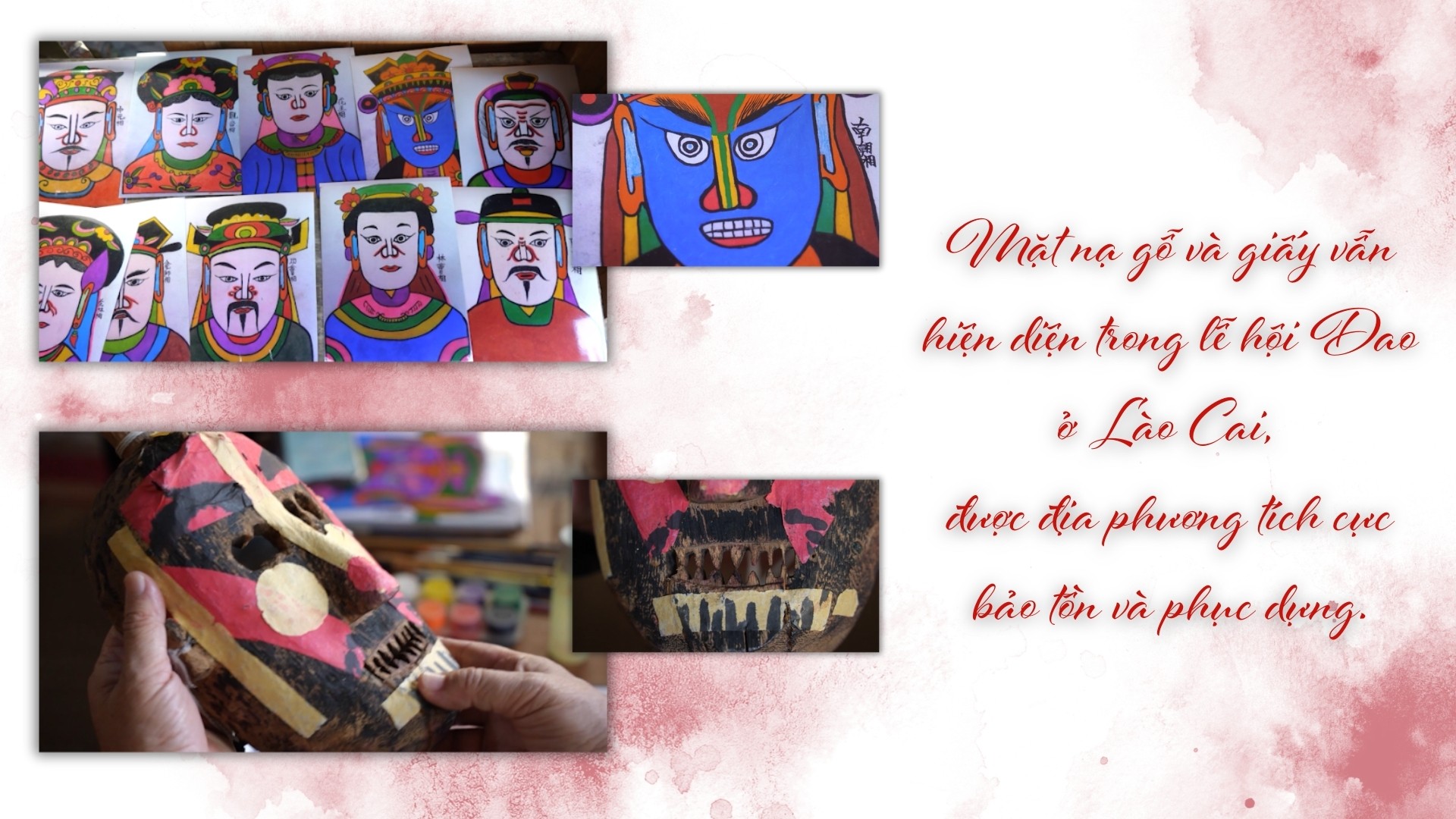

In the culture of the Dao Tuyen people, wooden masks and paper masks are not simply decorative objects or ritual props, but also souls, bridges between humans and gods, between the visible world and the invisible world. Especially in the coming-of-age ceremony - the ceremony of becoming an adult and recognizing a Dao Tuyen man as qualified to be a shaman, or in the vegetarian ceremony - the ceremony to send the soul of the deceased back to the ancestors, masks are indispensable objects.

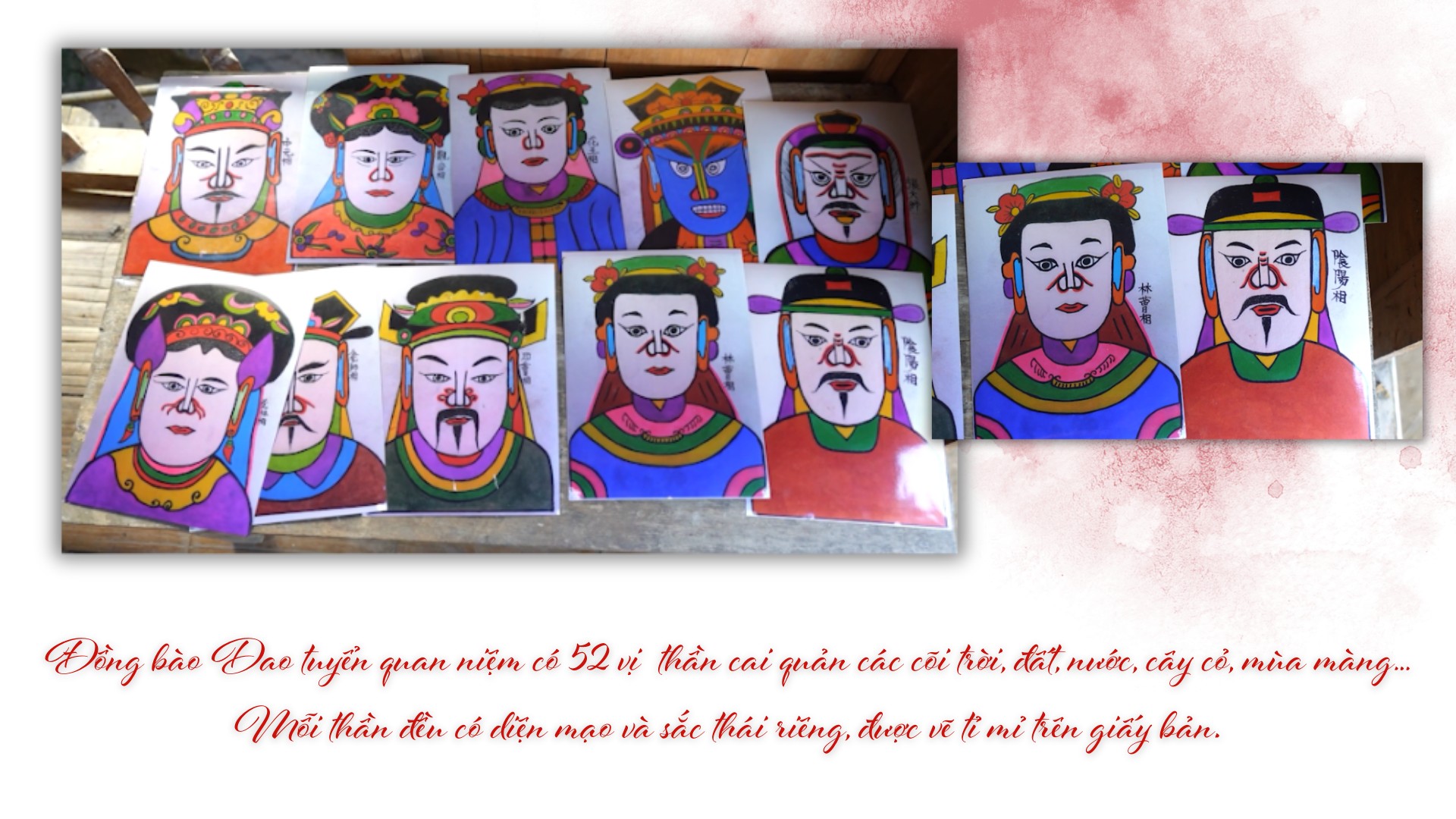

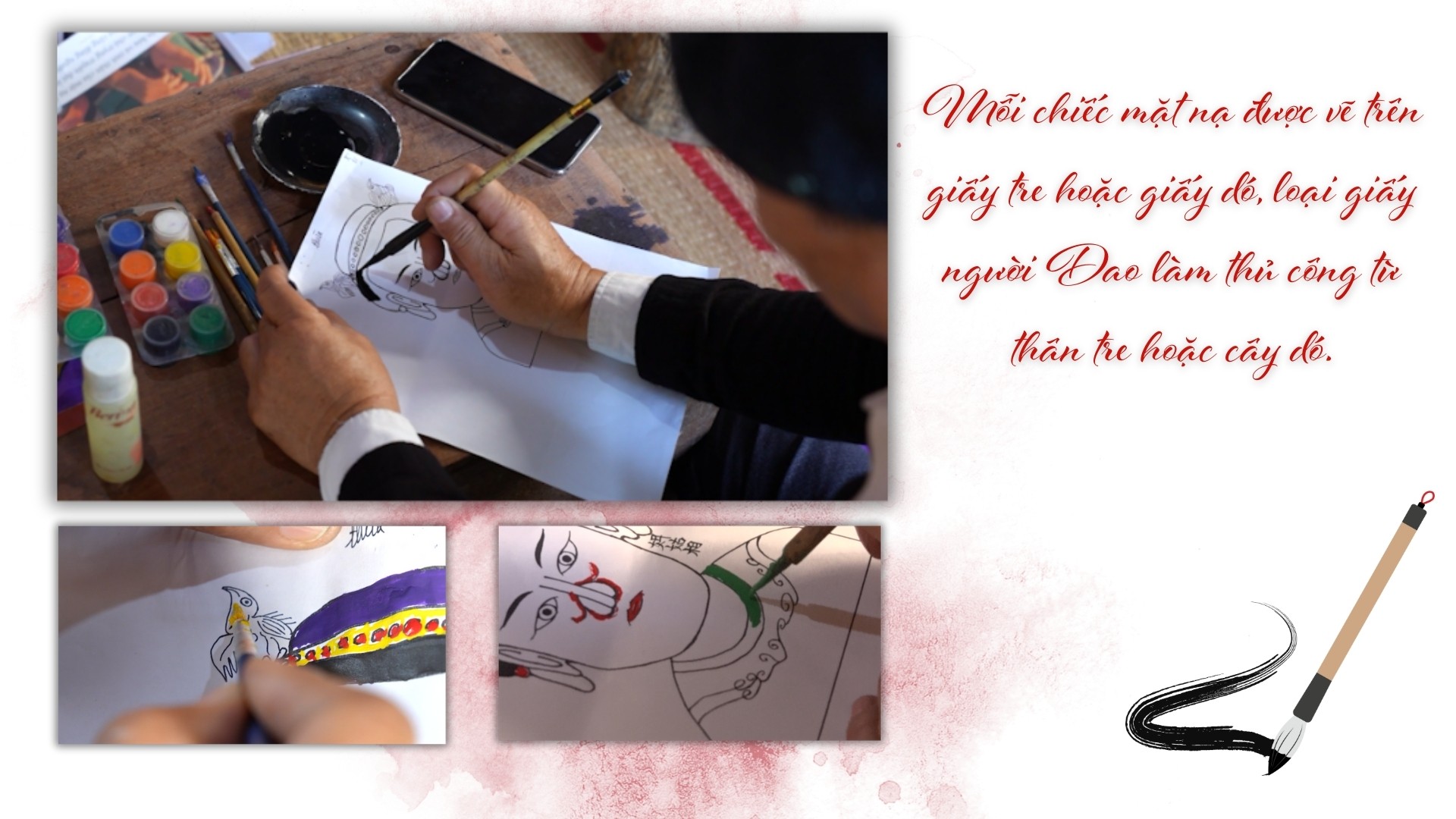

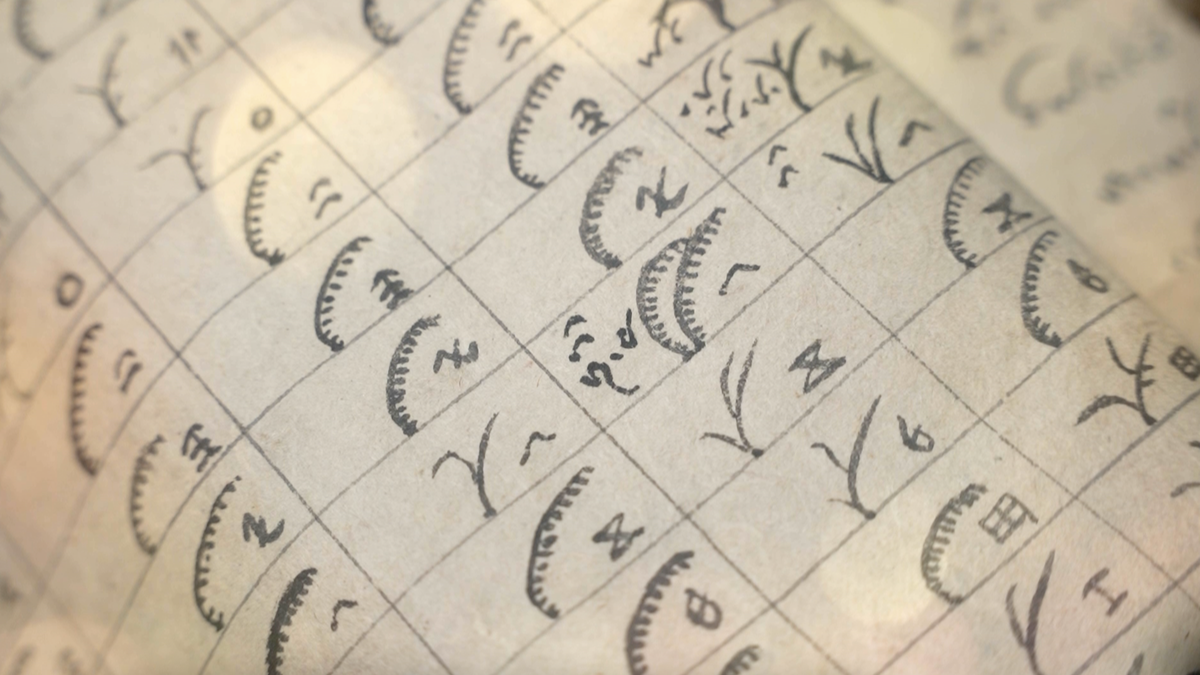

Each mask is the embodiment of a god who protects the village. According to ancient beliefs, the Dao Tuyen people have up to 52 gods, who govern the realms: sky, earth, water, trees, grass, crops... Each god has its own face and expression, elaborately drawn on ban paper - also known as bamboo paper or do paper (a type of paper handmade by the Dao people from bamboo or do tree trunks). From the silent god of the earth, the majestic god of water, to the gentle midwife or the fierce king of the forest - all come from the talented hands and respectful hearts of artisans like Mr. Dinh.

Wood, paper and ink are the selection of heaven and earth… In the traditional wooden house of the Dao people, the smell of fig wood, paper and ink mixed with kitchen smoke, warm and intimate.

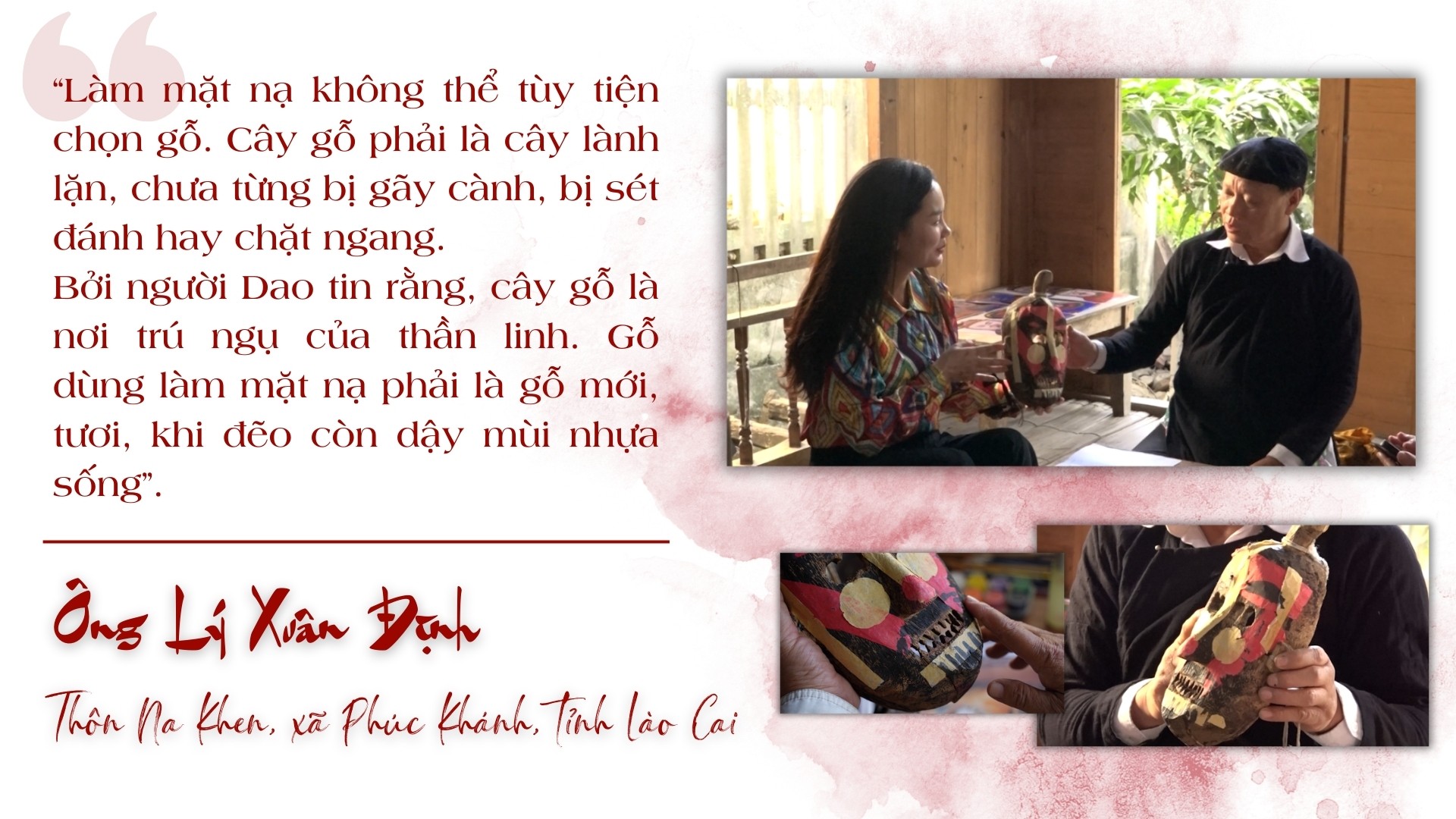

Mr. Ly Xuan Dinh slowly said: “To make a mask, you cannot choose wood randomly. The tree must be intact, never broken, struck by lightning or cut in half. Because the Dao people believe that trees are the dwelling place of gods. The wood used to make the mask must be new, fresh, and when carved, still has the smell of sap.” Sung wood is the most chosen type - light, spongy, easy to carve. The sung tree also symbolizes fertility and growth, symbolizing fortune.

After shaping, the mask is naturally dried, waiting for an “auspicious day” to “consecrate” the wood, officially turning it into a sacred object. This is usually done during vegetarian or ordination ceremonies, when the shaman recites a spell, beats the drum, and invites the spirit to enter the mask.

Besides shape, color is the element that creates the soul of the Dao Tuyen mask. Each color has its own symbol: red is power and fire, yellow is light and prosperity, green is mountains and forests, life, and white is the underworld and purity.

Mr. Dinh said that when drawing masks, the shaman must clearly understand each layer of meaning. A single wrong color stroke can distort the sacredness of the ritual. The completed masks often have a fierce appearance - wide eyes, bared teeth, wide open mouth, hair flowing down like a black stream. But hidden under that "creepy" appearance is a strong belief: the ferocity is to ward off evil spirits, to protect the peace of the villagers, for a bountiful harvest, for the souls of the deceased to be liberated.

This year, over sixty years old, Mr. Ly Xuan Dinh still maintains the flame of cultural preservation - working as a shaman in the Dao Tuyen village... Therefore, Mr. Dinh is one of the few Dao Tuyen people in Phuc Khanh who know how to make wooden masks and paint paper masks, which have been passed down from father to son, and Mr. Dinh is the fifth generation.

Currently, Mr. Dinh still owns the wooden mask used in the Dao Tuyen's initiation ceremony - passed down from his ancestors. Every time he touches the cracked, time-stained wooden mask, he seems to hear the whispering of the mountains and forests, and the teachings of his ancestors.

“I maintain the profession of painting and making masks not to sell. I do it to preserve the Dao Tuyen’s tradition, so that future generations will know how to perform the ceremony properly. The mask is not just an object, but a story of the family, of beliefs” - as he spoke, Mr. Dinh’s eyes seemed to light up in the hazy smoke from the kitchen.

Now, Mr. Dinh’s son and grandson are also learning the craft - following in their father’s footsteps in making wooden masks and painting paper masks of the Dao Tuyen people. Young people in the village, even in other communes such as Bac Ha, Sa Pa, Bao Thang, often come to his house, not only to see him paint masks, but also to hear him talk about the gods, about the songs and dances in ancient rituals…

During our trip to Phuc Khanh, we met artist Khuc Quoc An - a son of Hanoi , who has spent nearly 20 years researching the culture of ethnic minorities in the highlands, especially the Dao people in Lao Cai, and he seems to have found the "soul" in wooden, bamboo bone and papier-mâché masks.

Painter Khuc Quoc An - a native of Hanoi, has spent nearly 20 years researching the culture of ethnic minorities in the highlands, especially the Dao people in Lao Cai - said that the first time he saw a Dao mask, he was overwhelmed by the powerful energy emanating from those seemingly rough lines.

“It is a primitive work of art, with profound philosophy. Each block of wood, each color, each carving contains the worldview and philosophy of the Dao people. The beauty here is not perfection, but the soul, the vitality of belief.”

Over the years, artist Khuc Quoc An has traveled to several ethnic minority areas in Lao Cai to study ancient masks and traditional color combinations to incorporate cultural heritage into modern paintings. For him, these masks are not only the heritage of an ethnic group, but also a source of inspiration for contemporary Vietnamese art.

The techniques of making wooden masks and painting paper masks still exist in the cultural life of the Dao ethnic group in Lao Cai through festival seasons, through the sound of drums and trumpets echoing in the mountains and forests. In particular, in recent years, the local government and the Lao Cai cultural sector have made great efforts in collecting, preserving and restoring Dao rituals. The Cap Sac and Then rituals have been organized with the participation of artisans and local people.

Cultural and tourism programs have gradually made wooden masks and paper masks of the Dao people a highlight in cultural exploration programs, helping tourists better understand the spiritual world of the highland people.

Interestingly, some artisans and painters have incorporated mask images into works of art, from paintings, sculptures to decorative designs, creating a “new language” between tradition and modernity.

Painter Khuc Quoc An said: “Dao masks should not be considered as objects for worship but as aesthetic heritage and cultural symbols. When properly respected, the masks can enter contemporary life without losing their souls.”

For Mr. Ly Xuan Dinh, this is even more meaningful. Because for him, a young person coming to learn a trade, or a tourist coming to hear stories about the gods, is also a way to inspire.

“I just hope my children and grandchildren know that behind the wooden faces and paper masks are stories of our ancestors, of the land and forests, of our Dao people. If we don’t teach them, the masks will only be in display cases in museums,” Mr. Dinh worries.

In the late autumn afternoon, pale yellow sunlight covered the roof of Mr. Ly Xuan Dinh's house. A wooden mask passed down through 5 generations hung quietly on the wall, 52 paper masks of various colors and expressions... In that space, the "keeper of the fire" of the culture of the Dao Tuyen ethnic group was still diligently researching and passing on mask-making techniques, softly humming an ancient melody: "Oh forest, please keep my soul. Keep the sound of drums, gongs, keep the masks of our ancestors..." as if to affirm that - no matter how time passes, the Dao masks will continue to tell the story of the origin, the enduring vitality of a nation that knows how to carve its "soul" into every grain of wood, every sacred drawing.

Presented by: Bich Hue

Source: https://baolaocai.vn/nhung-chiec-mat-na-ke-chuyen-di-san-post887470.html

![[Photo] Dan Mountain Ginseng, a precious gift from nature to Kinh Bac land](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F11%2F30%2F1764493588163_ndo_br_anh-longform-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)