Until April, the Iran-Israel war had been fought in the shadows. Iran decided to bring the war into the light by openly attacking Israel directly from its own territory. Some observers said that Iran’s drone and missile attack on Israel on April 13 was a symbolic act. However, given the number of drones and missiles used and the amount of explosives they carried, it was clear that Iran intended to cause serious damage.

Israel's unprecedented action

Israel’s defenses were nearly flawless, but they did not repel the Iranian attack on their own. Like the Iranian attack, direct military intervention by the United States and several allies, including Arab states, was unprecedented. The U.S. Central Command, with the participation of the United Kingdom and Jordan, intercepted at least a third of the Iranian drones and cruise missiles aimed at Israel; Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates also shared intelligence to help Israel defend itself. The willingness of all sides to take on this role is remarkable, given the lack of Arab public support for Israel’s war with Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

Five days later, in response to the Iranian attack, Israel took into account US calls for restraint and fired only three missiles at the radar base that guides the S-300 missile defense battery in Isfahan, which houses Iran’s uranium conversion plant. This was a very limited response, designed to avoid casualties but still demonstrated that Israel could penetrate Iran’s defenses and strike any target. Israel appears to have realized that the best way to deal with the threat posed by Iran and its proxies was to work with a coalition—which was also unprecedented.

Now, as Israel faces not only Iran but also its proxies, the cost of fighting on all fronts on its own is becoming too high. This development, coupled with the Arab states’ willingness to join Israel in confronting the threat posed by Iran and its proxies in April, suggests that the opportunity has opened up for a regional coalition pursuing a common strategy against Iran and its proxies.

In terms of defense strategy, Israel has long been committed to self-reliance. Tel Aviv only asks the United States to ensure it provides financial resources. However, the help Israel receives to defend itself against Iranian attacks may be not only welcome but necessary.

This support imposes obligations on Israel. When other countries defend Israel, they have the right to expect Israel to take their interests and concerns into account. After the Iranian attack, President Biden made it clear to Israeli leaders that they did not need to respond because their successful defense was a major victory and a defeat for Iran. For Israel, not responding contradicts its fundamental concept of deterrence.

Israel’s deterrence concept has always shaped its response to direct threats, with one notable exception in the current context. During the 1991 Gulf War, the night after US forces invaded Iraq, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein ordered a Scud missile attack on Israel. Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Arens and other senior officers wanted to respond.

However, the then-US President George HW Bush administration, and in particular US Secretary of State James Baker, persuaded Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir not to do so. Secretary Baker assured Prime Minister Shamir that Israel could give the US the exact targets it wanted to attack and the US would attack those targets. However, he also stressed that the whole world was against Saddam and that a direct Israeli response would risk breaking the anti-Iraq coalition.

The problem of unilateral ceasefire

The nature of Israel’s response to the Iranian attack suggests that Prime Minister Netanyahu is also willing to take into account US concerns. Now, Netanyahu is under pressure to “heal the rift” with the US president. It is not a rift over the fundamental objective of Israel’s war in Gaza—ensuring that Hamas can never threaten Israel again—but over Israel’s approach to the military campaign and humanitarian aid to Gaza.

As in 1991, Israel’s restraint in response to an outside attack will not reset its relationship with the United States. Before Israel attacked Rafah, relations between Biden and Netanyahu were likely more strained. But a normalization agreement between Israel and Saudi Arabia is the most important thing that could change the trajectory of that relationship.

President Biden understands that because Saudi Arabia requires credible political progress on the Palestinian issue to complete a normalization deal, Netanyahu will have to confront the most staunch political supporters who oppose a Palestinian state. And negotiations cannot truly move forward without the humanitarian crisis in Gaza easing.

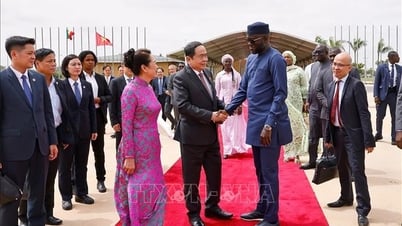

|

| A ceasefire in the Gaza Strip, if achieved, would be a precious moment of peace for the parties involved to consider the next steps to cool down the conflict. Photo: Reuters |

Such a move would certainly be politically difficult for Netanyahu. He could argue that a temporary ceasefire would relieve Hamas of military pressure. However, after significantly reducing its military presence in the Gaza Strip by November 2023, Israel would not be able to exert the same military pressure on Hamas as it did when the hostage deal was negotiated with the help of intermediaries that same November.

Israel’s threat to attack Rafah has increased pressure on Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar in Gaza, but the Rafah operation was thought to be impossible until Netanyahu fulfilled his promise to Biden that no landing would take place before Israel evacuated the 1.4 million Palestinians trapped in the area. Evacuation is not just about getting people out, but also about ensuring they have a place with adequate shelter, food, water and medicine.

Faced with this reality, Israel was told to do something it really did not want to do. If it could not enter Rafah, then a ceasefire would mean giving up almost nothing and gaining a lot.

A four to six week ceasefire would give international organizations a chance to defuse the situation in Gaza and address the global famine concern. They could establish better mechanisms to ensure that humanitarian aid not only reaches Gaza but also reaches those most in need.

A ceasefire would draw global attention to Hamas’s intransigence and the plight of Israeli hostages. It would also help change the dubious global narrative about Israel and reduce pressure on it to end hostilities unconditionally.

Simply put, a unilateral Israeli ceasefire for four to six weeks would create a strategic opportunity – especially if it created an opportunity to normalize relations with Saudi Arabia and make the implicit regional alignment that emerged after Iran’s attack on Israel more tangible.

Source: https://congthuong.vn/loi-thoat-nao-cho-xung-dot-o-dai-gaza-israel-co-nen-don-phuong-ngung-ban-326027.html

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs the second meeting of the Steering Committee on private economic development.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/01/1762006716873_dsc-9145-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)