Three-quarters of the world's wild tigers live in India, but destruction of their natural habitat has caused their numbers to plummet. The number of tigers roaming the country's forests fell from 40,000 when India gained independence in 1947 to just 1,500 in 2006.

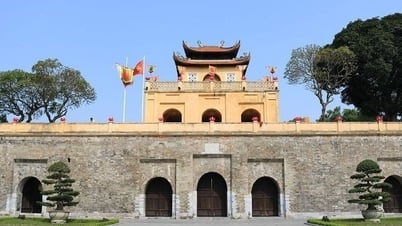

Tiger stripes are unique, like human fingerprints. There are an estimated 4,500 left in the wild across Asia. Photo: AFP

However, their numbers have risen above 3,000 this year, according to the latest official figures. To help their numbers recover, India has designated 52 tiger reserves where logging and deforestation are strictly controlled.

Tigers are an "umbrella species," Aakash Lamba, a researcher at the National University of Singapore and lead author of the new study, told AFP.

“This means that by protecting them, we also protect the forests they live in, which are home to an incredible diversity of wildlife,” he told AFP.

Forests are a "carbon sink," meaning they absorb more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than they release, making them an important tool in the fight against climate change.

India, the world's third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, has pledged to reduce its emissions.

Lamba, who grew up in India, said the team of researchers sought to establish an empirical link between tiger conservation and carbon emissions.

They compared deforestation rates in special tiger reserves with areas where tigers also live but are less strictly protected.

According to the study, more than 61,000 hectares of forest were lost across 162 different areas between 2001 and 2020. More than three-quarters of the deforestation occurred in areas outside tiger reserves.

Within tiger reserves, nearly 6,000 hectares were saved from deforestation between 2007 and 2020. That equates to more than a million tonnes of carbon emissions absorbed.

“This important result highlights how investing in wildlife conservation not only protects ecosystems and wildlife, but also benefits societies and economies ,” said Lamba.

The research, published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, comes after a study published in March suggested protecting or restoring a handful of wildlife species such as whales, wolves and otters could help capture 6.4 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide each year.

Mai Anh (according to AFP, CNA)

Source

Comment (0)