The objectives and missions of these two reporting trips are different. If in the 2010 World Cup, I reflected on a game, a sports match, then in the trip to Myanmar, I had to record a natural disaster: an earthquake. Both of these events are similar in that they are historical moments that only happen once in a lifetime.

However, thinking back, we were always safe while reporting on the earthquake in Myanmar, a place that seemed extremely dangerous. Meanwhile, it sounds hard to believe, but I had to face the moment of life while reporting at the 2010 World Cup.

I still remember clearly, it was the day of the 2010 World Cup Final. I happened to be standing in the stands cheering for the Spanish team. When their team won the championship, the audience cheered in joy of victory. In that excitement, the fans celebrated, rushing forward. One person pushed another. And foreigners were very tall, while I was only over… 1m50 tall, tiny and lost in the crowd.

Journalist Thanh Van in the stands of World Cup 2010.

So I was stuck in the middle of the crowd. It felt like I couldn’t walk anymore. At that moment, I just tried to find a way to lift my head up to the sky and breathe. After being swept along by the crowd for a while, I reached the wall of the stadium. Immediately, I asked a foreign friend to carry me to the wall. Without that help, I would have continued to be pushed along the crowded crowd and fallen into a state of suffocation, almost dying…

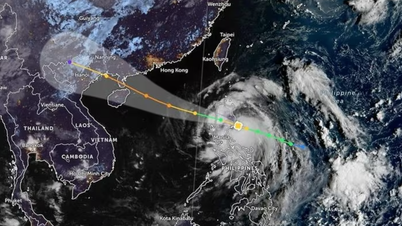

During our reporting trip to Myanmar, everyone was cautious about the aftershocks of the earthquake as danger lurked at any moment. Fortunately, we completed the trip smoothly and safely.

And all such business trips were urgent and in a short period of time. We almost did not have much time to prepare. From the time we received the mission, until we set off and heard the announcements, instructions and prepared all our luggage, it took less than a day for us to arrive at Noi Bai airport.

While at Noi Bai airport, I received information that the Vietnamese rescue team would stop in Naypyidaw, the capital of Myanmar. But the epicenter of the earthquake was in Mandalay, a city more than 30km away from the capital.

Immediately, I made some calculations while at the airport. Our team was leaving for Myanmar with four members. I quickly asked for the leader's opinion, as well as agreed with the group to split into two teams. I and a cameraman would stay in Naypyidaw to closely follow all rescue and relief activities, and report on the damage and casualties in the capital. The remaining two reporters would go to the epicenter of Mandalay.

But it must have been luck, everything went quite well for us. On March 31, we left Vietnam, and on April 1, Myanmar declared a ceasefire. At that time, the political situation was relatively safe. In Mandalay, when my colleagues arrived in the city, they reported that there were still earthquake aftershocks. And this made us extremely worried about the crew. I also entrusted them to the people who went with the group, and the brothers were still proactive in the process of working.

Another lucky thing was that we were accompanied by our colleagues from Nhan Dan Newspaper. They were people who had a lot of experience working at hot spots. And they were also divided into two groups like us. Having that companionship also made me feel more secure.

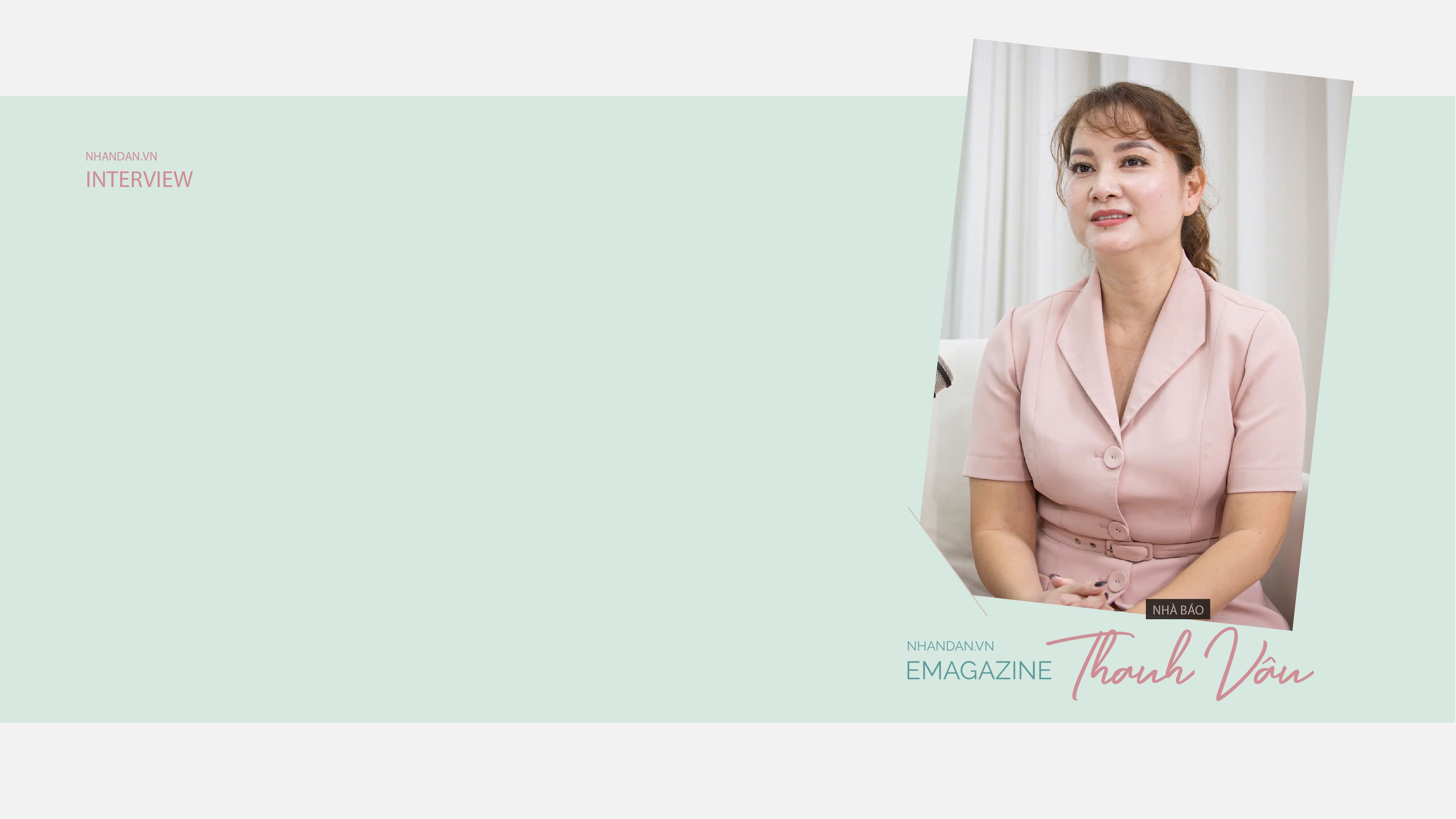

Journalist Thanh Van (right) working in Myanmar during the earthquake disaster in April 2025.

Before leaving, our leader - General Director of Hanoi Radio and Television Nguyen Kim Khiem, a person with rich experience working in disaster and disaster areas, also shared with the working group. Those shares made me feel both more worried and more secure.

What worried me more was that the leader asked the logistics team to prepare important things for the crew. First, a satellite phone. Although Myanmar already had a telecommunications network and the signal was quite stable, he still prepared a satellite phone to be used in case of the highest risk. Second, medicine. We were fully prepared with all kinds of medicine, clearly stating what to use in what circumstances. He also instructed us on small things, such as storing clean water at all costs. This factor is very important when working and staying in disaster areas.

I set off with the mindset of a journalist, a messenger, with the desire to get the most authentic images, without fully imagining the difficulties and dangers. However, I was also more assured because we had been prepared with the most modern working equipment.

The leader also advised: “In the most special cases, I allow you to leave all your equipment behind. Life is the most important thing, you need to keep yourself safe.” Therefore, even though we were going to a place where we knew there would be many unforeseen dangers, even life and death, we felt more secure thanks to the advice to put the safety of reporters first.

"In special cases, you leave all your equipment behind. Life is the most important"

Arriving in Naypyidaw, I contacted a colleague who had been here a day before. He was surprised by my appearance because… women here suffer a lot. No electricity. No water. Living conditions are extremely difficult. I just replied: It’s okay, I’m used to suffering. And that was actually very mild compared to the images of what I might have to face.

Two crews in Naypyidaw and Mandalay were also cut off. When the earthquake struck, the infrastructure collapsed, affecting the transmission lines. The signal was unstable. Sometimes it was there, sometimes it wasn’t. Even now, when we returned from the trip, people still talk about that story, as a lesson we need to learn from for future assignments.

I have to admit that we are living in an era where information technology is very popular and modern. My subjectivity makes me think that we can do everything via the Internet, with just a phone with coverage in hand. We thought that we would not need to use the satellite phone so we did not turn it on when we went to Myanmar.

But the reality was completely different. On the first day of work in the capital Naypyidaw, we missed the early news when the 3G connection had problems. The news and articles had to be moved to the last news of the day. There was not much time, so the next day, everyone had to learn from experience. Wherever we went, whatever we could report, we would send back home. If we were in a place without signal, we would constantly move on the road to catch the signal, carrying our phones and laptops in the car. When we reached a place with signal, we would stop to send the earliest news and articles, serving the broadcast.

And since we were also in Myanmar, we understood that the situation was not too tense and the reason for the disconnection was due to a problem with the transmission line. With my worries for my colleagues, I also waited until the signal was reconnected. Although it was unstable, we also got the information that on the other end, everyone was safe. But the atmosphere at the station was different. Because we could not contact both teams, the anxiety multiplied many times.

Perhaps, this is the place with the most trapped bodies in the capital Naypyidaw. I still remember clearly the feeling when I arrived at the scene. Perhaps, looking at the pictures, what we see is grief and devastation, but it is difficult to imagine what the smell there is like.

My professional instincts made me rush inside to get to work immediately, but the strong smell of death rose up, hitting my nose, making me pause for a moment. After a while, I gradually got used to the smell of death. But there were times when the scent was so strong that it made me dizzy...

Outside the Ottara Thiri hospital, relatives of the victims were always on duty. They waited all night, despite the power outage and lack of light. Even when the rescue team left the night before and returned the next morning to work, they still stood there waiting. Only when their relatives were found, did they begin to perform the rituals according to Myanmar tradition, and then return.

The local people also appreciated and cared for the rescue team and reporters like us. Working under the hot weather, with almost no shade or roof, they lent us small fans. Every day, benefactors also brought water trucks. With that support, we did not need to use the water we had previously stored.

Returning to life in the earthquake zone after working hours. During a week in Myanmar, I only slept about 3 hours a day. During the day, the weather was about 40 degrees. At night, it was even hotter. It was not until the 5th day of the trip that we were able to… take a proper bath. Unfortunately, the water was only available for a certain period of time, and its color was as murky as… boiled water from spinach. Therefore, almost every day, we only used 2 small bottles of water for personal hygiene.

Journalist Thanh Van working in Myanmar, April 2025.

Until the day of return, I kept wondering what motivation and strength made me run like that, working from morning to night. In fact, for the first 2-3 days, I didn’t eat anything, just drank a lot of water, just immersed myself in work and forgot about the fatigue.

I think the biggest motivation that drove me to work during my trip to Myanmar was the passion for my profession. And seeing the Vietnamese soldiers and police officers working hard to carry out rescue work, I felt that my contribution was small.

Some people only know a little. Obviously, journalism requires respect for the truth, and to write about characters, we need to know their stories well in order to convey them. Because of the language barrier, I missed out on 1-2 very good stories during my work.

In daily life, I still understand them, feel their affection for the Vietnamese rescue team and the team of journalists. Sometimes, the concern will erase the language barrier. For example, the grateful eyes, the hope that the rescue team will soon find the trapped people. Those are also actions such as giving water, sitting and fanning the members of the team.

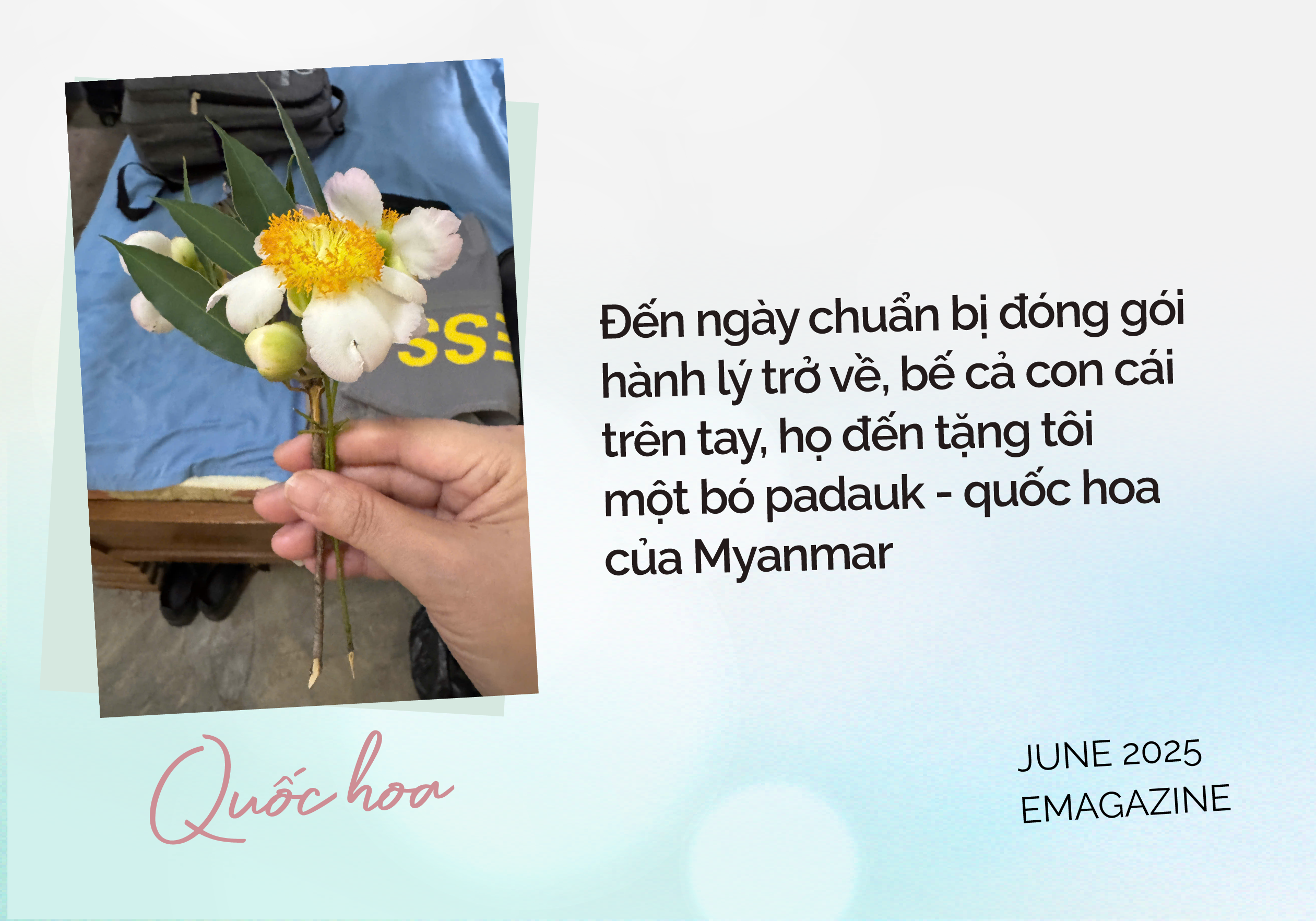

For several days in a row in the rescue area, I was the only woman. The people of Myanmar observed that. When it was time to pack my bags to return home, with their children in their arms, they came to give me a bunch of padauk - the national flower of Myanmar. Even though they spoke in their mother tongue, I still understood what they wanted to express.

As a journalist, I don’t think it’s better to be male or female. Maybe, in terms of health, I can’t carry heavy loads like my male friends. But I believe I have the stamina, strong will and spirit.

I don’t think that women are at a disadvantage when working in disaster areas. On the contrary, I find it advantageous because everyone “loves” me the most in the group. At the end of the reporting trip in Myanmar, I was still impressed by the soldiers’ jokes about me: “The group has 88 men, only this girl is a woman. Yet she dares to go!” If there is a next trip, I will still be the first to volunteer!

Journalist Thanh Van. (Photo: NVCC)

So what do you look for in such volunteering times?

Perhaps it is the passion of the profession. I often share that I really enjoy working at moments that only happen once in a lifetime. For example, the 2010 World Cup was my first time working on the international stage or I participated in working during disasters and natural disasters. For me, those are the marks that I cannot miss. And I realize that by being there, I will be able to observe, exploit, search for topics and have the opportunity to convey the most authentic information to the audience.

I don’t think of myself as a hero, but as a messenger. In a life-or-death situation, I would choose to keep the team safe and put my own life first. However, as a journalist, there are times when you have to take risks to capture precious moments and documents. At these times, skills and the ability to assess the actual situation are extremely important to help reporters capture that moment in a safe manner. If life is at stake, safety is still the top priority.

How has your experience in Myanmar impacted you as a person?

I am a very individualistic person. But after this assignment, my perception of life has changed. I find myself more calm, more caring towards people. I cherish every meal with my parents. I cherish every hug with friends, with everyone. The most valuable lesson I have learned is to appreciate this life. Appreciate all the feelings I have. Appreciate the job I am doing. I also live more slowly and more deeply.

Perhaps, when faced with the moment of life and death, I understand that life is impermanent so I cherish every moment.

If you weren't a journalist, what kind of person would you be? Would you still be as individual and daring as you are now?

Since childhood, I have always thought that I have to be bold and responsible. Journalism has fostered those qualities in me, but also made me more courageous. After each job, I draw a certain lesson about life and philosophy. Before that, I was an actor. Besides journalism, I love both jobs. Because I feel like I have lived many lives, in many contexts. In each life, each context, I have learned lessons. And my life, because of that, is more colorful.

I often joke that, once you come to earth, live a brilliant life. Up to this moment, I feel like I have lived a brilliant life.

Thank you for sharing today!

Publication date: June 19, 2025

Production organization: Hong Minh

Content: Ngoc Khanh, Son Bach, Uyen Huong

Photo: Son Tung

Concept: Ta Lu

Presented by: Thi Uyen

Source: https://nhandan.vn/special/nha-bao-thanh-van/index.html#source=home/zone-box-460585

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs the Government's online conference with localities](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/5/264793cfb4404c63a701d235ff43e1bd)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh launched a peak emulation campaign to achieve achievements in celebration of the 14th National Party Congress](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/5/8869ec5cdbc740f58fbf2ae73f065076)

![[Video] Jelly Mooncakes: New Colors for the Mid-Autumn Festival](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/5/abb1d390ee7f452b9110fca494ba0d77)

![[Video] Traditional moon cakes attract customers](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/5/0a98992e8c92419fa9ea507de23e365d)

![[VIDEO] Summary of Petrovietnam's 50th Anniversary Ceremony](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/4/abe133bdb8114793a16d4fe3e5bd0f12)

![[VIDEO] GENERAL SECRETARY TO LAM AWARDS PETROVIETNAM 8 GOLDEN WORDS: "PIONEER - EXCELLENT - SUSTAINABLE - GLOBAL"](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/23/c2fdb48863e846cfa9fb8e6ea9cf44e7)

Comment (0)