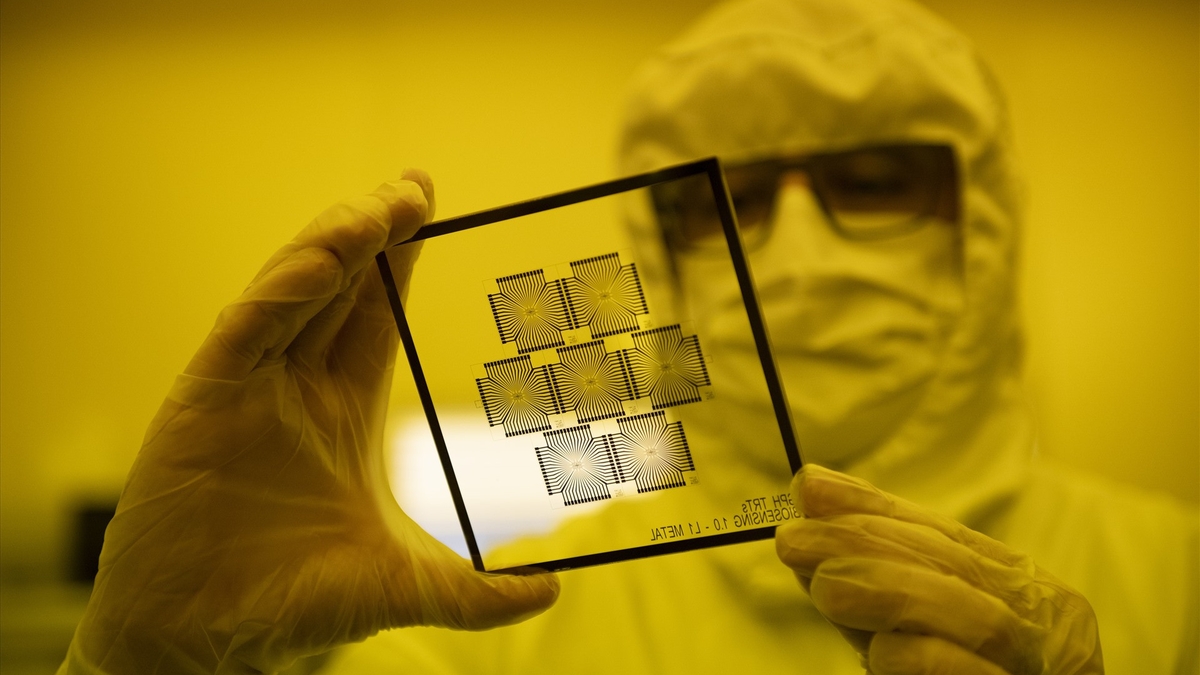

Widespread aspen trees were a common sight in Yellowstone National Park before wolves were removed. (Photo: Science Alert).

A new study has revealed a remarkable story of ecological restoration in Yellowstone National Park, where the return of gray wolves has helped revive disappearing aspen forests.

In the early 20th century, the decision to completely remove gray wolves from Yellowstone inadvertently set off a negative ecological chain reaction. Without a natural predator, elk populations exploded, becoming a serious threat to vegetation, especially young aspen trees.

They eat the tops, strip the bark and trample the forest floor, leaving many forests barren and bare. As a result, species that depend on canopy cover, such as birds, beavers and insects, gradually disappear.

Ecologists have been documenting this severe decline since 1934, but all attempts to intervene have had little apparent effect. The root cause lies not in the vegetation, but in the crucial ecological link that has been severed: the absence of apex predators.

The wolf returns, the poplar forest revives

The turning point came in 1995, when gray wolves were reintroduced into Yellowstone from Jasper National Park, Canada. This was considered one of the most audacious ecological restoration efforts in the United States. The wolves quickly adapted, established territories, and began performing their natural role: controlling the elk population.

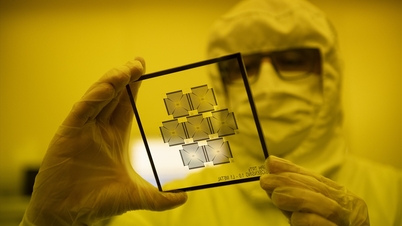

Two gray wolves stand on a moose carcass in Yellowstone National Park (Photo: Science Alert).

The presence of wolves forced elk to move more frequently, avoiding areas prone to predation. This gave young plants, which were previously frequently eaten and trampled, a chance to survive and thrive. This is a classic example of a “top-down chain effect”, where a predator at the top of the food chain impacts the entire ecosystem below.

Nearly three decades after the reintroduction of wolves, scientists have observed a remarkable recovery. New research by a team led by Professor Luke Painter of Oregon State University shows that about a third of the 87 aspen forests surveyed in Yellowstone now have a thriving sapling layer. This is the first generation of trees to form a canopy layer, something that hasn’t happened since the 1940s.

Specifically, 43% of the areas examined recorded saplings exceeding the 5cm stem diameter threshold, indicating long-term survival. The density of trees over 2m tall has increased 152-fold since the late 1990s. The landscape also varied significantly, with 30% of the forest area having dense trees and 32% having scattered trees.

To confirm the role of wolves, the team measured the rate of tree destruction by moose in each area. The results showed that forests with a regular wolf presence recorded much lower rates of tree destruction, while areas without wolves continued to destroy saplings and failed to develop into a forest floor.

Professor Painter said this was a remarkable case of ecological restoration, where humans did not need to plant more trees or build more dams, but simply gave nature back the missing link. The return of wolves opened the door for the aspen forest, and with it countless other species, to recover after decades of decline.

Source: https://dantri.com.vn/khoa-hoc/su-tro-lai-cua-loai-soi-giup-rung-yellowstone-hoi-sinh-the-nao-20250730084800356.htm

![[Photo] Da Nang: Hundreds of people join hands to clean up a vital tourist route after storm No. 13](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/07/1762491638903_image-3-1353-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)