The fact that Man City sold Cole Palmer or Chelsea sold Mason Mount this summer shows that youth team talent has now become a source of income, not a foundation to build a club in the Premier League.

How to build a football dynasty? For decades, the traditional and sustainable formula has been to build a talented youth team, recruit new stars and have pillars – players with leadership qualities and long-term commitment to the club – set the standards, helping to control the dressing room with the manager.

The great clubs of European football, almost all of which have their foundations in youth development - such as Pep Guardiola's Barca, Arrigo Sacchi's Milan with its foundation of experienced midfielders and defenders, Johan Cruyff and his teammates who came through the Ajax youth team, or Bayern Munich led by Franz Beckenbauer - all follow the above template.

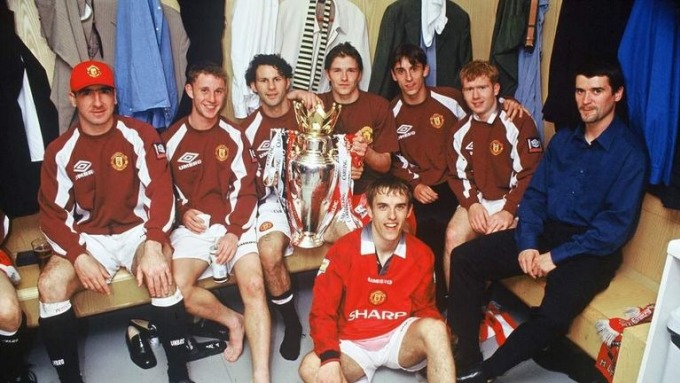

The same thing happened in English football, with Man Utd's "Class of 92" or Don Revie's Leeds - including players who grew up together in the academy, stuck together, developed together, matured and then achieved success.

Man Utd, with the Class of 1992 and the stars they bought such as Eric Cantona (in hat) and Roy Keane (right), were once seen as a model for success by building a strong team from academy talent. Photo: Sky Sports

Liverpool of the 1970s and 1980s bucked that trend by recruiting talent from the lower leagues, but also local players such as Tommy Smith, Phil Thompson and Jimmy Case. Nottingham Forest under Brian Clough were strong in Peter Taylor’s recruitment skills, but the key player was John Robertson, who joined the team at the age of 17. Similarly, Chelsea in the Abramovich era had success with John Terry, a centre-back who joined at 15.

But that formula doesn’t seem to work in today’s football . In today’s world, it’s likely that the likes of David Beckham, Paul Scholes and John Terry would be sold long before they’ve reached their peak. Youth teams are now a source of income rather than a building block for a club, a sign that football is becoming a big business rather than a sporting , community endeavor.

In the fourth round of the Premier League, Cameron Archer scored his first goal for Sheffield United against Everton, Billy Gilmour played as a link-up player in Brighton's midfield, Lewis Hall was on the bench for Newcastle, and Cole Palmer played the final 38 minutes of Chelsea's 0-1 home loss to Nottingham Forest.

What all these names have in common is that they are all young talents who are sold as soon as they get a good price. Just last season, Archer was a gem for Aston Villa's youth team. Gilmour was once expected to become Chelsea's Andres Iniesta. Hall - who joined Chelsea at the age of 8 - was the academy's best player last season. Palmer made the Manchester City first team last season and has recently been considered a quality addition to the defending champions' midfield, scoring in both the Community Shield and the UEFA Super Cup.

Palmer (blue shirt) made his Chelsea debut in the loss to Nottingham Forest on September 2, after being bought from Man City. Photo: PA

Money is the core reason why fewer and fewer young players come through the academy and then flourish in the first team of the same club. Under the Financial Fair Play (FFP) regulations, players who come through the academy are counted as free of transfer fees, so the money earned from selling them is net profit. And with FFP tightening up many regulations after a period of relaxation due to Covid-19, the lure of net profit means that clubs no longer hesitate much when it comes to making money from academy talent.

Gilmour - who Chelsea paid a $625,000 development fee to sign from Rangers when he was just 16 - was counted as a pure profit when Chelsea sold him to Brighton for $10 million last summer. Palmer joined Man City's academy when he was just eight, so was not counted as a signing-on fee, and made a net profit of $50 million from his transfer to Chelsea this summer.

In fact, some clubs have long used youth teams as a way to make money. Man Utd in the 1990s and 2000s sold talent that was not part of Sir Alex Ferguson’s plans. But in the latest trend, even academy players who have grown up, become mainstays of the first team and are expected to become legends can be sold. Once expected to stick with Chelsea for their entire top-flight careers like seniors John Terry and Frank Lampard, Mason Mount was sold to Man Utd this summer for £50 million.

"Players like Mount once helped maintain Chelsea's identity. But in an era of foreign ownership and global appeal, such local players have become redundant," commented the British newspaper Guardian .

Perhaps only Arsenal, with Bukayo Saka beloved by fans and Eddie Nketiah trusted by Mikel Arteta as a reserve striker, adhere to a traditional style of football.

Chelsea made $76 million from Mount's sale, reinvesting a $1 billion-plus spend under new owner Todd Boehly in just one year on cheaper, longer-term players. Before Mount, Chelsea sold academy products Ruben Loftus-Cheek, Ethan Ampadu and Callum Hudson-Odoi for a combined $125 million, all players with great potential, part of a team that reached nine finals and won the FA Youth Cup seven times in 11 years.

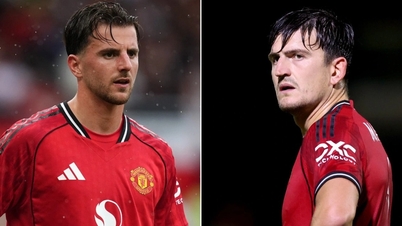

Mount (left) is the latest name in the group of young stars who grew up from the academy to be sold by Chelsea, after Callum Hudson-Odoi, Tomori and Tammy Abraham. Photo: Chelsea FC

And Chelsea is no exception. This summer, despite parting ways with Fred, Man Utd spent most of the transfer window trying to sell Scott McTominay - a defensive midfielder who came through the academy - for $50 million, but failed. Cameron Archer went to Sheffield United for $22 million, becoming the next Aston Villa Youth Cup winner in 2021 to leave the team, following Aaron James Ramsey (to Burnley) and Carney Chukwuemeka (to Chelsea).

In addition to Palmer's $45 million, Man City has made a lot of money selling players who have no chance of competing for a first-team place. Last year, Southampton spent a total of $48 million to bring in Gavin Bazunu, Juan Larios, Samuel Edozie and Romeo Lavia from Man City. Of that, Lavia joined Chelsea for $63 million this summer, and 20% of this money will go to Man City.

The Etihad Stadium owner also earned 24 million USD from selling James Trafford - a player who has never played for the first team - to Burnley and parting ways with Tommy Doyle and James McAtee on loan. Currently, defender Rico Lewis is the only academy product who can follow Phil Foden to become a mainstay of the first team.

"When everything in football has a price, players of the future will immediately become assets that can be sold for profit. Anyone who wants to build a modern football dynasty will have to pay for players from other teams, instead of using homegrown talents," commented the Guardian .

Hong Duy (according to Guardian )

Source link

![[Photo] Da Nang: Hundreds of people join hands to clean up a vital tourist route after storm No. 13](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/07/1762491638903_image-3-1353-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)