Around December 25 and 26, my parents brought home heavy skewers of meat that were divided at the office. My father worked hard to wash, slice, and divide them into portions: one for making jelly, one for marinating char siu, one for making banh chung filling, etc.

Around December 25 and 26, my parents brought home heavy skewers of meat that were divided at the office. My father worked hard to wash, slice, and divide them into portions: one for making jelly, one for marinating char siu, one for making banh chung filling, etc.  Mom went in and out to help Dad, always saying, “Being full for three days of Tet, hungry for three months of summer, how nice it would be to have enough for the whole year like this.” Dad carefully put the best, freshest strips of pork belly into the big pot with the instruction, “Use this to wrap banh chung!”

Mom went in and out to help Dad, always saying, “Being full for three days of Tet, hungry for three months of summer, how nice it would be to have enough for the whole year like this.” Dad carefully put the best, freshest strips of pork belly into the big pot with the instruction, “Use this to wrap banh chung!”  While watching Dad divide the meat attentively, my sister and I said “yes” loudly. In our minds at that time, the meat used for the filling was very important, much more important than the other char siu and jellied meat, and we couldn’t explain why.

While watching Dad divide the meat attentively, my sister and I said “yes” loudly. In our minds at that time, the meat used for the filling was very important, much more important than the other char siu and jellied meat, and we couldn’t explain why.  The stage that the children look forward to the most is wrapping banh chung. This important task is done by our grandparents. We busily sweep the yard, spread out mats, carry dong leaves… then sit neatly around waiting for our grandparents. The green dong leaves are washed clean by our mother, dried, carefully stripped of the midrib, and neatly arranged on the time-glossy brown bamboo trays.

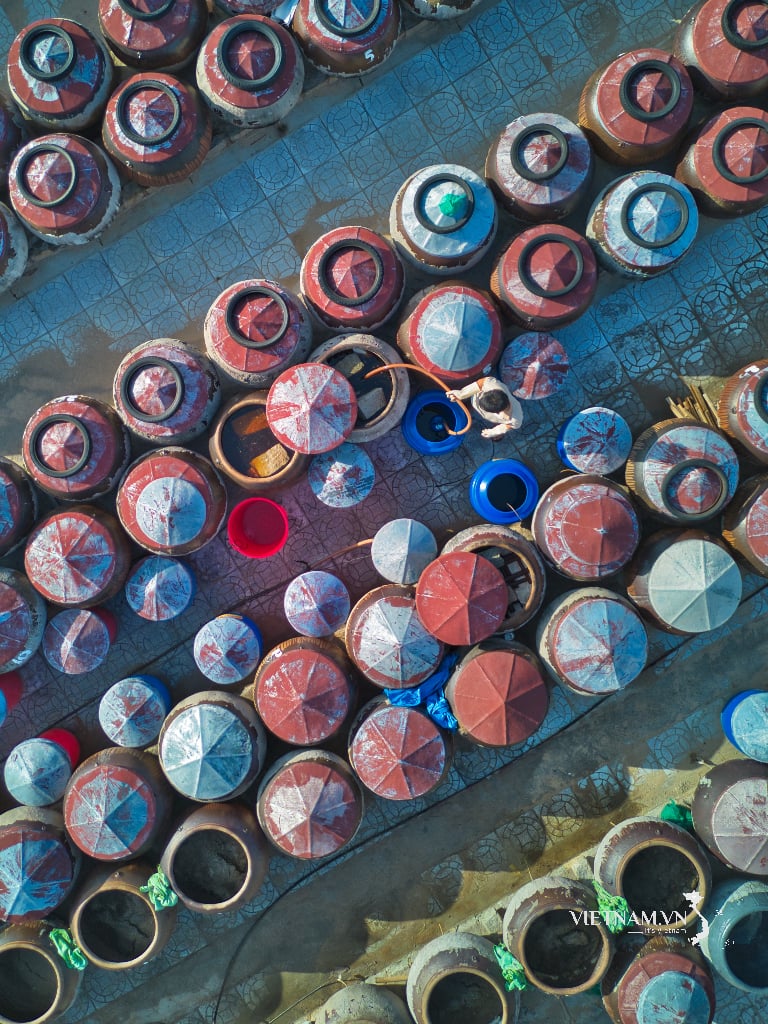

The stage that the children look forward to the most is wrapping banh chung. This important task is done by our grandparents. We busily sweep the yard, spread out mats, carry dong leaves… then sit neatly around waiting for our grandparents. The green dong leaves are washed clean by our mother, dried, carefully stripped of the midrib, and neatly arranged on the time-glossy brown bamboo trays.  The round, golden mung bean balls were already sitting in the earthenware pot next to the basket of pure white sticky rice, full to the brim. The pork belly was sliced into pieces, seasoned with a little salt, mixed with pepper, chopped shallots… Everything was in place, just waiting for the grandparents to sit down on the mat for the wrapping to begin.

The round, golden mung bean balls were already sitting in the earthenware pot next to the basket of pure white sticky rice, full to the brim. The pork belly was sliced into pieces, seasoned with a little salt, mixed with pepper, chopped shallots… Everything was in place, just waiting for the grandparents to sit down on the mat for the wrapping to begin.  But, every year, even though my parents had prepared all the ingredients; even though my three sisters and I had each taken a position, one next to the tray of dong leaves, one next to the pot of mung beans… my grandfather still looked around and asked, “Are you all here?” before slowly going to the well to wash his hands and feet. Before that, he had also changed into a new shirt and put on his head a turban that was only used on important holidays and New Year’s.

But, every year, even though my parents had prepared all the ingredients; even though my three sisters and I had each taken a position, one next to the tray of dong leaves, one next to the pot of mung beans… my grandfather still looked around and asked, “Are you all here?” before slowly going to the well to wash his hands and feet. Before that, he had also changed into a new shirt and put on his head a turban that was only used on important holidays and New Year’s.  Grandma was already wearing a purple shirt, chewing betel while waiting for him. I, a 12-13 year old girl, kept wondering why every time he wrapped banh chung, my grandfather required the three of us to be present. Our participation only made my grandparents busier, because sometimes the youngest son dropped sticky rice all over the mat, sometimes the second son was caught red-handed eating mung beans…

Grandma was already wearing a purple shirt, chewing betel while waiting for him. I, a 12-13 year old girl, kept wondering why every time he wrapped banh chung, my grandfather required the three of us to be present. Our participation only made my grandparents busier, because sometimes the youngest son dropped sticky rice all over the mat, sometimes the second son was caught red-handed eating mung beans…  However, he still asked my mother to arrange a banh chung wrapping session on the weekend so that we could all participate. The time waiting for him to complete the procedures before wrapping the banh chung was very long, but in return, the wrapping was fun, because each of us was guided by our grandparents. Three small, crooked, loose cakes “just like a bundle of shrimp paste” (according to my mother) lay next to the square, even cakes, the white color standing out against the green dong leaves, looking like little piglets cuddling next to their parents and grandparents.

However, he still asked my mother to arrange a banh chung wrapping session on the weekend so that we could all participate. The time waiting for him to complete the procedures before wrapping the banh chung was very long, but in return, the wrapping was fun, because each of us was guided by our grandparents. Three small, crooked, loose cakes “just like a bundle of shrimp paste” (according to my mother) lay next to the square, even cakes, the white color standing out against the green dong leaves, looking like little piglets cuddling next to their parents and grandparents.  Then the pot was put on, each cake was carefully placed in the pot, one on top and one on the bottom, neatly and in a straight line; then the big logs were slowly filled with fire, the fire gradually became red, from pink to bright red, occasionally crackling. All of this created an unforgettable memory of our poor but happy childhood years. Thanks to the late afternoons with our grandparents, now we all know how to wrap cakes, each square and sturdy as if using a mold.

Then the pot was put on, each cake was carefully placed in the pot, one on top and one on the bottom, neatly and in a straight line; then the big logs were slowly filled with fire, the fire gradually became red, from pink to bright red, occasionally crackling. All of this created an unforgettable memory of our poor but happy childhood years. Thanks to the late afternoons with our grandparents, now we all know how to wrap cakes, each square and sturdy as if using a mold.Heritage Magazine

![[Photo] Opening of the 14th Conference of the 13th Party Central Committee](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/05/1762310995216_a5-bnd-5742-5255-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Opening of the 14th Conference of the 13th Party Central Committee](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/05/1762310995216_a5-bnd-5742-5255-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Government holds a special meeting on 8 decrees related to the International Financial Center in Vietnam](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/04/1762229370189_dsc-9764-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Panorama of the Patriotic Emulation Congress of Nhan Dan Newspaper for the period 2025-2030](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/04/1762252775462_ndo_br_dhthiduayeuncbaond-6125-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)