Hairdresser Pyo had pins hidden in his shoes, his head forced down the toilet, and his stomach kicked, but it took many years for him to speak out.

The 26-year-old is part of a wave of “Hakpok” victims coming forward to report bullying they suffered in school years ago. The movement is spreading from the entertainment world to the sports world. The accusations, often anonymous, can end the careers of major stars.

Pyo Ye-rim endured everything alone in school. She said her teachers did not address the bullying, but instead told her to “be nicer” to her classmates. She eventually gave up her dream of going to college and went to vocational school.

"At that time, I only wished for one thing, that someone could help me," Pyo said. "But no one came and I escaped, fighting to survive on my own."

South Korea is a country that places a high valueon education , where children can spend up to 16 hours a day in school and after-school tutoring. But experts say bullying is widespread, despite efforts to intervene.

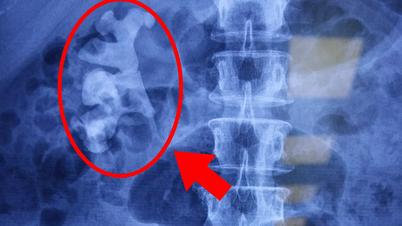

Hairdresser Pyo Ye-rim speaks to the media at her salon in Busan, South Korea, March 29. Photo: AFP

The Hakpok wave exploded after the buzz of the movie The Glory , about a woman's elaborate revenge plan after years of brutal abuse in high school. The movie heated up the discussion about school bullying nationwide.

Ironically, after the film became popular, the film's director, Ahn Gil-ho, was accused of bullying his classmates and later had to apologize.

The "Hakpok" movement is so widespread that the South Korean presidential office had to reverse the appointment of a police chief, after information that his son bullied his classmates.

"School violence is a common disease in Korean schools, leading to 'collective trauma' that the country needs to deal with," said Noh Yoon-ho, a lawyer who specializes in bullying cases in the capital Seoul.

“Every Korean has been a victim or witnessed bullying without help. We all have memories of it,” said Noh, adding that the Hakpok movement has helped many people shed the shame of their experiences.

Before deciding to speak out, Pyo struggled with insomnia and depression. Her hairdresser’s late complaint led to one of Pyo’s bullies being fired, but she is campaigning for changes in the law to better protect victims.

A scene from the movie "The Glory". Photo: Korea Herald

In the Hakpok movement, victims speak out years after the bullying has occurred. Anti-school violence activists say bullies are not held accountable while they are still in school.

Pyo and other victims say South Korea should eliminate the statute of limitations for school violence, so that bullies can be held accountable, even decades later. But Noh, the lawyer, says prosecuting adults for crimes committed as minors is a difficult task.

Despite widespread public support for the victims, some have questioned the fairness of the anonymous accusations that have led to the downfall of many high-profile figures. An Woo-jin, one of South Korea’s most successful baseball players, was kicked out of the national team after it was revealed he had bullied his high school teammates.

Meanwhile, Pyo points out that victims have to report anonymously because they fear that the bully will use defamation laws to sue the victim. In many cases, the bully wins the lawsuit, even when the victim tells the truth. Pyo is calling for changes to defamation laws.

“This is why most of the complaints are anonymous. Without defamation laws, countless victims would start speaking out,” she said.

Experts say the best approach is to deal with school bullying as soon as it occurs, as this will provide clear evidence and ensure fairness for both parties. "The problem is that Korea does not have a school-level mechanism that victims can approach without hesitation, so that bullying cases can be dealt with quickly and appropriately as soon as they occur," said Jihoon Kim, a criminology professor.

Duc Trung (According to AFP )

Source link

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam works with the Central Policy and Strategy Committee](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/28/7b31a656d8a148d4b7e7ca66463a6894)

![[Photo] Vietnamese and Hungarian leaders attend the opening of the exhibition by photographer Bozoky Dezso](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/28/b478be84f13042aebc74e077c4756e4b)

![[Photo] 12th grade students say goodbye at the closing ceremony, preparing to embark on a new journey](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/28/42ac3d300d214e7b8db4a03feeed3f6a)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh receives a bipartisan delegation of US House of Representatives](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/5/28/468e61546b664d3f98dc75f6a3c2c880)

Comment (0)