The story of university scores in Vietnam reflects a long journey of transformation - Illustration photo AI

Memories of a time "suffocating"

Let's go back in time to the early 2000s, in prestigious universities with strict grading cultures such as Architecture, Polytechnic, Medicine and Pharmacy. There, "stingy grading" had almost become an unspoken norm maintained for many generations.

No matter how elaborately and carefully invested an architectural project is, it is difficult to surpass the threshold of a 7. A score of 8 is already a proud achievement, while a score of 9 is so rare that it has become a legend, often "saved" by teachers as a testament to the standard of excellence for future generations to refer to.

Behind that strictness lies a clear educational philosophy: real life is much harsher. A “real” score will help students soberly recognize their true abilities, overcome complacency to constantly improve themselves. It is essentially a lesson in humility and the will to learn.

However, the consequences of this philosophy are not without their downsides. It creates a paradox worth pondering: it is the "modest" transcripts with a series of 5s and "save" 5s that become a burden for students when entering the labor market or hunting for scholarships to study abroad.

In the eyes of many employers or international universities - especially in European universities, where there is often a minimum GPA threshold - those scores are easily misunderstood as limited ability, unintentionally closing many valuable opportunities regrettably for capable students.

The turning point of the credit system and the paradox of instability

The big turning point came with the widespread application of the credit-based training system and the 4-point scale. Our class of 2009 at the School of Architecture was one of the first to experience this transformation. A paradox arose: while the school still maintained the "suffocating" grading standard on a 10-point scale, to get an A (4.0) on a 4-point scale, students had to achieve a minimum of 8.5/10.

The result was predictable. Our transcripts were pitifully “modest” when converted to a letter grade. The best students stopped at B (3.0) - which is just enough to graduate, according to the requirements of some American universities (students must maintain a minimum GPA of 3.0/4.0 to graduate).

We, the insiders, were in a confusing situation: we tried our best but the results on the transcript could not compare with other schools, even being disadvantaged when studying abroad or applying for jobs at multinational companies. Teachers were equally confused, between old grading habits and the pressure of a new system.

The era of "point inflation" and its unpredictable consequences

While memories of the "suffocating" scores of the previous generation have not faded, the reality of university education today reveals a paradox.

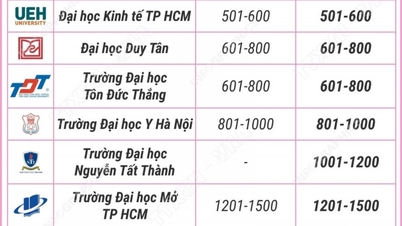

In the media, we easily come across astonishing numbers: the rate of excellent and good graduates at many major universities is constantly increasing, even in some places by 2025, this number is recorded to far exceed the 80% threshold.

A careful analysis of recent years' graduate ranking data reveals a striking trend: a steady, sometimes dramatic, increase in the proportion of students achieving high honors.

In particular, at key training institutions in the economic sector, the rate of excellent and good graduates is not only high but also overwhelming, accounting for the majority of the total number of bachelors awarded degrees.

This disparity inevitably raises questions about the uniformity of assessment standards between training fields, and more importantly, about the true meaning of good degrees in today's labor market.

The reason is not mysterious. It lies in the grading system. With the regulation that a student only needs to score 8.5/10 to receive an A - the highest grade - a tendency to "loosen" the grading criteria has been unintentionally encouraged. As a result, classes with 50%, even 70-80% of students getting A are no longer rare.

The consequences of “grade inflation” do not stop at beautiful transcripts. It also destroys the core function of grades: the differentiation of real ability. When everyone is good, no one is really good in the eyes of employers.

They are forced to dig deeper, using complex screening tools such as aptitude tests, behavioral interviews, or assessment centers to conduct additional tests (assessment centers ), leading to a significant increase in recruitment costs and time. The real value of a university degree is therefore challenged.

"Bell Curve" - Miracle or Necessary Bitter Medicine?

In this context, the "bell curve" is mentioned as a possible technical solution to control inflation. The core of the bell curve does not lie in changing the way of teaching or grading . We also do not need to reform or change the way of grading or assessment as before, but the change lies in the final conversion and grading.

Instead of a fixed A grade threshold that is directly converted to A, B, C, or D grades, this method ranks students based on the relative distribution of ability across the class. Only a certain percentage (e.g., 10-15%) will get an A grade, the majority will be B or C, and a small fraction will be D.

This method, which is applied at many international universities such as Stanford, Harvard or right at RMIT Vietnam, helps ensure that scores reflect a student's position in the group relatively accurately, thereby controlling the situation of "all A's", or the whole class only having 5's, "salvage" 5's... just enough to pass the subject.

Its benefits are clear: restoring differentiation, enhancing the value of qualifications, and giving employers a more reliable measure.

However, the story is not all rosy. The Bell curve also has undeniable downsides. It can create unnecessary and sometimes unfair competition.

In a class full of excellent students (such as a high-quality class or a gifted class), a truly capable student, even if he or she scores well on the test, may still only receive a B or C if they are not in the top of the class, or if there are many people who score higher than them. This method also has the limitation that it can "make it difficult" for good students who are in an environment full of good students; or when a class has too few students.

So what is the solution?

The Bell curve is not a magic bullet, and applying it rigidly will only replace one problem with another. The solution may lie in a more balanced and flexible evaluation philosophy.

First , there needs to be flexibility in application. The grade distribution ratio in the bell curve should not be a rigid number (for example, if there is an exam, only 10% of students can get an A, 30% can get a B) for all subjects and all classes; but should be adjusted and balanced based on the characteristics of each field (engineering, art, business...), or class size and even input quality.

Second , and perhaps more importantly, we need to change our thinking about the purpose of grades. Grades should not be the end goal, but only a means of feedback for the learning process. The core value of a university education lies in the knowledge, skills, and thinking that students acquire, not a pretty number on a diploma.

Ultimately, finding an assessment method that properly recognizes individual efforts while ensuring objectivity, transparency, and classification is the key to enhancing the real value of Vietnamese university degrees in the new era. It is a journey that requires the cooperation of not only educational administrators, but also lecturers, students, and the business community.

Source: https://tuoitre.vn/chuyen-diem-so-o-dai-hoc-viet-nam-tu-thoi-ky-kho-tho-den-cau-chuyen-lam-phat-diem-20251010231207251.htm

![[Photo] Dan Mountain Ginseng, a precious gift from nature to Kinh Bac land](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F11%2F30%2F1764493588163_ndo_br_anh-longform-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)