In Daechi-dong, not only university students, but also pre-school students have to go to class and study day and night to compete for admission to elementary schools.

In a brightly lit classroom in Daechi-dong, Seoul, South Korea, 4-year-old Tommy is busy writing a test with a pencil in hand. His little hands are shaking slightly, and his feet are dangling, barely touching the ground.

Outside the classroom, Tommy’s mother and other parents waited anxiously. Even at the age of four, their child had to read an English text, answer comprehension questions, make inferences, or write a perfect essay within 15 minutes.

This is not an exam for ordinary kindergarteners, but preparation for the “four-year-old exam” – a term coined by ambitious parents in this wealthy neighborhood, where children who have not yet entered kindergarten are required to attend school and have their own study program.

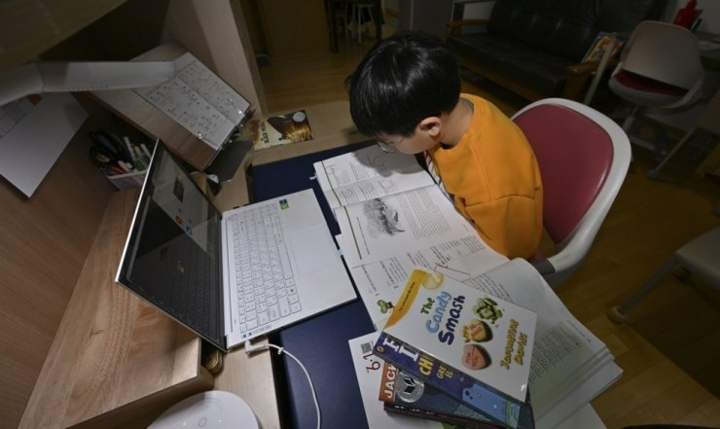

The dark side inside the most notorious tutoring 'capital' in Korea. (Illustration photo)

Race to kindergarten

In Korea, Daechi-dong has also gradually become the notorious "capital" of learning. This place is famous for its culture of non-stop studying, dominated by cram schools and centers.

Now, the place has expanded its reach to children barely old enough to hold a pencil, so parents like Tommy’s are not only preparing their children for primary school, but also pushing them to study for entrance exams at English-medium kindergartens.

Parents in Daechi-dong told the Korea Herald that an English-only kindergarten is the first step to ensuring their children's successful future in South Korea, where Korean is the official language and English is not widely spoken.

A mother whose child is studying at an English-only kindergarten said that such "exclusive" institutions help children immerse themselves in an English-only environment, with all teachers being foreigners, no Koreans. "Studying at such a school is considered a golden ticket for my child to speak English fluently, and then will have a head start in the race to enter elite schools," the mother shared.

To ensure their children achieve good results in these entrance exams, Korean parents register their children in centers that specialize in exam preparation for 4-year-olds.

These centers not only teach children English, but also train them in test-taking skills, such as learning to recognize English letters, conversing with teachers in English... These children even have to learn how to behave in class, hold a pencil properly and know how to go to the toilet by themselves.

"The children are still very young, so we start with 30-minute classes. Once they get used to being away from their parents, we will hold one-hour classes," an information center employee told The Korea Herald.

South Korean children take extra classes from a young age because their parents believe that academic performance is a condition for success. (Photo: Yonhap)

English is more important than mother tongue

To help their children pass the exams, many parents spend hundreds of dollars hiring tutors and buying exam preparation books for their children to review old exam questions. Not stopping there, some people also spend money to ensure their children have a place in school because the demand for enrollment in exam preparation centers is very high.

Parents pay nearly $1,400 a month in tuition at these centers, but many families are willing to pay double that for private tutoring to ensure their children keep up with the rigorous curriculum. These centers also assign homework, in the form of English-language kindergartens, to ensure children do not fall behind their peers.

Sharing about letting her child learn English from a young age, Ms. Kim (39 years old) said that she enrolled her child in one of the most famous English kindergartens in Daechi-dong. Since going to school, she has had to call her child by his English name, even at home.

"I tend to call my child by his English name so he gets used to hearing English. He also refuses to speak Korean at home. Therefore, my husband and I always try to communicate with him in a foreign language," Ms. Kim shared.

Although her daughter speaks fluent English, Kim admits that her daughter struggles with basic Korean words like “butterfly” and “doll” – the first words Korean children learn. However, the mother believes that learning English is more important.

For many parents in Daechi-dong, letting their children learn English early is not simply about learning a language, but also about removing obstacles in their children's future. When they enter elementary school, when other children are just starting to learn English, they can focus on advanced subjects, especially math.

Parents in Daechi-dong believe that an early start is the best way for their children to succeed in South Korea's fiercely competitive education system. As such, the race is not limited to English, but involves other subjects as well.

A tutoring center counselor who once sent her child to Daechi-dong said English is only one part of the competition. As for math, the tutoring capital has an unwritten rule that third-graders must complete the sixth-grader curriculum. Some children are already learning calculus as early as fifth grade.

The “studying years ahead” mentality has been ingrained in Daechi-dong for decades. English, math and other subjects are all believed to help Daechi-dong children get into a top university.

The downside

Although Daechi-dong is considered the tutoring capital of the country, not all parents support the competition. One mother, who recently moved to Gangnam, said she opposes the extreme trend and just wants her son to be happy. “I don’t want him to be part of this crazy competition,” she insisted.

The mother, it is worth mentioning, paid the price for her thinking. As her son fell further and further behind his peers, she felt pressured to help him learn even the most basic things. Now, the woman must ask herself whether opposing the learning trend was the right choice.

However, what worries the mother more is the increasing number of children with mental health problems, especially tic disorders. "Before, these things were often hidden. But now, because so many children are going through this, mothers openly share recommendations from doctors, just like how they share information about extra classes," the mother said.

According to the Korean government , in the past five years, the number of children aged 7-12 diagnosed with depression or anxiety disorders has doubled, from 2,500 in 2018 to 5,589 in 2023. Gangnam, Songpa, Seocho-gu - the educational "holy lands" of Seoul - are the places with the highest number of children with mental health problems.

The intense academic pressure in Daechi-dong is an "open secret." Parents talk about their children's mental health problems as freely as they discuss test scores.

Childhood stress – once considered a minor concern – is now a well-documented crisis in the region, but many parents say they have no choice.

"I have lived in Daechi-dong for more than 20 years. As a mother who works in this industry, I know that parents cannot do anything else. Parents believe that the race will continue as academic success is still what determines a child's future," the mother said.

Source: https://vtcnews.vn/mat-toi-ben-trong-thu-phu-day-them-khet-tieng-bac-nhat-han-quoc-ar929528.html

![[Photo] "Ship graveyard" on Xuan Dai Bay](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/08/1762577162805_ndo_br_tb5-jpg.webp)

![[Video] Hue Monuments reopen to welcome visitors](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/05/1762301089171_dung01-05-43-09still013-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)