The "bell curve" (or "grading curve") grading method is attracting a lot of attention, especially in education today. In Vietnam, in my opinion, this assessment method can more accurately reflect students' abilities. However, it needs to be applied flexibly and appropriately to the actual context.

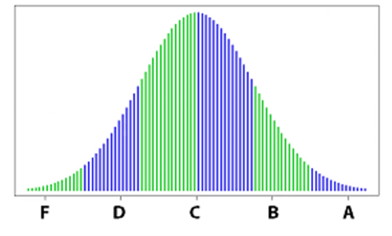

The bell curve, also known as the "bell curve," is a graph that represents a normal distribution. It shows that most values are concentrated in the middle, with a few values falling on the outer edges (i.e., too high or too low). For example, in a classroom, the majority of students will have average or above-average grades, while only a few will have very high or very low grades.

A bell-shaped histogram represents a normal distribution.

One of the key benefits of this assessment method is its ability to control "grade inflation," a growing concern in Vietnam. Currently, many graduating classes have more than half of their students achieving good or excellent grades, diminishing the value of the degree and discouraging students from striving for high scores. When grades are consistently high, it becomes difficult to distinguish between truly capable individuals and those who have benefited from a lenient grading system.

Currently, universities in Vietnam use a 10-point scale for exams and average grades, which are then directly converted into ABCD classifications based on fixed scores. For example, if a student scores between 8.5 and 10, they will be classified as A; between 7 and 8.4 as B; between 5.5 and 6.9 as C; and a score of 4 or higher will be considered D.

This method is simple and easy to understand, helping students grasp the grading criteria. However, it can easily lead to grade inflation, with too many students achieving high scores that don't accurately reflect their abilities. Conversely, in arts, painting, literature, architecture, and other fields, students typically receive average grades, rarely high or perfect scores. This inadvertently creates a disadvantage in the comparative evaluation between different art schools.

The "bell curve" grading system doesn't rely on fixed scores but rather on a normal distribution of grades within the class. After students receive grades on a 10-point or 100-point scale, instructors adjust grades based on the relative distribution of the entire class. Only a small fraction, about 10-20%, are graded A, followed by Bs, and the majority of students fall into Cs and Ds. This method helps prevent grade inflation by limiting the number of students receiving high grades, ensuring an accurate reflection of the differences in ability among students.

For example, in a class of 100 students, if grading on a 10-point scale, an exam that's too easy might result in the entire class receiving an A, or if it's too difficult, the whole class might only get C or D. With the bell curve method, even if the exam is difficult and the average score is 5/10, the class will still have approximately 10 students receiving an A, 40 students receiving a B, 40 students receiving a C, and 10 students receiving a D. This helps distribute scores more fairly and accurately reflects students' abilities.

Another benefit of the "bell curve" is its flexibility and objectivity. In traditional assessment methods, instructors grade based on fixed standards, sometimes failing to accurately reflect the differences between classes, subjects, or universities. With the "bell curve," students' scores are compared to their classmates, providing a more comprehensive and fair assessment of each individual's true abilities, rather than relying solely on a rigid 10-point scale converted to letter grades.

The "Bell curve" allows recruiters to more accurately assess a candidate's abilities during the hiring process (Illustrative image: CV).

As I mentioned above, the "bell curve" only applies during the transition from numerical scores to letter grades, and has absolutely no difference or influence on teaching, grading, and student evaluation as it has always been, nor does it require universities to scramble to find ways to "tighten" graduation standards.

Some university programs, such as RMIT University Vietnam, have also adopted the "bell curve" assessment system to ensure that student scores are evaluated fairly and in line with global standards.

During my time at Stanford (USA), after each exam, the instructors clearly and transparently announced the graded score on a 100-point scale and the class average score, along with a graph showing the distribution of the scores, to the entire class.

The "Bell curve" also allows employers to more accurately assess candidates' abilities during the recruitment process. When scores are no longer inflated, qualifications become more valuable and accurately reflect the learner's capabilities. This helps businesses select truly competent candidates, thereby improving the quality of their workforce.

However, this isn't a perfect method either. The "bell curve" itself creates competitive pressures and unspoken injustices. A student might score quite high on an exam, for example, an 8 out of 10, but if other students in the class also score high, they might still only get a C.

This can create unfairness in classes that already have many high-achieving students, such as gifted programs. Furthermore, in classes with few students or where there isn't significant variation in ability, the "bell curve" may not be fully effective and could lead to biased assessments. Therefore, applying the "bell curve" and choosing the appropriate score distribution requires flexibility from both instructors and educational administrators.

Applying assessment methods such as the bell curve is one of the effective solutions to control and minimize grade inflation. However, this needs to be done carefully and appropriately to the specific conditions of each school and each field of study.

Ultimately, the most important thing is to educate people about the meaning of grades and the true value of knowledge. Grades are not the ultimate goal of learning, but merely a means of measuring the entire learning process.

Author: Trinh Phuong Quan (Architect) holds a Master's degree in Civil and Environmental Engineering from Stanford University (USA). Prior to that, Quan studied sustainable design at the National University of Singapore and the Ho Chi Minh City University of Architecture. Quan is involved in architectural design and planning, and is also a contributing author to many newspapers, focusing on topics related to the environment, design, and culture.

The HIGHLIGHTS section welcomes your feedback on the article's content. Please go to the Comments section and share your thoughts. Thank you!

Source: https://dantri.com.vn/tam-diem/qua-nhieu-sinh-vien-kha-gioi-nen-thay-doi-cach-danh-gia-thang-diem-20241009214737040.htm

![[Image] Close-up of the newly discovered "sacred road" at My Son Sanctuary](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F13%2F1765587881240_ndo_br_ms5-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)