A shift in thinking about industrial policy

During the three decades following the end of the Cold War, global economic thinking was dominated by the “Washington Consensus” (1) – a set of economic policy principles that emphasized the role of free markets, privatization, and minimal state intervention in the economy. In this context, industrial policy – with the state’s intentional intervention in guiding the development of specific industries – was considered outdated, ineffective, and even harmful to economic development. International financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund regularly advised countries, especially developing countries, to avoid intervening in the market and let the “invisible hand” regulate the economy.

However, the global financial crisis of 2008 (2) created a significant turning point in economic policy thinking. The collapse of the financial system and the severe economic recession shook the confidence in the self-regulating ability of the market. Governments , even in the most strongly economic liberal countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, were forced to intervene extensively to save the financial system and strategic industries. It was from this point that discussions about the role of the state in the economy and the need for industrial policy began to return.

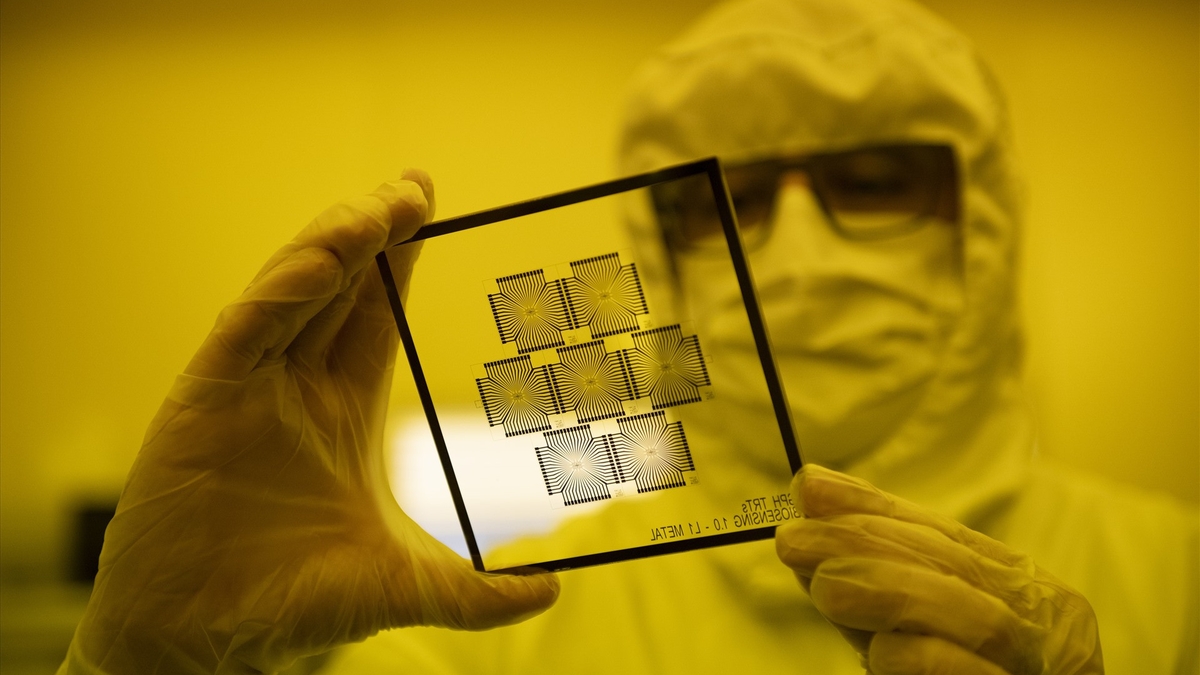

A series of global events and trends have strongly accelerated the return of industrial policy. First, the rapid rise of China with its “developmental state” model and strong government support for high-tech sectors such as 5G telecommunications, artificial intelligence and renewable energy has made Western countries concerned about losing their competitive advantage and lagging behind in developing emerging technologies. This has forced them to reconsider the role of the state in supporting domestic industrial development. Second , the COVID-19 pandemic that broke out in 2020 has caused serious disruptions in global supply chains, exposing the risks of over-reliance on a few suppliers, especially from China. The scarcity of essential medical products, semiconductors and many other important goods has made countries realize the importance of “strategic autonomy”, economic security and the need to build domestic production capacity for strategic products. Third , the challenge of climate change and the need for green transformation require huge investments and strategic direction from the state. The free market alone cannot create a strong enough driving force to promote the energy transition and develop green technologies at the pace needed to achieve global climate goals. The Fourth Industrial Revolution with the strong development of breakthrough digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), internet of things (IoT), cloud computing, quantum technology also requires large investments in basic and applied research.

The new industrial policy (3) has distinctly different characteristics compared to previous periods. Instead of focusing on “picking winners” – that is, selecting specific businesses or industries – modern industrial policy aims at “creating markets and ecosystems”, in other words, “supporting winners”. The State plays the role of a “venture capitalist”, willing to accept risks in investing in new technologies, while creating a favorable environment for innovation through building infrastructure, developing human resources, and setting technical standards. The new industrial policy is closely linked to the “great mission” of society, such as combating climate change, ensuring health security, and maintaining technological autonomy.

However, the return of industrial policy also poses significant risks. As countries compete to apply protectionist measures and subsidies to domestic industries, it could lead to the erosion of the multilateral trading system that has been built over decades. Industrial policy competition among major powers also risks turning into a trade and technology war, causing fragmentation of the global economy and reducing overall economic efficiency.

The industrial policy race of the great powers

Amid intensifying geopolitical and technological competition, major economies have launched industrial strategies of a scale and ambition not seen since the Cold War.

The United States has made a historic policy pivot under the Joe Biden administration. The CHIPS (4) and Science Act, passed in August 2022, marks the largest commitment by the US government to industrial policy in decades. The act allocates $52.7 billion in direct subsidies for the construction of semiconductor chip factories, along with huge investments in research and development. The goal is not only to reduce dependence on chip supplies from Asia, but also to restore the US's leadership in the semiconductor industry. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) (5) passed in the same year 2022 committed about $369 billion in investments and tax incentives to promote the development of clean energy technology and electric vehicle production. Notably, these incentives are designed with local content constraints, requiring products to be produced in North America or countries with free trade agreements with the United States to receive subsidies. This is a sophisticated form of protectionism, aimed at attracting global manufacturers to shift their supply chains to the United States and its allies. During the second term of President Trump's administration, industrial policy was clearly expressed through the reciprocal tariff policy, with the consistent goal of re-industrialization, bringing production back to the United States, especially in strategic industries and digital technology.

China, a pioneer in implementing large-scale industrial policies in recent decades, continues to promote the development-oriented state model. The Made in China 2025 Strategy (6) , announced in 2015, sets out the ambition to turn China into a high-tech manufacturing powerhouse, with the goal of self-sufficiency in 10 priority areas, including: new-generation information technology, high-end machine tools and robots, aerospace equipment, high-tech marine equipment, new energy vehicles, and biomedical equipment. To achieve this goal, China has mobilized huge resources through state investment funds, with the National Integrated Circuit Fund (National IC Fund) mobilizing more than 150 billion USD for the semiconductor industry. In addition to providing capital, the Chinese government also uses a range of other policy tools, such as preferential credit, direct subsidies for research and development, preferential public procurement for domestic products, and technology transfer requirements for foreign companies wanting to access the Chinese market. The dual circulation strategy launched in 2020 further emphasizes building technological self-sufficiency and reducing dependence on foreign supply chains.

The European Union (EU) has significantly adjusted its approach to industrial policy in recent years, moving from a skeptical to a proactive stance. The EU’s concept of open strategic autonomy reflects its desire to maintain openness to global trade while reducing dependence on external suppliers in strategic sectors. The European Chip Act (7) , adopted in 2023, aims to increase Europe’s share of semiconductor chip production from the current 10% to 20% by 2030, with a commitment to mobilize 43 billion euros from both public and private sources. The Green Deal Industrial Plan, announced in early 2023, is the EU’s direct response to the US Deinflation Act. It relaxes state subsidy rules, allowing member states to provide stronger support for clean technology projects. The EU also uses the Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) mechanism to fund cross-border industrial projects in areas such as electric batteries, green hydrogen, microelectronics. This allows for the pooling of resources between member states and avoids internal competition.

This industrial policy race is reshaping the structure of the global economy. The trend of “reshoring” (bringing production back home) and “friend-shoring” (8) (moving production to allied countries) has become popular, replacing the “offshoring” model (moving production abroad to take advantage of low costs) that has dominated for decades. This creates both opportunities and challenges for developing countries like Vietnam - opportunities from becoming a destination for capital flows, as well as challenges from fiercer competition and higher requirements for technological capacity.

Vietnam's Industrial Policy: Transformation of Thinking and Implementation Practice

From diffuse policy to focused strategy (9)

Vietnam's industrial development process over nearly 40 years of renovation has gone through many stages with different approaches.

Before 2021, although Vietnam had achieved significant achievements in economic development and industrialization, industrial policy still had many limitations. The approach was mainly scattered, lacking a comprehensive, synchronous strategy with a clear focus. Although our Party and State had issued many resolutions and policies on industrial development, there was no comprehensive thematic document on industrialization and modernization with a long-term vision and specific roadmap. The industrial development model in this period mainly relied on static comparative advantages, such as cheap labor, tax incentives, and attracting FDI in a wide range, without paying attention to quality and efficiency. As a result, Vietnam's industry grew rapidly in scale but remained at the level of processing and assembly with low added value, heavily dependent on imported raw materials and components. The localization rate in many important industries remains low, and domestic enterprises have not yet taken advantage of participating in the global value chain in high-value stages to absorb technology. The goal of becoming a modern industrialized country by 2020 has not been realized, reflecting the limitations in implementing industrial policies during this period.

The period from 2021 to present is a period marking an important turning point in Vietnam's thinking about industrial development. The 13th National Party Congress clearly identified the limitations of the previous development model and proposed a new direction, affirming that industrialization and modernization must be based on the foundation of science, technology, innovation and digital transformation. In particular, the 13th National Party Congress emphasized the need to build an independent and autonomous economy associated with deep and effective international integration - an important adjustment in the context of strategic competition and fragmentation of the global economy. This shift in thinking is comprehensively and specifically institutionalized by Resolution No. 29-NQ/TW, dated November 17, 2022, of the 13th Central Committee of the Party, on continuing to promote the country's industrialization and modernization to 2030, with a vision to 2045 (10) . This is the Party's first thematic resolution on industrialization and modernization, demonstrating the Party's special concern and strong determination to accelerate the country's industrialization and modernization process.

Resolution No. 29-NQ/TW - Foundation for new generation industrial policy (11) .

Resolution 29-NQ/TW has put forward breakthrough guiding viewpoints (12) , creating the foundation for a new generation of Vietnam's industrial policy, in line with international trends and the country's specific conditions. Firstly , the Resolution establishes science, technology, innovation and digital transformation as the main driving force of the new stage of industrialization, replacing the model based on cheap labor and investment capital. This shift reflects the awareness of the key role of technology in global competition and the determination to escape the middle-income trap. Secondly , the orientation of shifting from processing and assembly to mastering technology, designing and manufacturing finished products - from Made in Vietnam to Make in Vietnam - demonstrates the determination to upgrade the position in the global value chain, focusing on quality and the ability to master technology. Thirdly , in terms of resources, the Resolution establishes the principle: domestic resources are fundamental, strategic, and decisive; External resources are important and breakthrough. This approach balances between promoting internal resources and taking advantage of external resources, avoiding complete dependence on the outside. Fourth , the strategy focuses resources on three priority industries: foundational industries (metallurgy, basic chemicals, energy, mechanics); industries with competitive advantages (electronics, telecommunications, information technology, textiles, footwear); and spearhead industries (high technology, clean energy, digital industry).

Towards the strategic goals to 2030, with a vision to 2045, our Party and State have issued many important development policies, establishing the leading role of the state economy in orienting, regulating, stabilizing the macro-economy, pioneering in strategic sectors, enhancing the efficiency and leading role of state-owned enterprises, the private economy is the most important driving force, the collective economy and foreign investment economy play an important role in the economy. In the relationship between the above-mentioned economic sectors, industrial policy plays an important role as a tool of the State in connecting, creating connectivity, synchronization, and equality between economic sectors in the overall socialist-oriented market economy, contributing to establishing a new growth model with science, technology, innovation and digital transformation as the main driving force.

Issues facing Vietnam's economic diplomacy

The profound change in the international context with the industrial policy race between the great powers, along with the new strategic orientation in Vietnam's industrial policy, poses new requirements for economic diplomacy.

First, positioning Vietnam in the fragmented global industrial supply chain

In the context of the global supply chain undergoing a profound restructuring process, Vietnam has an important geostrategic and geoeconomic position. With a favorable foreign situation, Vietnam has the opportunity and capacity to participate in new supply chains that are taking shape.

The key issue for economic diplomacy is how to position Vietnam as a reliable, transparent and stable link in the global supply chain, promoting the role of a connecting country in the context of great power competition and increasing pressure to choose sides. This requires skillful balancing of interests with different partners, while building trust in the stability and predictability of the policy environment in Vietnam. Economic diplomacy needs to convey a clear message: Vietnam pursues a policy of multilateralization, diversification of economic relations, not dependent on any market or partner, deep integration coupled with improving the autonomy of the economy.

At the same time, Vietnam also needs to be vigilant against the risk of becoming the subject of trade defense measures (13) when countries increase protectionism in implementing industrial policies. The fact that some of Vietnam's export products are investigated for anti-dumping, anti-subsidy or subject to taxes due to concerns about transshipment of goods are existing challenges. Economic diplomacy must promote advocacy and exchanges with partners to clarify the origin (14) , make the supply chain transparent and convince about the real added value created in Vietnam.

Second, fierce competition in attracting high-tech FDI

The race to attract high-tech investment in Southeast Asia and Asia is becoming more fierce than ever. Vietnam's direct competitors, such as India, Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia, are all implementing drastic and attractive industrial policies. India with its Production Linked Incentive (PLI) program (15) worth tens of billions of USD, Indonesia with its downstream strategy in the mineral and battery industry (16) , Thailand with its ambition to become the electric vehicle manufacturing hub of Southeast Asia (17) - all pose great competitive challenges for Vietnam.

In this context, Vietnam's economic diplomacy cannot rely solely on traditional advantages such as low labor costs or tax incentives, but needs to build and promote new competitive advantages, including: Outstanding political stability; strong commitment to institutional reform and improving the business environment; potential for developing high-quality human resources with a young, dynamic, digitally skilled population; strategic geographical location and extensive FTA network; the determination of the entire political system in implementing breakthrough programs for science, technology and innovation development. In particular, it is necessary to emphasize Vietnam's commitment to protecting intellectual property rights and creating a favorable environment for research and development (R&D).

Economic diplomacy also needs to shift from a passive approach to actively inviting high-tech projects. This means not just waiting for investors to come and learn, but proactively approaching and persuading the world's leading technology corporations. It is necessary to build separate mechanisms and policies for each large potential investor, with incentives and support "tailored" to suit the specific needs of each corporation, in accordance with the capacity and actual conditions in the country.

Third, challenges in accessing core technology and developing human resources (18)

One of the biggest limitations of Vietnam's industrialization process is the limited transfer of technology from FDI projects. Technology transfer from FDI to Vietnam is still weak because most projects only stop at low-tech processing and assembly, with little on-site R&D. FDI enterprises and domestic enterprises lack linkages, making it difficult for Vietnamese enterprises to access and learn technology. In the new context, economic diplomacy needs to change its role from "inviting investment" to "negotiating technology". This requires the economic diplomacy team to have a deep understanding of technology, development trends of industries, and the ability to negotiate terms on technology transfer, R&D, and human resource training. It is necessary to build effective binding mechanisms, such as requiring a certain proportion of R&D to be performed in Vietnam, the number of Vietnamese engineers and scientists recruited, or commitments on technology transfer to domestic partners.

At the same time, the issue of developing high-quality human resources is also a big challenge. Vietnam is seriously lacking highly skilled human resources in key technology fields. Economic diplomacy needs to play a bridging role to attract training cooperation programs with developed countries and large technology corporations. There needs to be an educational diplomacy strategy to attract the world's leading universities and research institutes to Vietnam, while creating conditions for Vietnamese students and postgraduates to be trained at the best facilities in the world.

Fourth, adapting to new rules and standards in international trade (19)

The international trade picture is increasingly complex with the emergence of new generation non-tariff barriers. The EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) will impose carbon taxes on a number of imported products. Laws on forced labor, traceability, circular economy, etc. are being applied more and more strictly by developed countries. These new rules of the game are both challenges and opportunities for Vietnam. Economic diplomacy must play the role of early warning and guidance for Vietnamese businesses. It is necessary to closely monitor new policy moves of trade partners, analyze impacts and provide timely information to businesses. At the same time, it is necessary to proactively participate in the process of building international standards, ensuring that the voices of Vietnam and developing countries are heard, avoiding the situation where standards are designed in a one-sided way to benefit developed countries.

Some recommendations to improve the effectiveness of economic diplomacy

Faced with these challenges and opportunities, Vietnam's economic diplomacy needs to make fundamental strategic adjustments to effectively serve the goals of industrialization and modernization in the new period.

First, shift the focus of economic diplomacy from broad to deep, using quality as a measure of effectiveness.

In the previous period, Vietnam's economic diplomacy mainly focused on expanding relations, signing many agreements, and attracting large amounts of FDI. This approach brought important results, helping Vietnam integrate deeply into the world economy. However, in the new context, it is necessary to shift to depth, focusing on quality and real effectiveness. The effectiveness of economic diplomacy should not be measured only by the number of signed MOUs, licensed FDI projects, or trade turnover. Instead, it should be evaluated by quality criteria, such as: The level of real technology transfer; the number of high-quality jobs created; the localization rate in projects; the number of Vietnamese enterprises participating in the supply chains of multinational corporations; the amount of spending on R&D in Vietnam; the number of patents registered. These are the indicators that truly reflect the quality of the industrialization process. To carry out this transformation, it is necessary to build a new performance evaluation system for economic diplomacy, with clear quantitative indicators linked to quality goals. Vietnamese representative agencies abroad need to be assigned specific tasks not only in terms of quantity but more importantly in terms of the quality of projects and the depth of cooperation relationships established and strengthened.

Second, improve the capacity and initiative of the apparatus implementing economic diplomacy (20)

The new requirements of economic diplomacy require fundamental innovation in the organization and capacity of the implementation apparatus. Vietnamese representative agencies abroad need to reposition their roles, from mainly traditional political-diplomatic representation to becoming centers of economic-technological information. This requires strengthening the team of counselors and experts with in-depth expertise in economics, trade, science and technology to collect information, increase the ability to analyze trends, forecast opportunities and challenges, and effectively connect foreign partners with domestic enterprises and agencies. It is necessary to promote the application of digital technology in economic diplomacy. Build a digital platform to connect information between representative agencies and domestic enterprises; build and operate a database system on partners, markets, and technology; use artificial intelligence to analyze trends and forecast opportunities. Technological diplomacy is not only a support tool but also needs to become an important channel to promote national image and attract investment.

The return of industrial policy on a global scale is reshaping the world economic order and the rules of the international economic game. This is an inevitable trend reflecting profound changes in the global power structure, technological progress and common challenges of humanity. For Vietnam, this context poses enormous challenges but also opens up a historic opportunity to make a transformation in the process of industrialization and modernization.

In the era of global industrial competition, economic diplomacy is no longer just a supporting activity but has become a key driving force of the national industrialization strategy. With a proactive, creative, and effective economic diplomacy, harmoniously combining promoting internal strength and taking advantage of external strength, Vietnam can completely overcome challenges and take advantage of opportunities to realize its aspiration to become a developed, high-income industrialized country by 2045./.

------------------------

(1) Reda Cherif, Fuad Hasanov: “The Return of the Policy That Shall Not Be Named: Principles of Industrial Policy”, IMF Working Paper WP/19/74, March 2019, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/03/26/The-Return-of-the-Policy-That-Shall-Not-Be-Named-Principles-of-Industrial-Policy-46710

(2) Mariana Mazzucato: “Policy with a Purpose – Modern industrial policy should shape markets, not just fix their failures ” , Finance & Development Magazine (IMF) , September 2024, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2024/09/policy-with-a-purpose-mazucato

(3) Anna Ilyina, Ceyla Pazarbasioglu & Michele Ruta: “Industrial Policy is Back. Is That a Good Thing?”, IMF/Econofact , October 21, 2024, https://econofact.org/industrial-policy-is-back-is-that-a-good-thing

(4) Reuters: “Biden signs CHIPS and Science Act, allocating $52.7 billion to semiconductor manufacturing and R&D, ” August 9, 2022, https://www.trendforce.com/news/2025/06/05/news-trump-administration-reportedly-reconsiders-chips-act-subsidies-touts-tsmc-as-model

(5) Vu Phong News: “US issues new law for energy security and climate change prevention” , August 17, 2022, https://vuphong.vn/my-ban-hanh-luat-moi-cho-an-ninh-nang-luong-chong-bien-doi-khi-hau

(6) Jinran Chen , Lijuan

(7) EU Commission: “European Chips Act – Q&A”, September 21, 2023, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/european-chips-act_en

(8) Anna Ilyina, Ceyla Pazarbasioglu & Michele Ruta: “Industrial Policy is Back. Is That a Good Thing?”, IMF/Econofact , October 21, 2024, https://econofact.org/industrial-policy-is-back-is-that-a-good-thing

(9) Tran Tuan Anh: Speech on Resolution 29 at the 6th Central Conference, Session XIII, Government Electronic Newspaper , December 6, 2022, https://baochinhphu.vn/nghi-quyet-29-co-5-nhom-quan-diem-chi-dao-toan-dien-ve-cnh-hdh-102221205210956811.htm

(10) Tran Tuan Anh: Speech on Resolution 29 at the 6th Central Conference, Session XIII, Government Electronic Newspaper , December 6, 2022, https://baochinhphu.vn/nghi-quyet-29-co-5-nhom-quan-diem-chi-dao-toan-dien-ve-cnh-hdh-102221205210956811.htm

(11) Tran Tuan Anh: Speech on Resolution 29 at the 6th Central Conference, Session XIII, Government Electronic Newspaper , December 6, 2022, https://baochinhphu.vn/nghi-quyet-29-co-5-nhom-quan-diem-chi-dao-toan-dien-ve-cnh-hdh-102221205210956811.htm

(12) Tran Tuan Anh: Speech on Resolution 29 at the 6th Central Conference, Session XIII, Government Electronic Newspaper , December 6, 2022, https://baochinhphu.vn/nghi-quyet-29-co-5-nhom-quan-diem-chi-dao-toan-dien-ve-cnh-hdh-102221205210956811.htm

(13) Quoted from Phuc Long/Tuoi Tre Newspaper: “US imposes heavy tax on Vietnamese steel originating from China”, VOV , December 7, 2017, https://vov.vn/kinh-te/my-danh-thue-nang-len-thep-viet-nam-xuat-xu-trung-quoc-704348.vov

(14) Huyen My: “The United States initiated an anti-dumping/anti-subsidy investigation into Vietnamese hardwood and decorative plywood ” , Industry and Trade Magazine , June 23, 2025, https://tapchicongthuong.vn/hoa-ky-chinh-thuc-khoi-xuong-dieu-tra-chong-ban-pha-gia-chong-tro-cap-voi-go-dan-cung-va-trang-tri-viet-nam-141986.htm

(15) Press Trust of India/PIB: “Government scales up PLI budget to over US$26 billion for 14 sectors”, 2021, https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2107825

(16) Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada: “Indonesia as an Emerging Hub for Critical Minerals and Electric Vehicles: Opportunities and Risks for Canada”, February 2024, https://www.asiapacific.ca/sites/default/files/publication-pdf/IM_Indonesia_EN_Final.pdf

(17) Reuters: “Thailand adjusts EV policy to ease production requirements, exports target”, July 30, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/en/thailand-adjusts-ev-policy-ease-production-requirements-target-exports-2025-07-30/

(18) Nguyen Van Lich - Tran Hong Anh: "Economic diplomacy: Current situation and solutions to promote" , Electronic Communist Magazine , September 12, 2025, https://tapchicongsan.org.vn/web/guest/quoc-phong-an-ninh-oi-ngoai1/-/2018/1131102/cong-tac-ngoai-giao-kinh-te--thuc-trang-va-giai-phap-thuc-day.aspx

(19) Nguyen Van Lich - Tran Hong Anh: "Economic diplomacy: Current situation and solutions to promote" , Electronic Communist Magazine , September 12, 2025, https://tapchicongsan.org.vn/web/guest/quoc-phong-an-ninh-oi-ngoai1/-/2018/1131102/cong-tac-ngoai-giao-kinh-te--thuc-trang-va-giai-phap-thuc-day.aspx

(20) Resolution No. 41-NQ/TW, dated October 30, 2023, of the Politburo, "On building and promoting the role of Vietnamese entrepreneurs in the new period"

Source: https://tapchicongsan.org.vn/web/guest/kinh-te/-/2018/1161902/chinh-sach-cong-nghiep-trong-boi-canh-canh-tranh--cong-nghe-giua-cac-nen-kinh-te-lon-va-ham-y-cho-cong-toc-ngoai-giao-kinh-te-cua-viet-nam.aspx

![[Photo] Da Nang: Hundreds of people join hands to clean up a vital tourist route after storm No. 13](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/11/07/1762491638903_image-3-1353-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)