Writer Nguyen Chi Trung, the "boss" of this writing camp, sent a letter to the General Political Department requesting my return to the camp. It was the letter I had been waiting for, and I could hardly believe I had received it.

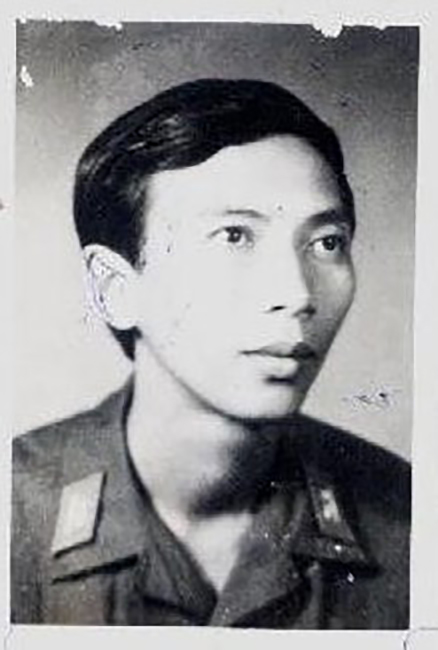

Poet and Lieutenant Thanh Thảo - 1976

Upon arriving in Da Nang , officially becoming a member of the largest and first literary writing camp in the country, I was overjoyed, because I had been harboring a longing to write an epic poem but hadn't had the opportunity. Now, the opportunity had arrived.

I signed up directly with Mr. Nguyen Chi Trung, stating that I would write an epic poem about the war. Actually, while on the battlefield in Southern Vietnam, I had already written over 100 verses, which I called "sketches" for this future epic. Then I tentatively titled my first epic poem " Months and Moments ."

In late May 1975, I traveled from Saigon with a group of writers from Central Vietnam, including Nguyen Ngoc, Nguyen Chi Trung, Thu Bon, Y Nhi, and Ngo The Oanh, to Da Lat before returning to Central Vietnam. There, I had the opportunity to attend a "sleepless night" with student activists. During that gathering, when asked to read poetry, I chose to recite nearly a hundred lines from my manuscript , "Months and Moments ." That was the first time I had read my own poetry to urban students in Southern Vietnam. It was quite moving.

Then, when I finally had some free time to sit down at my writing desk at the Military Region 5 Creative Writing Camp—something I had long dreamed of—a suggestion suddenly came to me from my subconscious. I remembered Van Cao's epic poem , "People on the Seaport ." I had read this epic poem in Hanoi before going to the Southern battlefield. It was Van Cao's title , "People on the Seaport, " that gave me the idea: I could change the title of my epic poem to "People Going to the Sea ." It sounded more logical. Thus, from "Months and Moments" became "People Going to the Sea ." Why "People Going to the Sea" ? I think our generation participated in the war consciously; therefore, "going to the sea" meant going to our people. The people are the sea, something Nguyen Trai said hundreds of years ago.

Since changing the title of my epic poem, I feel more at ease writing, as if I'm a tiny leaf meeting a river and drifting out to sea.

1976 was my "Year of the Fire," yet I managed to plan and essentially accomplish significant things that year. First, there was the writing of my epic poem. Then came love. The girl I loved, who loved me, accepted to spend her life with a poor soldier and poet—me. I introduced her to my parents, and they joyfully approved.

There was only one thing that I couldn't have predicted. That was in 1976, when I was promoted from lieutenant to captain. I was overjoyed by this promotion. From then on, my salary increased from 65 dong (lieutenant's salary) to 75 dong (captain's salary). Only those who lived through that time can understand how important an extra 10 dong in salary each month was. I knew all too well how difficult it was to constantly be short of money. There were times when I had to ask my girlfriend for 5 cents to buy a cup of tea at a street stall.

Moreover, when I was a poet and lieutenant, I immediately remembered how wonderful the works of Soviet writers and poets after the Great Patriotic War were, all of whom were lieutenants in the Red Army. That extra ten dollars in salary upon promotion to lieutenant served as both a material and a morale boost.

Then all that remained was to focus on writing the epic poem "Those Who Go to the Sea" .

At the end of 1976, I completed this epic poem. When I read it to my "boss," Nguyen Chi Trung, for his review, I received a nod of approval from a very demanding and meticulous writer. Mr. Trung only told me to change one word. It was the word "rạn" (cracked) in the line "The nine-year-old bamboo carrying pole is cracked on both shoulders," from Nguyen Du's poem. Mr. Trung said it should be "dạn" (hardened) instead, "The nine-year-old bamboo carrying pole is hardened on both shoulders." I immediately agreed. Indeed, my "boss" was different; he was absolutely right.

Having finished writing my epic poem of over 1,200 verses, I was so happy that I invited poet Thu Bồn to listen, accompanied by wine and snacks. Thu Bồn listened with emotion, and when I read the lines: "Please, Mother, keep chewing betel nut for a peaceful afternoon / Before that smile fades, the crescent moon will become full again," he burst into tears. He remembered his mother, the mother who had waited for him throughout the war.

After writer Nguyen Chi Trung approved my epic poem, he had it typed up and sent it immediately to the Army Publishing House. At that time, the poetry editor for this publishing house was poet Ta Huu Yen, a former colleague of mine who had worked with me in the propaganda department of the Army before I went to the battlefield. Mr. Yen immediately agreed to edit it. At the same time, writer Nguyen Ngoc, who was on the leadership board of the Vietnam Writers Association, heard rumors about the epic poem " Those Who Go to the Sea " and asked Mr. Ta Huu Yen to lend him the manuscript to read. It turned out that after reading it, Mr. Nguyen Ngoc told the Army Publishing House to print the epic poem immediately. And so, from the time the work was sent to the publishing house until the book was printed, it only took three months. That was a record for "fast publishing" at the time.

After the Lunar New Year in 1977, I held my wedding in Hanoi and received the news that my first work had just been printed. The paper was of poor quality back then, but the cover was drawn by the artist Dinh Cuong. I was overjoyed.

Now, The Seafarers are 47 years old. In three years, in 2027, they will be exactly 50 years old.

Rereading my first epic poem, I feel that its greatest strength lies in its purity. From the very first four lines:

"When the child speaks to the mother"

The rain falls, blurring our fields.

I'm leaving tomorrow.

The smoke from the kitchen fire suddenly stopped rising above the thatched roof where mother and daughter were.

up to the last four lines of the epic poem:

" when I scooped up the salty water in my hand"

That's when I met you in my life.

Under the sun, it is slowly crystallizing.

"Tiny grains of salt, innocent and pure"

Complete purity.

My five years of living and fighting on the battlefield were not in vain. They are the most valuable asset of my life. Even now, as I'm about to turn 80.

Source: https://thanhnien.vn/truong-ca-dau-tien-cua-toi-185250107225542478.htm

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh attends the Conference summarizing and implementing tasks of the judicial sector.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F13%2F1765616082148_dsc-5565-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)