|

Chip manufacturing – a global technological competition.

For modern industries, chips play a crucial role. This was particularly evident during the recent Covid-19 pandemic. Due to a shortage of electronic components, global car production fell by a quarter in 2021, as chip manufacturers had previously focused on household appliances, computers, phones, and electric vehicles.

For Russian industries, the chip shortage was particularly severe in 2022, when foreign chip manufacturers successively refused to supply. Russian car production stalled for several months due to a shortage of ABS (Anti-Lock Brake System) control units and airbags. The situation improved somewhat with the launch of domestic ABS production in the city of Kaluga Itelma under license from China. But the most difficult part of the product, the electronic brain of the control unit, is readily available from China. Creating its own ABS system would require more than a year and over a billion dollars in investment. Russia is now forced to pay such a price for decades of neglect. The automotive industry is just one example among countless production chains where Russia is forced to rely on imported chips and components.

Self-reliance in the microelectronics industry depends on many factors, both internal and external. Restrictions on the import of high-tech semiconductors are not only aimed at Russia but also at China. The Dutch company ASM Lithography, which produces the world's most advanced lithography machines (chip manufacturing machines), has been banned by the United States from selling its products to China. Since August 2022, the US has had the CHIPS Act (Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors Act), or Semiconductor Production Incentives Act. The main goal is to shift some of the production of microchips back to the United States. Currently, the US produces 70-75% of its semiconductors in Taiwan (China). The CHIPS Act plans to invest $52 billion in developing manufacturing in the US and over $24 billion in related tax incentives.

Furthermore, the US is considering a ban on supplying Russia and China with advanced graphics processors from Nvidia, used in the manufacture of supercomputers. According to US calculations, this would slow the development of artificial intelligence technology in these two rivals. In March 2023, the CHIPS Act further tightened restrictions on China. A ban was issued on investments in the production of chips with a topology smaller than 28 nanometers in China. In response and to protect national security and interests, Beijing imposed export controls on gallium and germanium, widely used in microelectronics manufacturing, starting August 1st of this year. China currently produces about 80% of the world's gallium and 60% of its germanium.

|

Lessons from countries striving for chip self-sufficiency.

In 2015, the Chinese government announced the "Made in China 2025" concept, aiming for the country to meet over 70% of its domestic semiconductor needs by 2025. However, by 2022, that figure had fallen to just 16%. The project has failed despite China being in a much more advantageous position than Russia is now.

Even for India, a country with a relatively high level of information technology, developing its own chip technology is challenging. To organize domestic chip production, India invited Foxconn of Taiwan (China). Initially, they aimed for a 28 nm chip manufacturing standard, later lowering it to 40 nm, but ultimately, Taiwan (China) withdrew from the project. Many reasons could have been cited, but the main one was the inability to find a highly skilled technical team in India for manufacturing.

Russia has no intention of staying out of the global chip war, albeit rather late. Currently, Russia can produce chips with a topology of at least 65 nm or higher, while TSMC of Taiwan (China) has mastered 5 nm.

One question that arises in the current Russia-Ukraine conflict is why Russia can launch missiles and other weapons so seemingly endlessly. The answer is that the chips for missiles and other military equipment can be manufactured with a 100-150nm topology, a type that Russia can proactively produce. Russia manufactures 65nm chips exclusively on imported equipment under license, such as used Nikon and ASM Lithography chips.

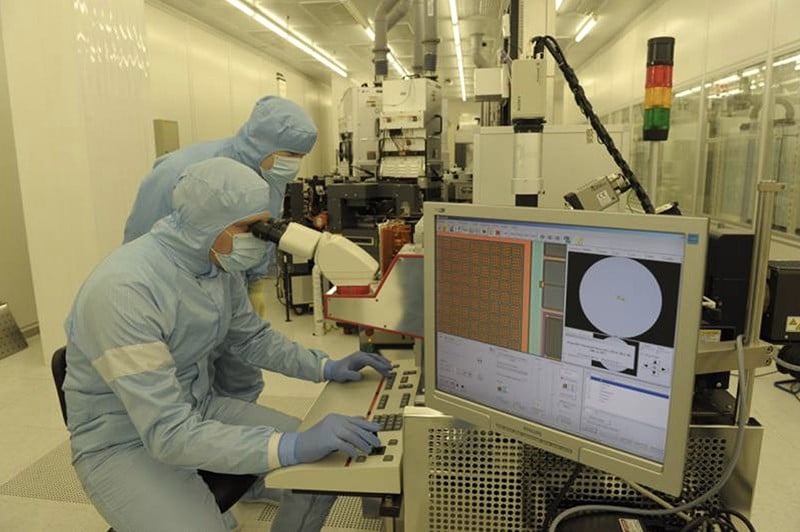

Regarding consumer chip production projects, Russia has taken some initial steps. A 28-nanometer topology chip manufacturing plant is under construction in Zelenograd, and Mikron has received a 7 billion ruble loan (approximately $100 million) to expand production. Additionally, the Zelenograd Nanotechnology Center is developing a 5.7 billion ruble ($70 million) contract for a 130 nm lithography machine. Nearly one billion rubles has been allocated to the center for manufacturing a 350 nm topology machine. The technology is clearly old, but it is entirely domestically produced. Five billion rubles have been allocated to building a network of test sites for producing developed chips, such as at the Moscow Institute of Electronic Technology, in St. Petersburg, and other Russian cities.

But money isn't everything. The difficulties for the chip self-sufficiency program aren't limited to the complexity of the product; there are other issues as well. First is the shortage of engineers. Hundreds of billions of rubles can be allocated to priority programs, but it's impossible to find highly qualified specialists. Creating world-class semiconductors requires the efforts of hundreds, if not thousands, of engineers and scientists. And not from a single institute or design company, but from entire corporations. According to the Kommersant newspaper, in July 2023, 42% of Russian industrial facilities faced labor shortages. Kronstadt, a well-known drone manufacturer, couldn't find workers in nine specialties simultaneously, including key personnel such as operational and testing engineers, process engineers, aircraft assemblers, and aircraft electrical equipment installers. This problem could now get even worse. So the question is, where will we find workers for future microchip manufacturing plants?

Next comes the challenge of transferring laboratory results to mass production. For example, the Institute of Microstructure Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences has long been quite successful in researching EUV lithography machines. These are modern machines that operate based on X-rays and are capable of manufacturing chips with a structure of 10 nm or less. In 2019, the Institute's chief expert, Honorary Academician Nikolai Salashchenko, stated that Russia was researching the development of a lithography machine that would be ten times cheaper than existing foreign equipment and hoped that this machine could be perfected within five to six years. It would be a highly anticipated machine for creating ultra-small chips and capable of small-scale production.

It's ambitious, but in reality, after almost five years, there's still no news about a breakthrough in lithographic printing technology. Even if scientists create a prototype, they still need to develop a production process and then build a factory. In theory, Russia could develop a perfect prototype lithographic printer, better than any product from Nikon and ASM Lithography, but failed in large-scale production. This wasn't uncommon during the Soviet era and remains a problem today.

Source

![[Image] Fifth meeting of the Steering Committee for National Projects in the Railway Sector](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F06%2F1767712857541_ndo_br_dsc-0581-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh attends the Conference on the Implementation of Tasks for the Finance Sector in 2026](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F06%2F1767699638245_ndo_br_dsc-0196-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh receives Canadian Minister of International Development Randeep Sarai](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2026%2F01%2F06%2F1767708661052_image123-3433-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)