Experts believe the devastating wildfires in Hawaii are the result of a combination of factors that have long existed in the archipelago and have precedents.

After winds from a hurricane caused wildfires to spread across the Hawaiian Islands in 2018, researchers scoured the scientific literature for similar disasters. They found two.

Now, hurricane-fueled wildfires are once again burning through the state, killing at least 80 people and leaving the historic town of Lahaina almost completely destroyed.

Scientists and wildfire activists say Hawaii's fires have been amplified by multiple factors and more disasters are likely in the future.

Elizabeth Pickett, co-director of the Hawaii Wildfire Response Organization, said that while the fires of the past week have taken many by surprise, they were not entirely unexpected. Despite its rainforests and waterfalls, Hawaii is a hot place, and temperatures are rising.

"We couldn't adjust everything, but this disaster was predictable," she said.

Smoke rises from wildfires in Hawaii on August 10. Photo: AFP

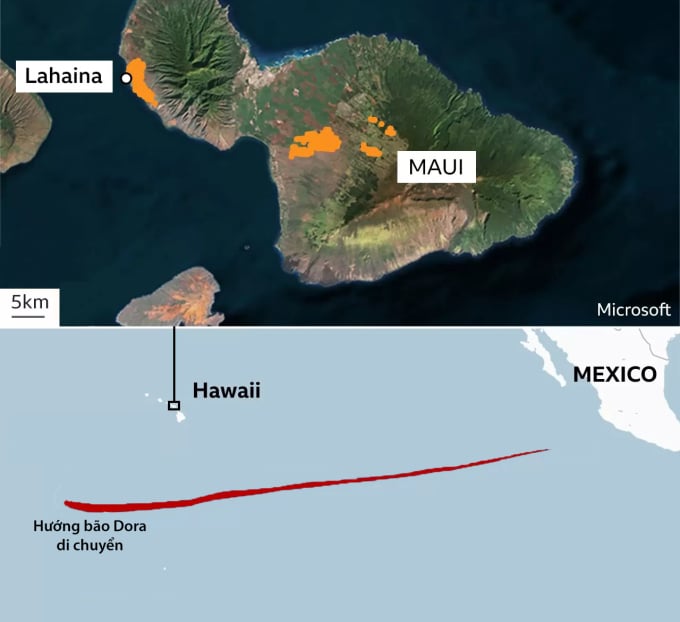

The fires began spreading across Maui, Oahu and the Big Island of Hawaii on August 8, when the National Weather Service issued a red alert. Much of the state has been experiencing months of drought, especially the area surrounding the town of Lahaina.

That means even a small spark can quickly ignite a fire in vegetation already parched by the heat. And fueled by winds, the flames can spread toward residential communities.

Strong winds are common in Hawaii. Even in typical summer weather, wind speeds can reach 65 km/h. But the winds that swept across the islands and fueled wildfires last week were particularly strong, with gusts exceeding 130 km/h on both the Big Island and Oahu, and reaching nearly 108 km/h on Maui, according to data from the National Weather Service.

Some Hawaii officials admitted the extent of the fires caught them by surprise. "We did not expect that a hurricane that did not impact our islands could cause such devastating wildfires," said Lieutenant Governor Josh Green.

Location of Maui island and the path of Hurricane Dora. Graphic: BBC

The winds are believed to be the product of a difference in atmospheric pressure between an area of high pressure in the North Pacific and low pressure at the center of Hurricane Dora, which was hundreds of kilometers south of the Hawaiian Islands on August 8.

Alison Nugent, a meteorologist from the University of Hawaii, said that even without Hurricane Dora, the impact of normal winds, which are relatively dry and blow along the slopes of Hawaii, would have been enough to cause the fires to flare up intensely. But according to her, Hurricane Dora contributed to the increased wind intensity.

Similar scenarios occurred in two examples the researchers found. In 2007, a tropical storm caused smoldering wildfires in Florida and Georgia to flare up intensely. A decade later, wildfires across Portugal and Spain killed more than 30 people when a storm swept across the coasts of those two countries.

Nugent said there is every reason for scientists to worry that future hurricanes, while rarely making direct landfall in Hawaii but rather passing over it, could still cause serious damage to the islands.

While there is no clear link between human-caused climate change and drought in Hawaii, the general trend across the region is decreasing rainfall and increasing the number of consecutive dry days.

Ian Morrison, a meteorologist in Honolulu, Hawaii, said this year's rainy season brought below-average rainfall, meaning the weather became unusually dry as summer entered.

One factor increasing the risk of wildfires in Hawaii is the growth of non-native, flammable grasses. Like much of the rest of the archipelago, Maui's native vegetation has been replaced by sugar and pineapple plantations and cattle ranching. However, in recent decades, agricultural activity has declined significantly.

Nugent's research shows that before Hurricane Lane struck in 2018, 60% of the land previously used for farming and livestock in Hawaii had been abandoned. This land was then overgrown with flammable grasses such as lemongrass or pampas grass, which had been brought to the islands to cover barren pastures and for ornamental purposes.

Both species are adapted to thrive after fires, creating more fuel for subsequent fires and crowding out native plants.

"It's like throwing a ton of weeds into your backyard and then planting some really fragile plants in between," says Lisa Ellsworth, an associate professor at Oregon State University who has studied invasive weeds in Hawaii. "It's a cycle that creates more invasive weeds and more wildfires."

Researchers found that non-native flammable grass and shrublands accounted for more than 85 percent of the area burned in the 2018 Hurricane Lane wildfires. Local fire agencies estimate such areas now cover about a quarter of Hawaii.

Wildfires ravage a resort town in Hawaii. Video: Reuters, AFP

These vegetation patches often run along densely populated areas with valuable real estate, so Pickett says significant government investment and new policies are needed to help communities like these better prepare for the fire risks they face.

In addition to material damage and loss of life, the effects of wildfires also damage the landscape of Hawaii in the long term.

Unlike the western United States, where moderate fires can improve forest health (recycling essential nutrients for plants), Hawaii's ecosystems are not adapted to coexist with wildfires, assesses Melissa Chimera, coordinator from the wildfire prevention organization Pacific Fire Exchange.

The burned native flora is replaced by invasive species instead of growing back. A 2007 fire destroyed almost all of the yellow hibiscus, Hawaii’s state flower, on the island of Oahu.

On the other hand, rain can also wash fire debris into the ocean, suffocating coral and degrading water quality.

"For the ecosystem of the area, fire has no effect whatsoever," Chimera said. "Absolutely none."

Vu Hoang (According to Washington Post )

Source link

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh holds a phone call with the CEO of Russia's Rosatom Corporation.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F11%2F1765464552365_dsc-5295-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] Closing Ceremony of the 10th Session of the 15th National Assembly](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F11%2F1765448959967_image-1437-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[OFFICIAL] MISA GROUP ANNOUNCES ITS PIONEERING BRAND POSITIONING IN BUILDING AGENTIC AI FOR BUSINESSES, HOUSEHOLDS, AND THE GOVERNMENT](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/12/11/1765444754256_agentic-ai_postfb-scaled.png)

Comment (0)