In the 14th century, an alchemist made an astonishing discovery . Mixing nitric acid with ammonium chloride (then known as sal ammoniac) produced a fuming, highly corrosive solution that could dissolve gold, platinum, and other precious metals. This solution became known as aqua regia or "royal water."

This is considered a major breakthrough in the quest to discover the Philosopher's Stone – a mythical substance believed to be capable of creating an elixir of immortality and transforming base metals like lead into gold.

Freshly prepared aqua regia. (Image: Wikipedia)

Although alchemists ultimately failed in this endeavor, aqua regia (now produced by mixing nitric acid and hydrochloric acid) is still used for etching metals, cleaning metal stains and organic compounds from laboratory glassware. It is also used in the Wohlwill Process to refine gold to 99.999% purity.

In a bizarre turn of events during World War II, this corrosive liquid was used in an even more dramatic instance, helping a chemist save his colleague's scientific legacy from the Nazis.

In the late 1930s, Nazi Germany desperately needed gold to fund its upcoming war of aggression. To achieve this goal, the Nazis banned the export of gold and, along with the ongoing persecution of Jews, German soldiers confiscated large quantities of gold and other valuables from Jewish families and other persecuted groups.

Among the confiscated items were Nobel Prize medals won by German scientists. Many of them had been dismissed from their positions in 1933 because of their Jewish ancestry.

A Nobel gold medal. (Photo: AFP)

After journalist and pacifist Carl von Ossietzky, while imprisoned, received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1935, the Nazi regime banned all Germans from accepting or holding any Nobel Prizes.

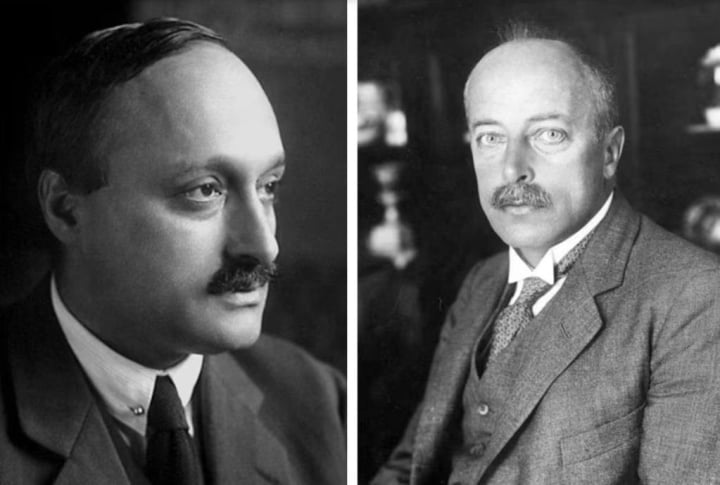

Among the German scientists affected by the ban were Max von Laue and James Franck. Von Laue received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914 for his work on X-ray diffraction in crystals, while Franck and his colleague Gustav Hertz received the award in 1925 for confirming the quantum nature of the electron.

In December 1933, von Laue, who was Jewish, was dismissed from his position as advisor at the Federal Institute of Physics and Technology in Braunschweig under the newly enacted Law on the Restoration of Professional Civil Service. Franck, although exempt from this law due to his previous military service, resigned from the University of Göttingen in protest in April 1933.

Along with fellow physicist Otto Hahn, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1944 for his discovery of nuclear fission, von Laue and Franck helped dozens of persecuted colleagues emigrate from Germany during the 1930s and 1940s.

Unwilling to have their Nobel medals confiscated by the Nazis, von Laue and Franck sent them to the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, who had won the 1922 Nobel Prize in Physics, for safekeeping. The Institute of Physics that Bohr founded in Copenhagen had long been a safe haven for refugees fleeing Nazi persecution. The institute worked closely with the American Rockefeller Foundation to find temporary jobs for German scientists. But on April 9, 1940, everything changed when Adolf Hitler invaded Denmark.

As the German army marched through Copenhagen and approached the Institute of Physics, Bohr and his colleagues faced a dilemma. If the Nazis discovered Franck and von Laue's Nobel medals, the two scientists would be arrested and executed. Unfortunately, these medals were not easy to conceal because they were heavier and larger than modern-day Nobel medals. The names of the winners were also prominently engraved on the back, making the medals nothing less than solid gold death warrants for Franck and von Laue.

In desperation, Bohr turned to George de Hevesy, a Hungarian chemist working in his laboratory. In 1922, de Hevesy had discovered the element hafnium and subsequently pioneered the use of radioactive isotopes as markers to track biological processes in plants and animals – work for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1943. Initially, de Hevesy suggested burying the medals, but Bohr immediately rejected this idea, knowing that the German army would certainly dig up the grounds of the Institute of Physics in search of them. Therefore, De Hevesy proposed a solution: dissolve the medals in aqua regia.

Aqua regia can dissolve gold because it combines both nitric acid and hydrochloric acid, whereas neither chemical alone can do this. Nitric acid can usually oxidize gold, producing gold ions, but the solution quickly becomes saturated, causing the reaction to stop.

When hydrochloric acid is added to nitric acid, the resulting reaction forms nitrosyl chloride and chlorine gas, both of which are volatile and escape from the solution as vapor. The more of these products that escape, the less effective the mixture becomes, meaning that aqua regia must be prepared immediately before use. When gold is immersed in this mixture, the nitrosyl chloride will oxidize the gold.

However, the chloride ions in hydrochloric acid will react with the gold ions, producing chloroauric acid. This removes the gold from the solution, preventing it from becoming saturated and allowing the reaction to continue.

Max von Laue and James Franck – two Nobel laureates whose bodies were melted down to deceive the Nazis. (Image: Wikimedia Commons)

But although this method was effective, the process was very slow, meaning that after de Hevesy had dipped the medals into a cup of aqua regia, he had to wait for long hours for them to dissolve. Meanwhile, the Germans were closer than ever.

However, eventually, the gold medals disappeared, the solution in the cup turned pink and then dark orange.

The work was done, and de Hevesy then placed the glass beaker on a laboratory shelf, hiding it among dozens of other brightly colored chemical beakers. Amazingly, the trick worked. Although the Germans searched the Institute of Physics from top to bottom, they never suspected the beaker containing the orange liquid on de Hevesy's shelf. They believed it was just another harmless chemical solution.

George de Hevesy, who was Jewish, remained in Copenhagen – a Nazi-occupied city – until 1943, but was eventually forced to flee to Stockholm. Upon arriving in Sweden, he was informed that he had won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. With the help of Hans von Euler-Chelpin, the Swedish Nobel laureate, de Hevesy found a position at Stockholm University, where he remained until 1961.

Upon returning to his Copenhagen laboratory, de Hevesy found the vial of aqua regia containing the dissolved Nobel medals exactly where he had left them, intact on the shelf. Using iron chloride, de Hevesy extracted the gold from the solution and gave it to the Nobel Foundation in Sweden. The foundation used the gold to recast Franck and von Laue's medals. The medals were returned to their original owners in a ceremony at the University of Chicago on January 31, 1952.

Although dissolving the gold medal was a small act, George de Hevesy's clever action was one of countless acts of resistance against Nazi Germany that helped ensure the ultimate victory of the Allies and led to the collapse of fascism in Europe.

Although aqua regia is often considered the only chemical that can dissolve gold, this isn't entirely accurate, as there's another element: the liquid metal mercury. When mixed with almost all metals, mercury penetrates and blends into their crystal structure, forming a solid or paste-like substance called an amalgam.

This process is also used in the extraction and refining of silver and gold from ore. In this process, crushed ore is mixed with liquid mercury, causing the gold or silver within the ore to seep out and mix with the mercury. The mercury is then heated to evaporate, leaving the pure metal.

(Source: News Report/todayifoundout)

Beneficial

Emotion

Creative

Unique

Source

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh holds a phone call with the CEO of Russia's Rosatom Corporation.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F11%2F1765464552365_dsc-5295-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] Closing Ceremony of the 10th Session of the 15th National Assembly](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F11%2F1765448959967_image-1437-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)