It seems that, for the inhabitants of the Mekong Delta, the flood season is a special season; it is neither spring, summer, autumn, nor winter, nor is it the dry season or the rainy season. The word "return" when referring to the flood season is like a longing the locals have for a friend from afar.

Over the weekend, I heard my mother's voice on the phone, practically shouting with joy, saying that the floodwaters had come earlier and were higher than last year. She then asked if I wanted more snakehead fish sauce, saying that last year's catch was ready to eat this year, although she still wondered, "I wonder if there will be enough fish to make sauce for you all, because last year there were very few!"

The flood season in my childhood memories suddenly came back.

Remember around the 7th lunar month, the villagers were already bustling to welcome the pouring rains. They fixed their nets, traps, boats… waiting for the fish to return with the tide, watching the water surface overflowing the fields every day to predict whether the water level would be high or low.

Everywhere you go, you hear stories about the flood season from long ago, and from last year—stories that are told every year, but each time they sound as joyful as the first time you heard them. When the water rises, people are excitedly hoping to catch a lot of fish, and hardly anyone seems worried about the high water or floods.

Associate Professor Dr. Le Anh Tuan, an expert on climate change in the Mekong Delta (MD), said that the phrase “flood season” of the people of the MD is a folk concept that has existed since the formation of this land.

In fact, the phenomenon of rising water here is scientifically called flood. In Cambodia, there is also a similar phenomenon with rising water in the Mekong Delta, but your country still calls it flood.

Floodwaters inundate the fields, and people push nets to catch fish and shrimp during the flood season in Soc Trang . Photo: Trung Hieu

And nowadays, weather forecasts and documents in Vietnam use the term "flood" or "flood season" instead of "high water season." However, "floods in the Mekong Delta are different from those in mountainous regions; for the North and Central regions, floods are considered natural disasters," Mr. Tuan said.

According to Mr. Tuan, compared to floods in the Central region, the water rose very quickly and flowed rapidly, the water flow was also very short, the water could not escape, forming a flash flood phenomenon. People did not have time to respond, the flood destroyed crops and property wherever it came.

In the Mekong Delta, historically, the lower Mekong River has had three "water reservoirs": Tonle Sap Lake, the Dong Thap Muoi area, and the Long Xuyen Quadrangle.

Every year when upstream floods arrive, these three water reservoirs regulate the water supply for the area – during the flood season, they “store” the water, making the floods gentle, then gradually release it to replenish the Tien and Hau rivers, helping to push back saltwater intrusion. In this way, the water rises slowly, flows through the rivers, and overflows into the fields.

"Wherever the water rises, the people live with the natural flow of the floodwaters. Therefore, although it causes damage, it is not as much as the benefits it brings, so the people here look forward to it," the expert further explained.

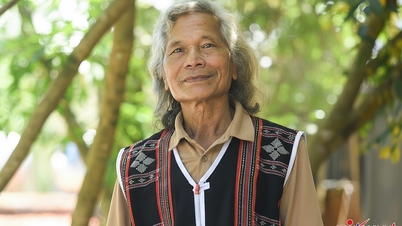

Professor Chung Hoang Chuong, a researcher on the Mekong River, said that the flood season is not only a natural phenomenon but also an indispensable part of the lives of people in the South.

Farmers here do both farming and gardening, and fish. With their high adaptability to the weather, they often see the flood season as an opportunity to change their way of making a living.

When the water returns, the fields are filled with alluvium and bring new life to the water lilies, reed grass, water chives, and the yellow flowers of the sesbania trees along the rivers and canals. This is also the season when flocks of birds return to nest, breed, and thrive in the fields, bamboo groves, and in the cajuput and mangrove forests.

In areas like Soc Trang, Hau Giang, Bac Lieu, the tide often comes late and income from aquatic resources is not as high as in the Long Xuyen Quadrangle and Dong Thap Muoi.

Back then, we mischievous children played according to the seasons. We were fascinated by the flooded fields, where the banks were invisible, making them look like vast oceans—something that children in the lowlands longed to see.

The sea was not blue but had the black color of alluvium and mother earth. We made our own fishing rods and used old nets, then we dived into the fields, swung the water, swung the gun to catch fish. For dinner that evening, the children were also provided with typical fish of the lower region such as perch, goby, and occasionally a few greedy snakehead fish.

In recent years, people have been less busy because the water level at the headwaters is low, the water for irrigation is scarce and comes in late, and aquatic resources have significantly decreased.

Many families no longer make a living from the flood season, except for those who live mainly from farming. Local authorities in many places have also come up with many models to help people adapt to the new situation, when the flood season is "not rising and erratic".

Having lived in Ward 2, Nga Nam town, Soc Trang province for nearly 55 years, Mr. Duong Van Lam said: “In the old days, during the flood season, out of ten households here, all ten made a living by fishing with hooks, nets, traps, and push nets. For the past five years or so, at most one or two households still do it, but they only catch a few fish to fill their meals; nobody makes a living from this anymore.”

In My Tu district and Nga Nam town, Soc Trang province, many livelihood models during the flood season have been implemented and brought benefits to many households, such as the fish farming model, the fish-rice farming model, and planting sedge instead of rice…

Mr. Lam is one of the farmers who has adapted to the changes of the flood season with the rice-fish model. Using 4,000 square meters of rice production, he started releasing fish from the 5th lunar month, with a rearing period of about six months to harvest.

The rice-fish farming model primarily utilizes food directly from the rice fields, while also improving soil quality. It is estimated that after deducting expenses, the family will earn tens of millions of dong more from this year's farming season.

This year, the Southern region is bustling, the rain is relatively more abundant than previous years, the water level is high(*). My mother said it must be because of the Year of the Dragon.

Although happy because the fields are irrigated, helping to remove acidity, wash away alum, kill pathogens, and deposit alluvium, Mom is still worried because the amount of fish and shrimp is still not much. However, to Mom, “looking out at the fields this season is so much fun!”

It seems that the presence of floodwaters, ultimately, can be a "cultural space" that shapes the people and the land.

Perhaps my mother, like many people in my hometown, didn't fully understand climate change, unaware of the serious consequences of unusually heavy rains. She was simply happy to see the water rising higher, because she believed that years with large floods meant a bountiful winter-spring crop the following year.

Source: https://danviet.vn/nuoc-tran-dong-vung-dau-nguon-mien-tay-dan-soc-trang-day-con-bat-ca-loc-dong-mam-loc-dong-ngon-20241112100811795.htm

![[Photo] Closing Ceremony of the 10th Session of the 15th National Assembly](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F11%2F1765448959967_image-1437-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh holds a phone call with the CEO of Russia's Rosatom Corporation.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F11%2F1765464552365_dsc-5295-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[OFFICIAL] MISA GROUP ANNOUNCES ITS PIONEERING BRAND POSITIONING IN BUILDING AGENTIC AI FOR BUSINESSES, HOUSEHOLDS, AND THE GOVERNMENT](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/12/11/1765444754256_agentic-ai_postfb-scaled.png)

Comment (0)