On the Dragon Boat Festival, the Nguyen dynasty emperors established specific regulations regarding rituals, offerings, banquets, holidays, firing of ceremonial cannons, flag hoisting, etc., both inside and outside the capital. These regulations varied throughout the reigns of the Nguyen emperors.

Records of the Dragon Boat Festival are extensively documented in historical texts, particularly in two valuable works compiled by the National History Institute of the Nguyen Dynasty: the Khâm Định Đại Nam Hội Điển Sự Lệ and the Đại Nam Thực Lục. Information from these two sources provides a comprehensive overview of the Dragon Boat Festival in Vietnam during the Nguyen Dynasty. This article will contribute further information on the festival, drawing from these two sources.

Regulations regarding holidays

In the 11th year of Minh Mệnh (1830), it was stipulated that one day before the Dragon Boat Festival, the construction and carpentry work in the capital would be suspended for two days (the 4th and 5th), and the offices of the Interior, Interior Affairs, and the Arsenal would be suspended for one day (the 5th).

By the 27th year of Tu Duc (1874), on the Dragon Boat Festival, there was only one day off, while the festivals of Saint's Birthday and the Longevity Festival were both two days off...

Regulations regarding etiquette

In the 3rd year of Gia Long (1804), regulations were established for rituals at temples and ancestral halls. At the Thai Mieu temple, the annual expenses for the New Year's Day, Dragon Boat Festival, offering sacrifices, memorial services, and other ceremonies amounted to 4,600 quan; the Trieu To temple spent over 370 quan annually.

By the 4th year of Gia Long (1805), regulations were established for ceremonies in the cities and towns. At the old temple in Gia Dinh, the two ceremonies of the Lunar New Year and the Dragon Boat Festival each received over 48 quan in funding. In Gia Dinh and Bac Thanh, the annual military parade each received 100 quan; at the Royal Palace, the three ceremonies of the Lunar New Year, the Longevity Festival, and the Dragon Boat Festival each received over 125 quan, while the towns and cities each received over 71 quan.

In the 12th year of Minh Mệnh (1831), it was stipulated that in localities outside the capital, on the occasion of the three major festivals of Vạn thọ, Nguyên đán, and Đoan dương, congratulatory letters and commemorative documents should only record the official title, and the use of official seals and stamps should be abandoned.

In the 16th year of Minh Mệnh (1835), regulations were added regarding annual festivals. There were five annual sacrificial ceremonies at the ancestral temple, and offerings were made during festivals such as Nguyên Đán, Thanh Minh, Đoan Dương, and Trừ Tịch to show reverence. It is now stipulated that feasts and offerings are made at the temples and shrines of Phụng Tiên during the Winter Solstice, Thượng Nguyên, Trung Nguyên, and Hạ Nguyên, with rituals similar to those of the Đoan Dương festival.

In the 13th year of Tu Duc (1860), during the Duan Yang festival, regulations were established to change the ceremonial procedures of the regular court. Previously, the Dong Yang festival was a grand celebratory court, and the Dong Chi festival was a regular court. Now, the Duan Yang festival was changed to a regular court, and the Dong Chi festival to a grand lower court. At the same time, it was stipulated that on the morning of the Duan Yang festival, the king would go to Gia Tho Palace to perform the ceremony. After the ceremony, the king would preside over the palace, hold the regular court ceremony, and suspend the officials inside and outside from submitting congratulatory petitions and holding a banquet."

Regulations regarding the offering of bird's nests and other offerings.

In the 5th year of Minh Mệnh (1824), on the Dragon Boat Festival. The day before, civil and military officials from the third rank upwards had a feast at the Cần Chánh Palace, while local commissioners and officials from the fourth rank downwards had a feast at the Imperial Court on the right.

In the 11th year of Minh Mệnh (1830), on the Dragon Boat Festival, if there was an imperial decree to give a feast and rewards, an additional thanksgiving ceremony would be held, and the "Di Bình" musical piece would be played without firing guns.

The regulations for banquets were changed in the 16th year of Minh Mệnh (1835). The old rule stated that: On the Dragon Boat Festival, during the plowing ceremony, and during the banquet, civil officials from the Lang Trung and military officials from the Phó Vệ Úy and above were allowed to attend. Cabinet members were also allowed to attend in a series. Now it has been changed: all ceremonies are to follow the previous regulations, and attendance is based on rank. However, Cabinet members, members of the Privy Council, and officials of the Ministry, Department, and Censorate are not allowed to attend any ceremony for which their rank is not yet sufficient.

In the 20th year of Minh Mệnh (1830), on the Dragon Boat Festival, the officials of the Imperial Academy and the Imperial Library were all allowed to attend the feast. This regulation was established as a rule to be followed later.

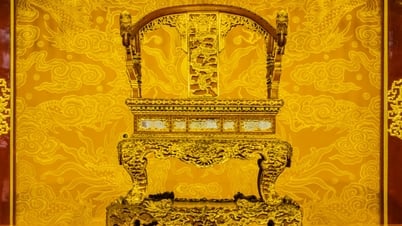

In the third year of the reign of Emperor Thieu Tri (1843), on the occasion of the Dragon Boat Festival, after the ceremony, the king went to the Thai Hoa Palace to receive congratulations; he hosted a banquet for the princes, royal relatives, and civil and military officials at the Can Chanh Palace, and rewarded them with fans, handkerchiefs, and tea and fruit.

In the 5th year of the reign of Emperor Thieu Tri (1845), on the Dragon Boat Festival, a banquet was held for the court officials. According to previous custom, the relevant departments compiled a list, and court officials, due to their low rank, were not allowed to attend. Now, the Emperor allowed court officials who were relatives of the foreign kingdom to attend to show his benevolence.

In the 6th year of Thieu Tri (1846), on the Dragon Boat Festival, besides princes, grandsons, and royal relatives, civil officials from the fifth rank and military officials from the fourth rank upwards, the sons of noble families who had been granted the title of Dinh Hau, along with civil officials from the fifth rank and military officials from the fourth rank, as well as officials selected to attend the court and those who submitted tributes or participated in training in the capital, were all allowed to attend and were granted a banquet.

In the 10th year of Tu Duc (1857), on the Dragon Boat Festival, a banquet was held for civil and military officials (civil officials from the fifth rank upwards, military officials from the fourth rank upwards) and they were rewarded with fans, handkerchiefs, tea, and fruit, according to their different ranks. This regulation became a custom to be followed from then on.

Regulations regarding firing signal cannons and raising flags.

In the 17th year of Gia Long (1818), it was established that ceremonial cannons be fired during self-celebration ceremonies and court ceremonies. For the three major festivals of Chính đán, Đoan dương, and Vạn thọ, nine cannon shots were fired when the king ascended the throne and entered the palace. In the 6th year of Minh Mệnh (1825), it was established that ceremonial cannons were fired when the king entered and exited the palace. For the major festivals of Vạn thọ, Nguyên đán, Đoan dương, Ban sóc, and the day of the great amnesty when the king ascended the throne to receive celebratory gifts, nine cannon shots were fired at the palace gate....

Regarding the custom of flying flags, in the 4th year of Minh Mạng (1823), it was stipulated that the Điện Hải watchtower and Định Hải fortress in Quảng Nam , being located on the sea, needed to be strictly observed. Three yellow flags were given to the officers at Điện Hải and Định Hải. On the occasions of Thánh thọ, Vạn thọ, Nguyên đán, Đoan dương… the custom of flying flags was followed.

Regarding the regulations for hanging flags at the flagpoles, in the 7th year of Minh Mệnh (1826), annually in the capital, on the four major festivals of Thánh thọ, Vạn thọ, Nguyên đán, and Đoan dương, and on the first and fifteenth days of the lunar month, when the royal procession entered and exited, large flags made of yellow sheepskin were hung; on ordinary days, small flags made of yellow cloth were hung. If there was heavy rain and wind, or on a day of mourning, the flags were not hung. In the cities, towns, districts, and the Trấn Hải, Điện Hải, and Định Hải flagpoles, on the four major festivals and when the royal procession arrived, large flags made of yellow sheepskin were hung; on the first and fifteenth days of the lunar month, and on ordinary days, small flags made of yellow cloth were hung. The flags varied in length and width. In the areas outside the capital, the large flags were replaced every three years, the small flags were replaced annually on the first and fifteenth days of the lunar month, and the small flags were replaced monthly on ordinary days.

Regarding the custom of hanging lanterns, it was previously done according to established rules, but in the 15th year of Minh Mệnh (1834), the custom of hanging lanterns on the occasions of Vạn Thọ, Nguyên Đán, Đoan Dương... in front of the palace courtyard and in front of Ngọ Môn was abolished.

In particular, in the first year of the reign of Emperor Thieu Tri (1841), on the Dragon Boat Festival, the officials submitted a petition regarding the celebration, but the Emperor, being in mourning, issued an edict prohibiting elaborate ceremonies. He also decreed that this year, on the Dragon Boat Festival and the day before the Emperor's birthday, yellow flags should be flown on the flagpoles in the capital, and high and low-ranking officials should attend. Outside, from local officials to civil and military staff working in the court, all should wear ceremonial robes. The offering of congratulatory petitions, the firing of celebratory cannons, and the attendance of local officials outside were abolished.

Regulations concerning the offering of silver and other gifts.

In the 7th year of Gia Long (1808), every year, during the ceremonies of longevity, New Year's Day, Dragon Boat Festival, etc., the regulations for offering silver were as follows: for the highest rank, each person received 5 taels; for the first rank, 4 taels; for the second rank, 3 taels and 5 coins; for the second rank, 3 taels; for the second rank, 2 taels and 5 coins; for the third rank, 2 taels; for the third rank, 1 tael and 5 coins; for the fourth rank, 1 tael; for the fourth rank, 9 coins and 5 fen....

By the third year of Minh Mệnh's reign (1822), the custom of offering silver changed during the Dragon Boat Festival. In the capital, it was divided according to rank: 100 taels for the Empress Dowager, 100 taels for the King, 100 taels for the Queen, and 90 taels for the Prince. Outside the capital, people were allowed to offer local products, submit petitions, and send representatives, while being exempt from offering silver... In the tenth year of Minh Mệnh's reign (1829), this custom was abolished.

Regarding offerings, in the 6th year of Minh Mệnh (1825), regulations were established for offering incense during sacrificial ceremonies. For the five ceremonies at Thái Miếu (Royal Palace Temple), the offerings for Chính Đán (the main festival) and Đoan Dương (the Dragon Boat Festival) consisted of 1 catty of agarwood, 8 taels of quick incense, and 1 catty 8 taels of sandalwood. For the five ceremonies at Thế Miếu (the main festival) and Đoan Dương, the offerings for Chính Đán and Đoan Dương consisted of 4 taels each of agarwood and quick incense, and 8 taels of sandalwood. For the five ceremonies at Triệu Miếu and Hưng Miếu (the main festival) and Đoan Dương, the offerings for Chính Đán and Đoan Dương consisted of 1 tael each of agarwood and quick incense, and 2 taels of sandalwood. For the two memorial ceremonies at Hoàng Nhân Palace, the offerings for Chính Đán and Đoan Dương consisted of 4 taels each of agarwood and quick incense, and 8 taels of sandalwood. All were cut into pieces, mixed thoroughly, and placed in bronze incense burners and bronze animal figures for burning.

In the 15th year of Minh Mệnh (1834), during the Dragon Boat Festival, according to tradition, every year during this festival, the provinces of Quảng Nam, Bình Định, and Phú Yên would harvest mangoes and transport them to the capital by land. However, due to the long and arduous journey, the king decided that during the offering period, Quảng Nam province, being closer to the capital, would continue the old custom, while Bình Định and Phú Yên would be allowed to transport them by water to reduce the burden on the people.

In the first year of the reign of Emperor Thieu Tri (1841), it was stipulated that, during annual sacrificial ceremonies, if there were early-ripening lemons available, Quang Nam province would purchase them. For the Dragon Boat Festival, the Longevity Festival, and the anniversary of the death of the Hieu Tu Temple, the Phu Yen province would follow the same procedure, with 600 lemons each, to be brought to the capital on the appointed day.

In the first year of Thanh Thai (1889), during the festivals of Doan Duong, Tam Nguyen (Thuong Nguyen, Trung Nguyen, Ha Nguyen), Trung Duong, That Tich, and Dong Chi, offerings were made in full of gold and silver, incense, candles, sandalwood tea, betel nuts, wine, and fruits.

Dress code

In the 11th year of Minh Mệnh (1830), it was stipulated that the wives of civil and military officials from the third rank upwards would make their own court attire according to their rank, and on the three major festivals of Thánh thọ, Nguyên đán, and Đoan dương at Từ Thọ Palace, they would all follow the prescribed rituals in the inner court.

In the 18th year of Minh Mệnh (1837), when the king went out for pleasure, on the anniversary of the death of a deceased person at the temples, during the festivals of Chính đán and Đoan dương... the Imperial Guards and Royal Guards escorting the king were forbidden from wearing red or purple.

In the second year of the reign of Emperor Thieu Tri (1842), on the Dragon Boat Festival, the king and his officials went to Tu Tho Palace to celebrate the festival. After the ceremony, the king returned to Van Minh Palace, and the princes, royal relatives, civil officials from the fifth rank and military officials from the fourth rank and above all dressed in fine clothes and came to the palace courtyard to pay their respects. Due to the national mourning period, the day before and on the day of the festival, the officials in the palace wore blue and black robes and headscarves to attend to the king.

In the 28th year of Tu Duc (1875), regulations were established regarding the attire for the Dragon Boat Festival celebration. On this day, the regular court was held at Can Chanh Palace. Civil officials of the fifth rank, military officials of the fourth rank, and those with titles of the third rank and above, all wore robes with embroidered cloth and waited in the Tho Chi Gate. The king, dressed in fine robes, passed through the Imperial Palace to Gia Tho Palace, summoning the royal relatives, princes, civil and military officials, seal holders, and those with titles of the third rank and above, as well as the royal son-in-law, to enter. Civil officials of the fifth rank, military officials of the fourth rank, and those with titles of the fourth rank all stood in attendance in front of the Tho Chi Gate. The king went first to perform the ceremonial bow, and after the king finished, all the officials bowed.

It can be seen that, during the Dragon Boat Festival (Doan Ngo), the Nguyen dynasty emperors had specific regulations regarding rituals, organization methods, offerings, rewards, etc. These regulations were recorded as precedents and practiced both inside and outside the capital. These regulations/precedents contributed to enriching the cultural and spiritual life of the Vietnamese people.

Source

![[Image] First Congress of the Vietnam Science and Technology Trade Union](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F24%2F1766552551054_ndo_tr_img-1801-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[VIMC 40 Days of Rapid Progress] VOSCO Container Transportation Department | Perseverance – Connection – Innovation – Breakthrough](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/12/24/1766545965846_vimc-40day-vosco-24-12-25.jpeg)

Comment (0)