For the ethnic minorities of the Central Highlands in general, and the Ba Na people in particular, the communal house is considered the "heart" of the entire village. With its important position in both material and spiritual life, the communal house is always cherished by the people, regarded as the very soul of their ethnic group.

A place that preserves the soul and essence of the Ba Na ethnic group.

Amidst the vast, sun-drenched, and windswept forest, the communal house stands majestically in the center of the village, like a guardian deity protecting the entire community.

This is where villagers gather for communal activities, where people chat, share life experiences, organize festivals, or perform traditional rituals.

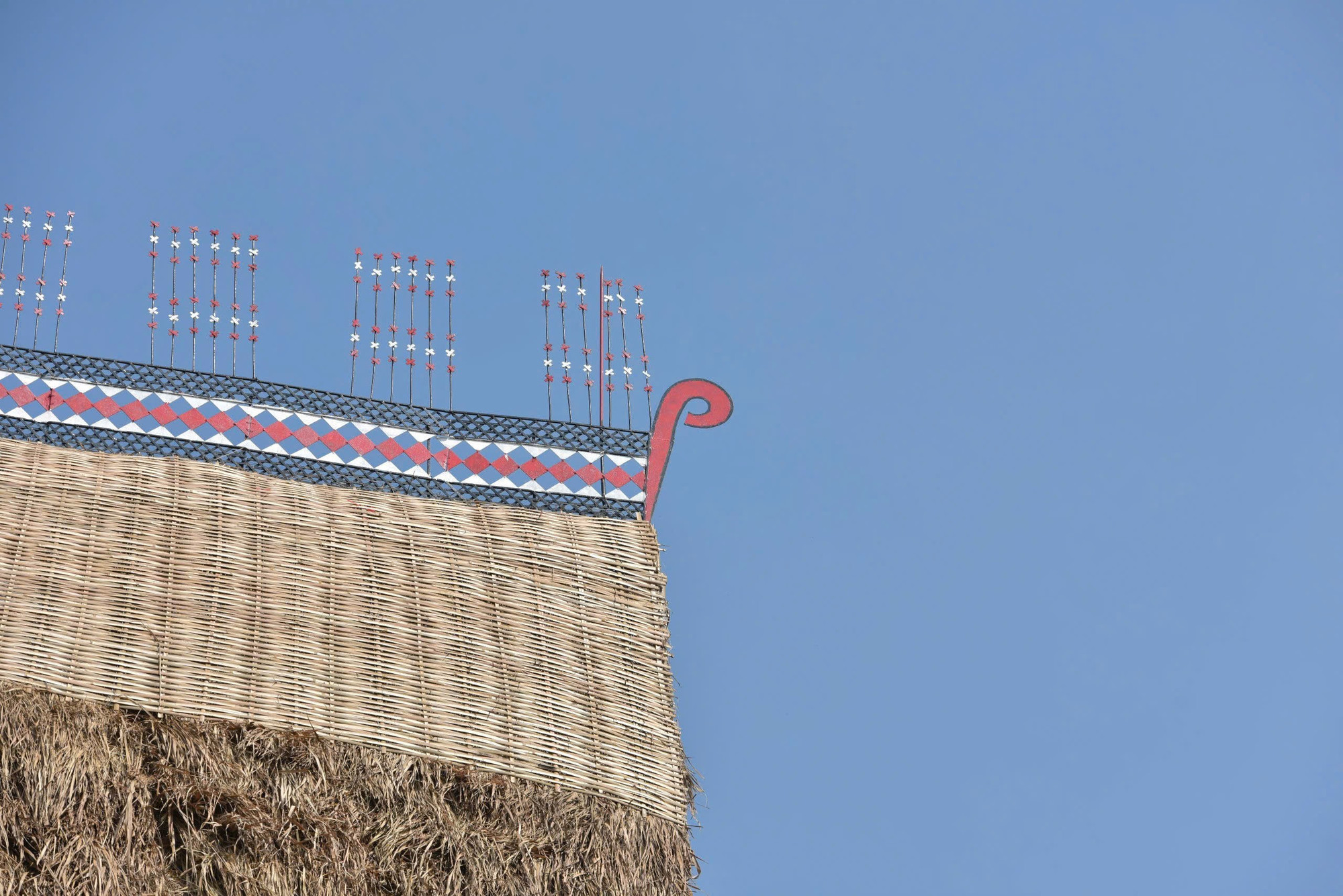

The communal houses of the Ba Na people are typically tall, massive, and imposing, yet graceful. The roofs are commonly 15 to 20 meters high, shaped like the letter A, with the apex decorated with a unique pattern. The four roofs are thatched with grass. The two main roofs are very large, covered with woven mats that extend down to varying degrees depending on the village, sometimes almost completely covering the roof, making it look more beautiful and also protecting it from strong winds. The two gable roofs are isosceles triangles.

The floor of a communal house (nhà rông) is usually between 2 and 3 meters high. Inside, the house is constructed from eight large wooden pillars, with a common three-bay design; it is often elaborately decorated with intricate patterns and sculptures. The entrance opens in the center of the front of the house, across the courtyard, and then to the staircase.

The communal house was built by the villagers entirely from materials they gathered from the forest, such as wood, bamboo, reeds, vines, and thatch grass; no metal materials were used at all.

For a long time, many villages in the Central Highlands lacked communal houses for various reasons: traditional houses were damaged and not restored, people built new houses using modern materials, etc.

In recent years, the movement to restore the communal house (nhà rông) has received significant attention, with organization and investment from the State and implementation by the local people. These traditional communal houses have become tourist attractions, drawing many visitors to learn about and explore the culture and people of the Ba Na ethnic group.

Seeing the house is seeing the village.

To contribute to honoring the national culture and spreading the image of the Ba Na communal house, the Vietnam Museum of Ethnology (Hanoi) is preserving a prototype of a traditional Ba Na communal house, built more than 20 years ago by Ba Na artisans in Kon Rbang village, Ngok Bay commune, Quang Ngai province (formerly Kon Tum ).

According to Dr. Bui Ngoc Quang, Deputy Director in charge of the museum, during the development process, many traditional communal houses have gradually been replaced by communal houses with corrugated iron roofs, reinforced concrete communal houses, or other modern materials. The museum has chosen a typical communal house model of the Ba Na people in Ngok Bay commune to reconstruct, thereby helping the public and tourists to better understand the architecture and cultural value of the traditional house.

Recently, the museum organized a restoration project for the house with the participation of 20 Ba Na people who worked for over a month.

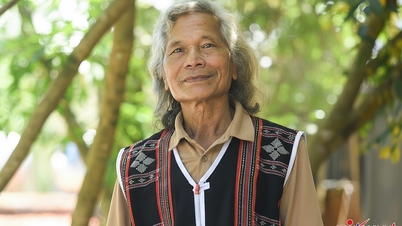

Inside the traditional Ba Na communal house at the Vietnam Museum of Ethnology, village elder A Ngêh (born in 1953) from Kon Rbàng village, Ngọk Bay commune, enthusiastically shared his joy that the house, built according to the traditional model, has become more spacious and beautiful. He was delighted that there is also a Ba Na communal house in the capital city. Tourists from all over the country and even foreigners can learn more about Ba Na culture.

“The first time we went to the museum to rebuild the communal house was in 2003, when the group had 30 people, and now half of them are gone. Old people like us are in poor health and have difficulty getting around, but we still want to bring the younger generation to Hanoi to rebuild the communal house. Seeing the communal house means seeing the village of the Ba Na people. Seeing the house restored with my own eyes, I feel at peace,” village elder A Ngêh confided.

Artisan A Wang (born in 1964) continued the story: “Nowadays in the village, when repairing the communal house, many young people participate. They know how to split thatch, erect pillars, and build roofs… The elders guide them, and the young people can do everything. I only hope that the young people will continue building communal houses and preserve the identity of the Ba Na people. If we don't do it, we will forget it.”

Persistently preserving the 'soul' of the village.

According to Dr. Bui Ngoc Quang, for sustainable preservation, the Vietnam Museum of Ethnology adheres to four basic principles: Respecting and promoting the role of cultural subjects; each exhibition has a clear identity, owner, history, and location; the items are created by local people using traditional methods; and finally, presenting a comprehensive overview of both the material and spiritual life associated with the building.

This approach enables museums not only to "preserve artifacts" but also to conserve living heritage, recreating the relationship between humans, nature, and culture.

However, restoring the communal house is not easy. Dr. Bui Ngoc Quang believes that nowadays there are not many opportunities for the younger generation to learn how to build traditional communal houses, partly because of the scarcity of materials, and partly because of the impact of modern life, which has led to a decrease in the number of communal houses. Therefore, each time a communal house is built or renovated, it is an opportunity for the elders to guide the younger generation on how to construct and build a traditional communal house.

“The construction, repair, and restoration of the communal house is not simply a matter of construction techniques, but also carries many rituals and customs with unique spiritual significance that need to be preserved and protected. Each restoration of the communal house is also an opportunity for the culture of the Tây Nguyên highlands to be continued and passed on to future generations,” Mr. Quang said.

Dr. Bui Ngoc Quang emphasized that the communal house is the soul of the village, a place that nurtures the memories and spiritual strength of the people of the Central Highlands. Therefore, preserving the communal house is not just about retaining an architectural structure, but about preserving the way of life, the way of thinking, and the way of behaving of the community.

Dr. Luu Hung, former Deputy Director of the Vietnam Museum of Ethnology, shares this view. He believes that the restoration of the communal house is a persistent process that demonstrates the deep connection between people and heritage.

In 2003, when the museum invited artisans from Kon Rbang village to Hanoi to reconstruct the communal house at the museum, the communal house in Kon Rbang village was no longer in its traditional form, but had been rebuilt with a corrugated iron roof.

However, after the communal house at the museum was restored, the artisans returned to the village and encouraged the villagers to re-roof the communal house in Kon Rbàng village with thatch, following the traditional model of the Ba Na people of the Central Highlands.

According to Dr. Luu Hung, the construction and restoration of communal houses require specific techniques and materials: The pillars must be made from green starwood with a diameter of 45-60cm to ensure durability for hundreds of years, and the top of the pillars needs to be made from old-growth forest wood so that it can be bent to the traditional shape.

During the restoration process, it is estimated that the Ba Na people contributed more than 3,350 man-days of labor from January 2002 until the inauguration in June 2003, including both renovations.

“Every bamboo panel, every pillar carries the effort and affection of the Ba Na people. After many years, their return to personally repair their own houses is proof of the enduring value of their living culture,” said Mr. Luu Hung.

After more than two decades of exposure to the elements and urban environment, the Ba Na communal house at the museum still retains its sturdy and majestic appearance, symbolizing the strength, unity, and spiritual life of the Central Highlands people.

Source: https://www.vietnamplus.vn/bao-ton-nha-rong-cua-nguoi-ba-na-giu-hon-dan-toc-giua-long-pho-thi-post1072004.vnp

![[Photo] Closing Ceremony of the 10th Session of the 15th National Assembly](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F11%2F1765448959967_image-1437-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[OFFICIAL] MISA GROUP ANNOUNCES ITS PIONEERING BRAND POSITIONING IN BUILDING AGENTIC AI FOR BUSINESSES, HOUSEHOLDS, AND THE GOVERNMENT](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/12/11/1765444754256_agentic-ai_postfb-scaled.png)

Comment (0)