EDITOR'S NOTE

EDITOR'S NOTE To commemorate the 69th anniversary of Vietnamese Doctors' Day (February 27th), VietNamNet presents to readers a series of articles titled "Genetics: Following in the Footsteps and Shining Brightly." This is the story of families with multiple generations, whose members have all donned the white coat. In this context, parents have become great teachers, pioneers, and trailblazers, while their children not only choose to follow in their footsteps but also shoulder the responsibility of continuing to develop and shine.  Professor Dr. Nguyen Tai Son, former Head of the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery and Plastic Surgery at Military Central Hospital 108, has only one daughter, Dr. Nguyen Hong Nhung, 40 years old, who works at Hospital E and is also a lecturer in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vietnam National University, Hanoi. Maxillofacial surgery and microplastic surgery are rarely pursued by female doctors in Vietnam due to the demanding and arduous nature of the field. However, Professor Son's journey to having Dr. Hong Nhung excel in this area has been filled with many surprises and heartaches. “Initially, Nhung didn’t want to go to medical school, but I advised her to pursue this very humane profession,” the professor, who is about to turn 70, began his story with VietNamNet. Dr. Nhung studied medicine in Russia, and during summer breaks, she would return to Military Hospital 108 to intern as a medical staff member in various roles. First, she worked as a nurse, visiting patients, taking their temperature and blood pressure. The following year, she returned as a nurse, then as a doctor's assistant, examining and monitoring patients. She progressed through these ranks.

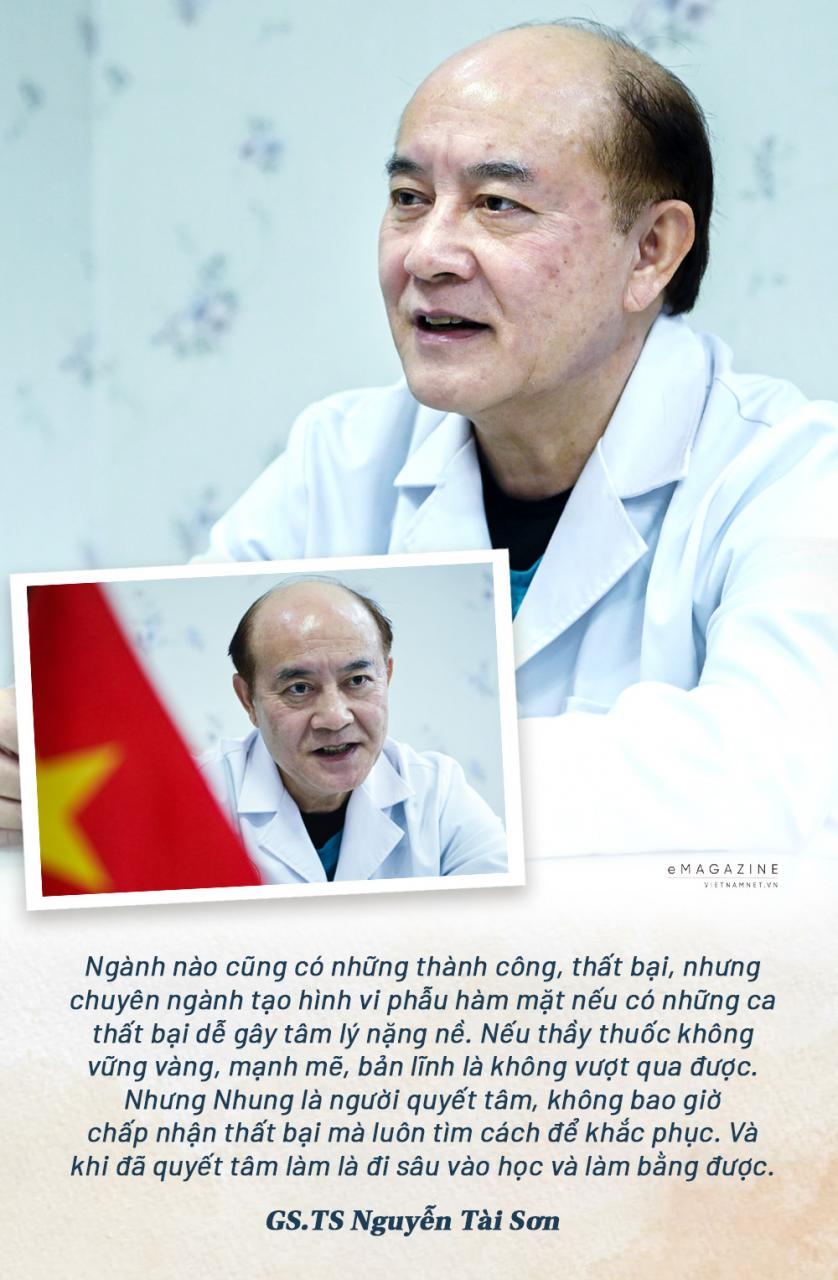

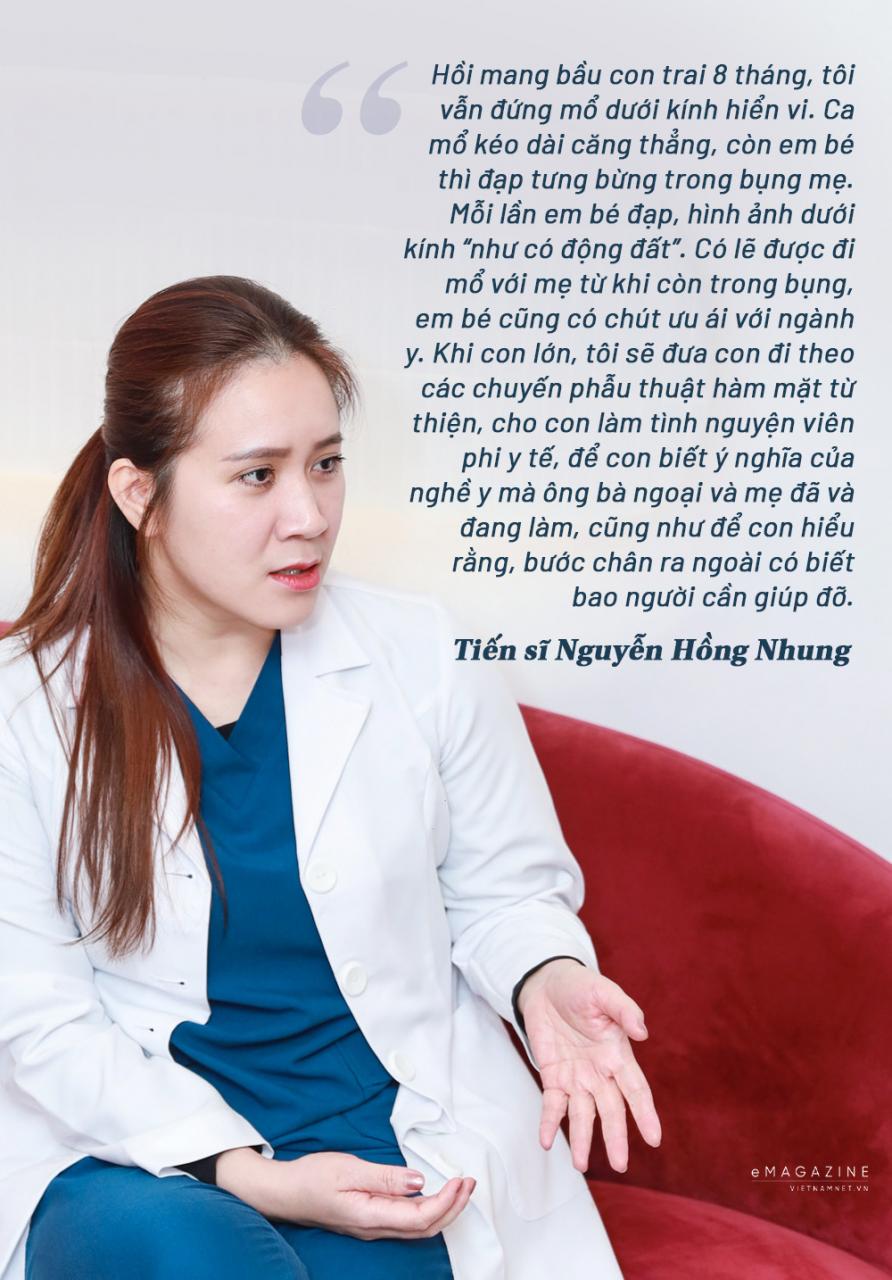

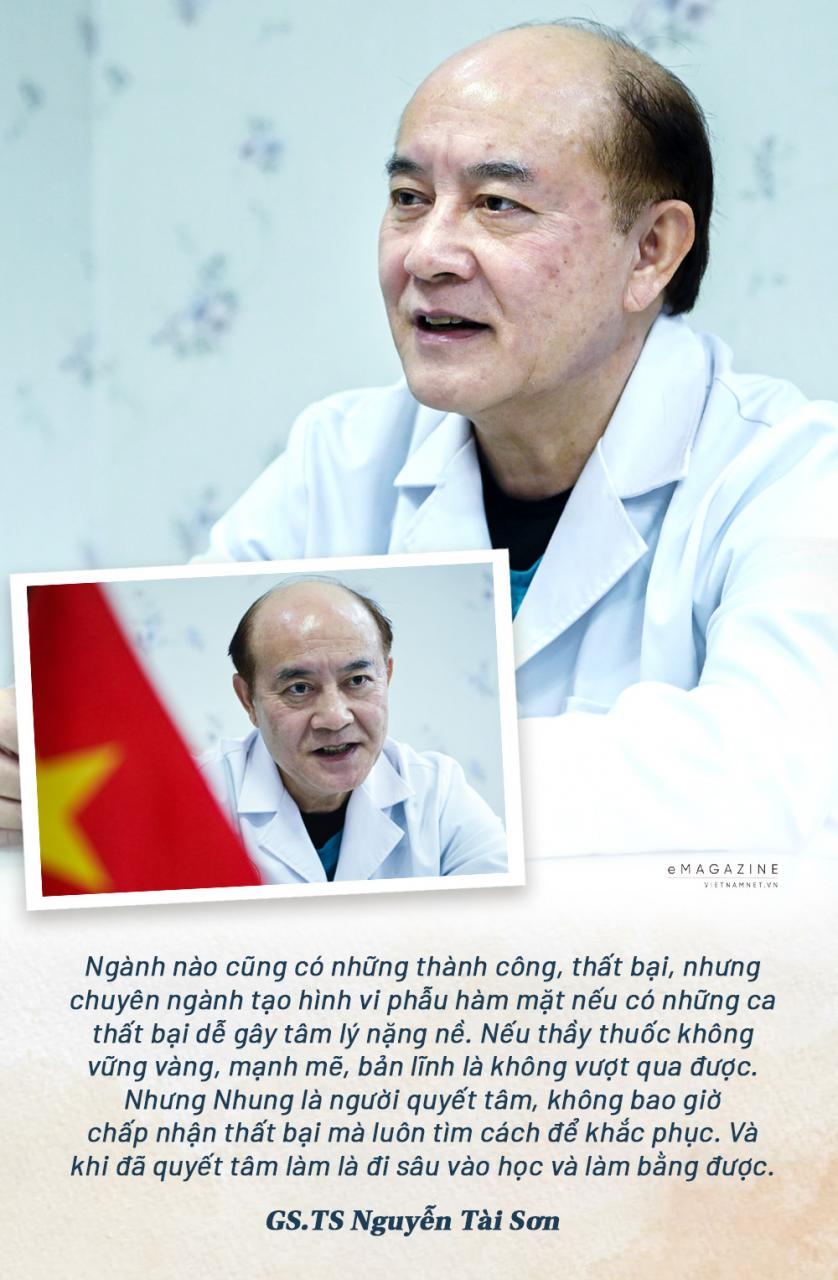

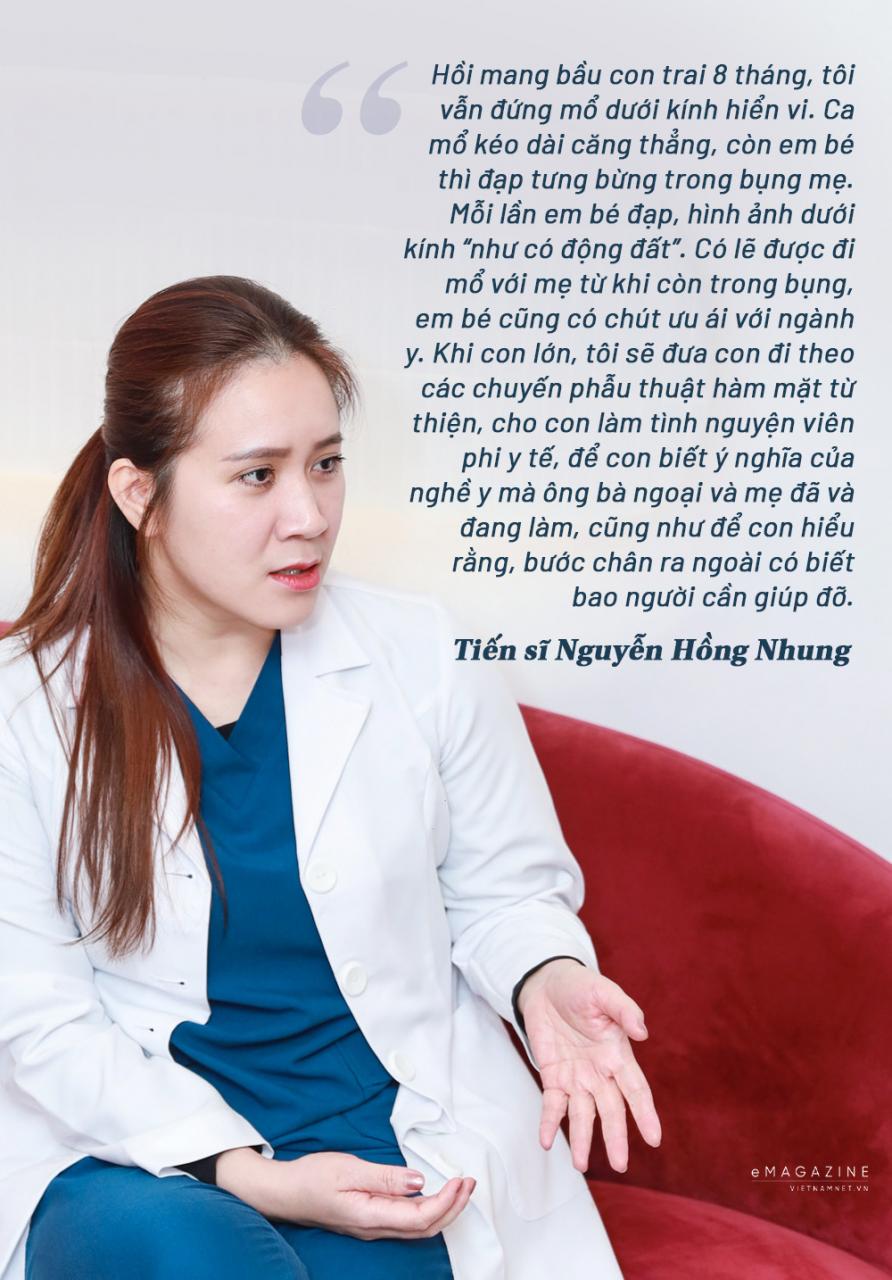

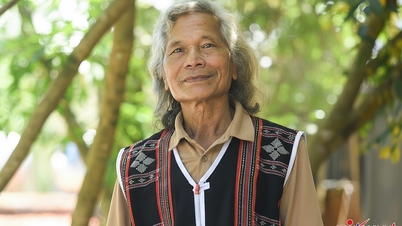

Professor Dr. Nguyen Tai Son, former Head of the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery and Plastic Surgery at Military Central Hospital 108, has only one daughter, Dr. Nguyen Hong Nhung, 40 years old, who works at Hospital E and is also a lecturer in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vietnam National University, Hanoi. Maxillofacial surgery and microplastic surgery are rarely pursued by female doctors in Vietnam due to the demanding and arduous nature of the field. However, Professor Son's journey to having Dr. Hong Nhung excel in this area has been filled with many surprises and heartaches. “Initially, Nhung didn’t want to go to medical school, but I advised her to pursue this very humane profession,” the professor, who is about to turn 70, began his story with VietNamNet. Dr. Nhung studied medicine in Russia, and during summer breaks, she would return to Military Hospital 108 to intern as a medical staff member in various roles. First, she worked as a nurse, visiting patients, taking their temperature and blood pressure. The following year, she returned as a nurse, then as a doctor's assistant, examining and monitoring patients. She progressed through these ranks.  At that time, Dr. Nguyen Tai Son was considered by his colleagues at the hospital to be one of the most skilled microsurgeons, not only within the hospital but also nationwide. He encouraged his children to pursue medicine, but at the time, he never hoped they would follow his specialty, because "it's wonderful, but it's very hard work." "Each microsurgery operation lasts a very long time, usually 7-8 hours, not including complex cases which can last even longer. It can last day and night, up to 22-24 hours continuously, with only a 30-minute break before continuing," Professor Son recalled. Furthermore, post-operative monitoring is crucial, even determining the success of the entire microsurgery team. This monitoring involves not only the patient's vital signs but also the vital signs of the injured area (due to tumor removal, scarring, or deformities from trauma) and the free flap (a healthy area taken to compensate for the defect). If the free flap after surgery doesn't heal properly and becomes necrotic, the surgery is a complete failure. The patient will suffer double damage. Therefore, in 2010, when his 26-year-old daughter graduated from medical school, her father advised her to become an ophthalmologist because the work was less strenuous and more suitable for women. But Dr. Nhung, since childhood, has been a determined and adventurous person. "After accompanying my father to the microsurgery operating room to observe him and his colleagues performing major surgeries, and probably seeing for the first time in her life a reconstructive surgery that seemed new and complex, and witnessing surgical results that changed people's lives, Nhung decided to pursue this specialty," he recounted. In fact, Dr. Nhung only worked in ophthalmology for a mere 30 days before resolutely choosing microsurgery. “When I insisted on pursuing this demanding and arduous specialty, my father strongly objected, saying, ‘Why would a girl choose this? Why not choose a lighter job more suitable for a girl?’ My father said this field demands physical strength, operating from morning till night, skipping meals is common, especially for those who have to lead major surgeries. Not to mention, women also have to take care of children and families. After surgery, the work isn't over; you still have to constantly monitor the patient even after they've gone home, and then at night, if anything unusual happens, the doctor has to rush back to the patient,” Dr. Nhung continued. But all the opposition from her parents (who are also doctors) couldn't overcome the heartfelt devotion of their only daughter. Now, more than 12 years later, Dr. Nhung fully understands and appreciates her father's words. “This job can save lives and restore a good life to many people who have fallen into ‘the abyss,’ and that’s what motivates me to stay committed to the field of microsurgery and maxillofacial surgery, which is often considered unsuitable for women,” she said. “There are cases where, after a surgery during the day, I get a call from Nhung’s department in the middle of the night, and I have to rush in. I only have time to tell the family that I need to take the patient to the hospital for emergency treatment, and sometimes I stay there until morning,” Dr. Son recounted. But she shared: If given the choice again, she would still choose this job.

At that time, Dr. Nguyen Tai Son was considered by his colleagues at the hospital to be one of the most skilled microsurgeons, not only within the hospital but also nationwide. He encouraged his children to pursue medicine, but at the time, he never hoped they would follow his specialty, because "it's wonderful, but it's very hard work." "Each microsurgery operation lasts a very long time, usually 7-8 hours, not including complex cases which can last even longer. It can last day and night, up to 22-24 hours continuously, with only a 30-minute break before continuing," Professor Son recalled. Furthermore, post-operative monitoring is crucial, even determining the success of the entire microsurgery team. This monitoring involves not only the patient's vital signs but also the vital signs of the injured area (due to tumor removal, scarring, or deformities from trauma) and the free flap (a healthy area taken to compensate for the defect). If the free flap after surgery doesn't heal properly and becomes necrotic, the surgery is a complete failure. The patient will suffer double damage. Therefore, in 2010, when his 26-year-old daughter graduated from medical school, her father advised her to become an ophthalmologist because the work was less strenuous and more suitable for women. But Dr. Nhung, since childhood, has been a determined and adventurous person. "After accompanying my father to the microsurgery operating room to observe him and his colleagues performing major surgeries, and probably seeing for the first time in her life a reconstructive surgery that seemed new and complex, and witnessing surgical results that changed people's lives, Nhung decided to pursue this specialty," he recounted. In fact, Dr. Nhung only worked in ophthalmology for a mere 30 days before resolutely choosing microsurgery. “When I insisted on pursuing this demanding and arduous specialty, my father strongly objected, saying, ‘Why would a girl choose this? Why not choose a lighter job more suitable for a girl?’ My father said this field demands physical strength, operating from morning till night, skipping meals is common, especially for those who have to lead major surgeries. Not to mention, women also have to take care of children and families. After surgery, the work isn't over; you still have to constantly monitor the patient even after they've gone home, and then at night, if anything unusual happens, the doctor has to rush back to the patient,” Dr. Nhung continued. But all the opposition from her parents (who are also doctors) couldn't overcome the heartfelt devotion of their only daughter. Now, more than 12 years later, Dr. Nhung fully understands and appreciates her father's words. “This job can save lives and restore a good life to many people who have fallen into ‘the abyss,’ and that’s what motivates me to stay committed to the field of microsurgery and maxillofacial surgery, which is often considered unsuitable for women,” she said. “There are cases where, after a surgery during the day, I get a call from Nhung’s department in the middle of the night, and I have to rush in. I only have time to tell the family that I need to take the patient to the hospital for emergency treatment, and sometimes I stay there until morning,” Dr. Son recounted. But she shared: If given the choice again, she would still choose this job.  In 2011, at the age of 27, Dr. Nhung began studying maxillofacial surgery and microplastic surgery. At that time, her father, Professor Son, was already a master in this field with 26 years of experience. But even this leading expert admitted: "My daughter has grown up surprisingly fast." The doctor still clearly remembers the days his daughter and her friends practiced connecting blood vessels all afternoon. Connecting blood vessels on a rat's abdomen was very difficult because the blood vessels were tiny, less than 1mm in diameter, only the size of a round toothpick. While the outer layer was thin, transparent when a drop of water was placed on it, it couldn't swell without water, and the two walls would collapse and stick together, making it impossible to thread a suture through. Because it was so difficult, many trainees gave up. Yet, young Dr. Nguyen Hong Nhung was one of the trainees who successfully conquered it. Professor Son also clearly remembers the moment he realized his daughter, whom he thought was a pampered young lady, could pursue this surgical profession. According to Dr. Son, who has nearly 30 years of experience in the profession, the most fundamental aspect of being a "microsurgeon" is practicing under a microscope and whether their hands tremble. "If a surgeon trembles, they'll be shaking even when holding surgical instruments normally, but under a microscope with a magnification of 20 times, trembling hands would be like stirring porridge or mixing blood pudding," he said, using a metaphor. When he noticed his daughter's steady hands and calm, unwavering expression, he believed he had found his "successor."

In 2011, at the age of 27, Dr. Nhung began studying maxillofacial surgery and microplastic surgery. At that time, her father, Professor Son, was already a master in this field with 26 years of experience. But even this leading expert admitted: "My daughter has grown up surprisingly fast." The doctor still clearly remembers the days his daughter and her friends practiced connecting blood vessels all afternoon. Connecting blood vessels on a rat's abdomen was very difficult because the blood vessels were tiny, less than 1mm in diameter, only the size of a round toothpick. While the outer layer was thin, transparent when a drop of water was placed on it, it couldn't swell without water, and the two walls would collapse and stick together, making it impossible to thread a suture through. Because it was so difficult, many trainees gave up. Yet, young Dr. Nguyen Hong Nhung was one of the trainees who successfully conquered it. Professor Son also clearly remembers the moment he realized his daughter, whom he thought was a pampered young lady, could pursue this surgical profession. According to Dr. Son, who has nearly 30 years of experience in the profession, the most fundamental aspect of being a "microsurgeon" is practicing under a microscope and whether their hands tremble. "If a surgeon trembles, they'll be shaking even when holding surgical instruments normally, but under a microscope with a magnification of 20 times, trembling hands would be like stirring porridge or mixing blood pudding," he said, using a metaphor. When he noticed his daughter's steady hands and calm, unwavering expression, he believed he had found his "successor."  After receiving guidance from her father and practicing under his supervision, and independently mastering the suturing technique, the young female doctor progressed to the stages of free flap harvesting, dissection, vascular access, and suturing. Her maturity surprised her "father-mentor," Nguyen Tai Son. Although they worked at different hospitals, because they were in the same field, Dr. Nhung and her colleagues still invited Professor Nguyen Tai Son to the hospital for consultations and demonstration surgeries to learn from. "After a while, when they were confident, my father would supervise them closely to ensure they felt secure performing the surgeries. If they encountered any difficulties or problems, they could ask questions right there on the 'scene.' After a few such instances, I was always by her side, like a driving instructor. When I saw she was confident, I felt reassured and let her drive herself," he recalled. Even in the early years of her independence, Professor Son maintained the habit of monitoring his daughter's progress, knowing her daily and weekly surgery schedule. “Whenever my daughter had surgery, I would keep track of the closing time. If it was getting late and I hadn’t received a message from her, I would call to ask. Usually, she would hand the phone to the technician, always asking how the surgery went, if there were any difficulties, or if she needed my help,” he said. Perhaps it was this close and thorough supervision from her father that allowed Dr. Nhung to become so "strong" so quickly, even beyond the expectations of Professor Son and his colleagues. As colleagues in the same field, bringing patient cases home for discussion between Dr. Son and his daughter was very normal. Both interesting cases and those that weren't so good were "analyzed." “My daughter isn’t afraid to ask questions and argue,” the professor humorously recounted about his strong-willed daughter, whom he dotes on but is also very strict with.

After receiving guidance from her father and practicing under his supervision, and independently mastering the suturing technique, the young female doctor progressed to the stages of free flap harvesting, dissection, vascular access, and suturing. Her maturity surprised her "father-mentor," Nguyen Tai Son. Although they worked at different hospitals, because they were in the same field, Dr. Nhung and her colleagues still invited Professor Nguyen Tai Son to the hospital for consultations and demonstration surgeries to learn from. "After a while, when they were confident, my father would supervise them closely to ensure they felt secure performing the surgeries. If they encountered any difficulties or problems, they could ask questions right there on the 'scene.' After a few such instances, I was always by her side, like a driving instructor. When I saw she was confident, I felt reassured and let her drive herself," he recalled. Even in the early years of her independence, Professor Son maintained the habit of monitoring his daughter's progress, knowing her daily and weekly surgery schedule. “Whenever my daughter had surgery, I would keep track of the closing time. If it was getting late and I hadn’t received a message from her, I would call to ask. Usually, she would hand the phone to the technician, always asking how the surgery went, if there were any difficulties, or if she needed my help,” he said. Perhaps it was this close and thorough supervision from her father that allowed Dr. Nhung to become so "strong" so quickly, even beyond the expectations of Professor Son and his colleagues. As colleagues in the same field, bringing patient cases home for discussion between Dr. Son and his daughter was very normal. Both interesting cases and those that weren't so good were "analyzed." “My daughter isn’t afraid to ask questions and argue,” the professor humorously recounted about his strong-willed daughter, whom he dotes on but is also very strict with.  Professor Son and his daughter have maintained a habit for over 10 years: taking photos and sending them immediately after each surgery. "I have a habit of taking photos of the harvested free flap and the treated area after the operation. My father is the first to receive those images," Dr. Nhung shared. Many times, after waiting for her daughter's photos to finish, the professor would proactively text her to urge her to hurry. Upon receiving her message and seeing the good results, he would calmly reply briefly: "That's good!", or more generously, he would praise her: "Neat and clean," Dr. Nhung happily boasted.

Professor Son and his daughter have maintained a habit for over 10 years: taking photos and sending them immediately after each surgery. "I have a habit of taking photos of the harvested free flap and the treated area after the operation. My father is the first to receive those images," Dr. Nhung shared. Many times, after waiting for her daughter's photos to finish, the professor would proactively text her to urge her to hurry. Upon receiving her message and seeing the good results, he would calmly reply briefly: "That's good!", or more generously, he would praise her: "Neat and clean," Dr. Nhung happily boasted.  At nearly 70 years old, with approximately 40 years of experience as a mentor to many generations of surgical and reconstructive specialists nationwide, and now retired, Professor Son still maintains the habit of observing his younger colleagues performing microsurgery like his daughter. He is strict and sparing with praise for his daughter, but when he sees an image of a colleague successfully performing a flap surgery, he immediately sends a message of encouragement, even if he doesn't know who they are or where they work. He is secretly proud of the development of this specialty, even though in reality very few young doctors are eager to pursue it. “International experts assess the skills and techniques of Vietnamese doctors in microsurgery as being on par with others, comparable to major centers in Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea… At prestigious international scientific conferences attended by thousands of experts in this field, the reports and images submitted by Vietnamese doctors are even considered more impressive,” the professor proudly shared. According to him, this development is due to the younger generation's ability to absorb advanced global techniques, apply technology and techniques effectively, and work in teams very efficiently. "This is completely different from before, when we were primarily responsible for individual tasks," he said. Sharing more about the applications of digital technology and techniques in maxillofacial surgery and microsurgical reconstruction, Dr. Nhung proudly mentioned the virtual surgery model that her team pioneered. According to the doctor, using digital technology to reconstruct defects and injuries provides high accuracy in achieving aesthetic results. For example, in cases where a patient needs jawbone removal, the 2D X-rays of the past cannot provide the same level of support as 3D reconstructions today. The team also established a virtual surgical team before officially performing the actual surgery. This team includes data collectors, patient image captureers, 3D modelers, and then develops surgical methods based on digitized tumor resection designs, measurements, and calculations of defect areas. “Previously, defect reconstruction relied on the technician's experience. For example, to remove a defect on one side of the jawbone, the doctor had to measure the joint separately and create a symmetrical shape. The accuracy was only relative. With the support of digital technology, after the resection, the software can create a perfect facial reconstruction, from which the distance and defect can be calculated to print accurate images for the actual bone resection surgery,” Dr. Nhung explained. Acknowledging the superiority of this next generation, Dr. Son affirmed: “Even if patients lose half or almost all of their jawbone, their face remains virtually unchanged after surgery. Furthermore, the bite is well preserved, making post-operative dental restoration very convenient. Patients wear dentures, and the surgical scars are less noticeable, making it difficult to detect that they have undergone major surgery.”

At nearly 70 years old, with approximately 40 years of experience as a mentor to many generations of surgical and reconstructive specialists nationwide, and now retired, Professor Son still maintains the habit of observing his younger colleagues performing microsurgery like his daughter. He is strict and sparing with praise for his daughter, but when he sees an image of a colleague successfully performing a flap surgery, he immediately sends a message of encouragement, even if he doesn't know who they are or where they work. He is secretly proud of the development of this specialty, even though in reality very few young doctors are eager to pursue it. “International experts assess the skills and techniques of Vietnamese doctors in microsurgery as being on par with others, comparable to major centers in Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea… At prestigious international scientific conferences attended by thousands of experts in this field, the reports and images submitted by Vietnamese doctors are even considered more impressive,” the professor proudly shared. According to him, this development is due to the younger generation's ability to absorb advanced global techniques, apply technology and techniques effectively, and work in teams very efficiently. "This is completely different from before, when we were primarily responsible for individual tasks," he said. Sharing more about the applications of digital technology and techniques in maxillofacial surgery and microsurgical reconstruction, Dr. Nhung proudly mentioned the virtual surgery model that her team pioneered. According to the doctor, using digital technology to reconstruct defects and injuries provides high accuracy in achieving aesthetic results. For example, in cases where a patient needs jawbone removal, the 2D X-rays of the past cannot provide the same level of support as 3D reconstructions today. The team also established a virtual surgical team before officially performing the actual surgery. This team includes data collectors, patient image captureers, 3D modelers, and then develops surgical methods based on digitized tumor resection designs, measurements, and calculations of defect areas. “Previously, defect reconstruction relied on the technician's experience. For example, to remove a defect on one side of the jawbone, the doctor had to measure the joint separately and create a symmetrical shape. The accuracy was only relative. With the support of digital technology, after the resection, the software can create a perfect facial reconstruction, from which the distance and defect can be calculated to print accurate images for the actual bone resection surgery,” Dr. Nhung explained. Acknowledging the superiority of this next generation, Dr. Son affirmed: “Even if patients lose half or almost all of their jawbone, their face remains virtually unchanged after surgery. Furthermore, the bite is well preserved, making post-operative dental restoration very convenient. Patients wear dentures, and the surgical scars are less noticeable, making it difficult to detect that they have undergone major surgery.”

Professor Dr. Nguyen Tai Son, former Head of the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery and Plastic Surgery at Military Central Hospital 108, has only one daughter, Dr. Nguyen Hong Nhung, 40 years old, who works at Hospital E and is also a lecturer in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vietnam National University, Hanoi. Maxillofacial surgery and microplastic surgery are rarely pursued by female doctors in Vietnam due to the demanding and arduous nature of the field. However, Professor Son's journey to having Dr. Hong Nhung excel in this area has been filled with many surprises and heartaches. “Initially, Nhung didn’t want to go to medical school, but I advised her to pursue this very humane profession,” the professor, who is about to turn 70, began his story with VietNamNet. Dr. Nhung studied medicine in Russia, and during summer breaks, she would return to Military Hospital 108 to intern as a medical staff member in various roles. First, she worked as a nurse, visiting patients, taking their temperature and blood pressure. The following year, she returned as a nurse, then as a doctor's assistant, examining and monitoring patients. She progressed through these ranks.

Professor Dr. Nguyen Tai Son, former Head of the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery and Plastic Surgery at Military Central Hospital 108, has only one daughter, Dr. Nguyen Hong Nhung, 40 years old, who works at Hospital E and is also a lecturer in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery at the University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vietnam National University, Hanoi. Maxillofacial surgery and microplastic surgery are rarely pursued by female doctors in Vietnam due to the demanding and arduous nature of the field. However, Professor Son's journey to having Dr. Hong Nhung excel in this area has been filled with many surprises and heartaches. “Initially, Nhung didn’t want to go to medical school, but I advised her to pursue this very humane profession,” the professor, who is about to turn 70, began his story with VietNamNet. Dr. Nhung studied medicine in Russia, and during summer breaks, she would return to Military Hospital 108 to intern as a medical staff member in various roles. First, she worked as a nurse, visiting patients, taking their temperature and blood pressure. The following year, she returned as a nurse, then as a doctor's assistant, examining and monitoring patients. She progressed through these ranks.  At that time, Dr. Nguyen Tai Son was considered by his colleagues at the hospital to be one of the most skilled microsurgeons, not only within the hospital but also nationwide. He encouraged his children to pursue medicine, but at the time, he never hoped they would follow his specialty, because "it's wonderful, but it's very hard work." "Each microsurgery operation lasts a very long time, usually 7-8 hours, not including complex cases which can last even longer. It can last day and night, up to 22-24 hours continuously, with only a 30-minute break before continuing," Professor Son recalled. Furthermore, post-operative monitoring is crucial, even determining the success of the entire microsurgery team. This monitoring involves not only the patient's vital signs but also the vital signs of the injured area (due to tumor removal, scarring, or deformities from trauma) and the free flap (a healthy area taken to compensate for the defect). If the free flap after surgery doesn't heal properly and becomes necrotic, the surgery is a complete failure. The patient will suffer double damage. Therefore, in 2010, when his 26-year-old daughter graduated from medical school, her father advised her to become an ophthalmologist because the work was less strenuous and more suitable for women. But Dr. Nhung, since childhood, has been a determined and adventurous person. "After accompanying my father to the microsurgery operating room to observe him and his colleagues performing major surgeries, and probably seeing for the first time in her life a reconstructive surgery that seemed new and complex, and witnessing surgical results that changed people's lives, Nhung decided to pursue this specialty," he recounted. In fact, Dr. Nhung only worked in ophthalmology for a mere 30 days before resolutely choosing microsurgery. “When I insisted on pursuing this demanding and arduous specialty, my father strongly objected, saying, ‘Why would a girl choose this? Why not choose a lighter job more suitable for a girl?’ My father said this field demands physical strength, operating from morning till night, skipping meals is common, especially for those who have to lead major surgeries. Not to mention, women also have to take care of children and families. After surgery, the work isn't over; you still have to constantly monitor the patient even after they've gone home, and then at night, if anything unusual happens, the doctor has to rush back to the patient,” Dr. Nhung continued. But all the opposition from her parents (who are also doctors) couldn't overcome the heartfelt devotion of their only daughter. Now, more than 12 years later, Dr. Nhung fully understands and appreciates her father's words. “This job can save lives and restore a good life to many people who have fallen into ‘the abyss,’ and that’s what motivates me to stay committed to the field of microsurgery and maxillofacial surgery, which is often considered unsuitable for women,” she said. “There are cases where, after a surgery during the day, I get a call from Nhung’s department in the middle of the night, and I have to rush in. I only have time to tell the family that I need to take the patient to the hospital for emergency treatment, and sometimes I stay there until morning,” Dr. Son recounted. But she shared: If given the choice again, she would still choose this job.

At that time, Dr. Nguyen Tai Son was considered by his colleagues at the hospital to be one of the most skilled microsurgeons, not only within the hospital but also nationwide. He encouraged his children to pursue medicine, but at the time, he never hoped they would follow his specialty, because "it's wonderful, but it's very hard work." "Each microsurgery operation lasts a very long time, usually 7-8 hours, not including complex cases which can last even longer. It can last day and night, up to 22-24 hours continuously, with only a 30-minute break before continuing," Professor Son recalled. Furthermore, post-operative monitoring is crucial, even determining the success of the entire microsurgery team. This monitoring involves not only the patient's vital signs but also the vital signs of the injured area (due to tumor removal, scarring, or deformities from trauma) and the free flap (a healthy area taken to compensate for the defect). If the free flap after surgery doesn't heal properly and becomes necrotic, the surgery is a complete failure. The patient will suffer double damage. Therefore, in 2010, when his 26-year-old daughter graduated from medical school, her father advised her to become an ophthalmologist because the work was less strenuous and more suitable for women. But Dr. Nhung, since childhood, has been a determined and adventurous person. "After accompanying my father to the microsurgery operating room to observe him and his colleagues performing major surgeries, and probably seeing for the first time in her life a reconstructive surgery that seemed new and complex, and witnessing surgical results that changed people's lives, Nhung decided to pursue this specialty," he recounted. In fact, Dr. Nhung only worked in ophthalmology for a mere 30 days before resolutely choosing microsurgery. “When I insisted on pursuing this demanding and arduous specialty, my father strongly objected, saying, ‘Why would a girl choose this? Why not choose a lighter job more suitable for a girl?’ My father said this field demands physical strength, operating from morning till night, skipping meals is common, especially for those who have to lead major surgeries. Not to mention, women also have to take care of children and families. After surgery, the work isn't over; you still have to constantly monitor the patient even after they've gone home, and then at night, if anything unusual happens, the doctor has to rush back to the patient,” Dr. Nhung continued. But all the opposition from her parents (who are also doctors) couldn't overcome the heartfelt devotion of their only daughter. Now, more than 12 years later, Dr. Nhung fully understands and appreciates her father's words. “This job can save lives and restore a good life to many people who have fallen into ‘the abyss,’ and that’s what motivates me to stay committed to the field of microsurgery and maxillofacial surgery, which is often considered unsuitable for women,” she said. “There are cases where, after a surgery during the day, I get a call from Nhung’s department in the middle of the night, and I have to rush in. I only have time to tell the family that I need to take the patient to the hospital for emergency treatment, and sometimes I stay there until morning,” Dr. Son recounted. But she shared: If given the choice again, she would still choose this job.  In 2011, at the age of 27, Dr. Nhung began studying maxillofacial surgery and microplastic surgery. At that time, her father, Professor Son, was already a master in this field with 26 years of experience. But even this leading expert admitted: "My daughter has grown up surprisingly fast." The doctor still clearly remembers the days his daughter and her friends practiced connecting blood vessels all afternoon. Connecting blood vessels on a rat's abdomen was very difficult because the blood vessels were tiny, less than 1mm in diameter, only the size of a round toothpick. While the outer layer was thin, transparent when a drop of water was placed on it, it couldn't swell without water, and the two walls would collapse and stick together, making it impossible to thread a suture through. Because it was so difficult, many trainees gave up. Yet, young Dr. Nguyen Hong Nhung was one of the trainees who successfully conquered it. Professor Son also clearly remembers the moment he realized his daughter, whom he thought was a pampered young lady, could pursue this surgical profession. According to Dr. Son, who has nearly 30 years of experience in the profession, the most fundamental aspect of being a "microsurgeon" is practicing under a microscope and whether their hands tremble. "If a surgeon trembles, they'll be shaking even when holding surgical instruments normally, but under a microscope with a magnification of 20 times, trembling hands would be like stirring porridge or mixing blood pudding," he said, using a metaphor. When he noticed his daughter's steady hands and calm, unwavering expression, he believed he had found his "successor."

In 2011, at the age of 27, Dr. Nhung began studying maxillofacial surgery and microplastic surgery. At that time, her father, Professor Son, was already a master in this field with 26 years of experience. But even this leading expert admitted: "My daughter has grown up surprisingly fast." The doctor still clearly remembers the days his daughter and her friends practiced connecting blood vessels all afternoon. Connecting blood vessels on a rat's abdomen was very difficult because the blood vessels were tiny, less than 1mm in diameter, only the size of a round toothpick. While the outer layer was thin, transparent when a drop of water was placed on it, it couldn't swell without water, and the two walls would collapse and stick together, making it impossible to thread a suture through. Because it was so difficult, many trainees gave up. Yet, young Dr. Nguyen Hong Nhung was one of the trainees who successfully conquered it. Professor Son also clearly remembers the moment he realized his daughter, whom he thought was a pampered young lady, could pursue this surgical profession. According to Dr. Son, who has nearly 30 years of experience in the profession, the most fundamental aspect of being a "microsurgeon" is practicing under a microscope and whether their hands tremble. "If a surgeon trembles, they'll be shaking even when holding surgical instruments normally, but under a microscope with a magnification of 20 times, trembling hands would be like stirring porridge or mixing blood pudding," he said, using a metaphor. When he noticed his daughter's steady hands and calm, unwavering expression, he believed he had found his "successor."  After receiving guidance from her father and practicing under his supervision, and independently mastering the suturing technique, the young female doctor progressed to the stages of free flap harvesting, dissection, vascular access, and suturing. Her maturity surprised her "father-mentor," Nguyen Tai Son. Although they worked at different hospitals, because they were in the same field, Dr. Nhung and her colleagues still invited Professor Nguyen Tai Son to the hospital for consultations and demonstration surgeries to learn from. "After a while, when they were confident, my father would supervise them closely to ensure they felt secure performing the surgeries. If they encountered any difficulties or problems, they could ask questions right there on the 'scene.' After a few such instances, I was always by her side, like a driving instructor. When I saw she was confident, I felt reassured and let her drive herself," he recalled. Even in the early years of her independence, Professor Son maintained the habit of monitoring his daughter's progress, knowing her daily and weekly surgery schedule. “Whenever my daughter had surgery, I would keep track of the closing time. If it was getting late and I hadn’t received a message from her, I would call to ask. Usually, she would hand the phone to the technician, always asking how the surgery went, if there were any difficulties, or if she needed my help,” he said. Perhaps it was this close and thorough supervision from her father that allowed Dr. Nhung to become so "strong" so quickly, even beyond the expectations of Professor Son and his colleagues. As colleagues in the same field, bringing patient cases home for discussion between Dr. Son and his daughter was very normal. Both interesting cases and those that weren't so good were "analyzed." “My daughter isn’t afraid to ask questions and argue,” the professor humorously recounted about his strong-willed daughter, whom he dotes on but is also very strict with.

After receiving guidance from her father and practicing under his supervision, and independently mastering the suturing technique, the young female doctor progressed to the stages of free flap harvesting, dissection, vascular access, and suturing. Her maturity surprised her "father-mentor," Nguyen Tai Son. Although they worked at different hospitals, because they were in the same field, Dr. Nhung and her colleagues still invited Professor Nguyen Tai Son to the hospital for consultations and demonstration surgeries to learn from. "After a while, when they were confident, my father would supervise them closely to ensure they felt secure performing the surgeries. If they encountered any difficulties or problems, they could ask questions right there on the 'scene.' After a few such instances, I was always by her side, like a driving instructor. When I saw she was confident, I felt reassured and let her drive herself," he recalled. Even in the early years of her independence, Professor Son maintained the habit of monitoring his daughter's progress, knowing her daily and weekly surgery schedule. “Whenever my daughter had surgery, I would keep track of the closing time. If it was getting late and I hadn’t received a message from her, I would call to ask. Usually, she would hand the phone to the technician, always asking how the surgery went, if there were any difficulties, or if she needed my help,” he said. Perhaps it was this close and thorough supervision from her father that allowed Dr. Nhung to become so "strong" so quickly, even beyond the expectations of Professor Son and his colleagues. As colleagues in the same field, bringing patient cases home for discussion between Dr. Son and his daughter was very normal. Both interesting cases and those that weren't so good were "analyzed." “My daughter isn’t afraid to ask questions and argue,” the professor humorously recounted about his strong-willed daughter, whom he dotes on but is also very strict with.  Professor Son and his daughter have maintained a habit for over 10 years: taking photos and sending them immediately after each surgery. "I have a habit of taking photos of the harvested free flap and the treated area after the operation. My father is the first to receive those images," Dr. Nhung shared. Many times, after waiting for her daughter's photos to finish, the professor would proactively text her to urge her to hurry. Upon receiving her message and seeing the good results, he would calmly reply briefly: "That's good!", or more generously, he would praise her: "Neat and clean," Dr. Nhung happily boasted.

Professor Son and his daughter have maintained a habit for over 10 years: taking photos and sending them immediately after each surgery. "I have a habit of taking photos of the harvested free flap and the treated area after the operation. My father is the first to receive those images," Dr. Nhung shared. Many times, after waiting for her daughter's photos to finish, the professor would proactively text her to urge her to hurry. Upon receiving her message and seeing the good results, he would calmly reply briefly: "That's good!", or more generously, he would praise her: "Neat and clean," Dr. Nhung happily boasted.  At nearly 70 years old, with approximately 40 years of experience as a mentor to many generations of surgical and reconstructive specialists nationwide, and now retired, Professor Son still maintains the habit of observing his younger colleagues performing microsurgery like his daughter. He is strict and sparing with praise for his daughter, but when he sees an image of a colleague successfully performing a flap surgery, he immediately sends a message of encouragement, even if he doesn't know who they are or where they work. He is secretly proud of the development of this specialty, even though in reality very few young doctors are eager to pursue it. “International experts assess the skills and techniques of Vietnamese doctors in microsurgery as being on par with others, comparable to major centers in Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea… At prestigious international scientific conferences attended by thousands of experts in this field, the reports and images submitted by Vietnamese doctors are even considered more impressive,” the professor proudly shared. According to him, this development is due to the younger generation's ability to absorb advanced global techniques, apply technology and techniques effectively, and work in teams very efficiently. "This is completely different from before, when we were primarily responsible for individual tasks," he said. Sharing more about the applications of digital technology and techniques in maxillofacial surgery and microsurgical reconstruction, Dr. Nhung proudly mentioned the virtual surgery model that her team pioneered. According to the doctor, using digital technology to reconstruct defects and injuries provides high accuracy in achieving aesthetic results. For example, in cases where a patient needs jawbone removal, the 2D X-rays of the past cannot provide the same level of support as 3D reconstructions today. The team also established a virtual surgical team before officially performing the actual surgery. This team includes data collectors, patient image captureers, 3D modelers, and then develops surgical methods based on digitized tumor resection designs, measurements, and calculations of defect areas. “Previously, defect reconstruction relied on the technician's experience. For example, to remove a defect on one side of the jawbone, the doctor had to measure the joint separately and create a symmetrical shape. The accuracy was only relative. With the support of digital technology, after the resection, the software can create a perfect facial reconstruction, from which the distance and defect can be calculated to print accurate images for the actual bone resection surgery,” Dr. Nhung explained. Acknowledging the superiority of this next generation, Dr. Son affirmed: “Even if patients lose half or almost all of their jawbone, their face remains virtually unchanged after surgery. Furthermore, the bite is well preserved, making post-operative dental restoration very convenient. Patients wear dentures, and the surgical scars are less noticeable, making it difficult to detect that they have undergone major surgery.”

At nearly 70 years old, with approximately 40 years of experience as a mentor to many generations of surgical and reconstructive specialists nationwide, and now retired, Professor Son still maintains the habit of observing his younger colleagues performing microsurgery like his daughter. He is strict and sparing with praise for his daughter, but when he sees an image of a colleague successfully performing a flap surgery, he immediately sends a message of encouragement, even if he doesn't know who they are or where they work. He is secretly proud of the development of this specialty, even though in reality very few young doctors are eager to pursue it. “International experts assess the skills and techniques of Vietnamese doctors in microsurgery as being on par with others, comparable to major centers in Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea… At prestigious international scientific conferences attended by thousands of experts in this field, the reports and images submitted by Vietnamese doctors are even considered more impressive,” the professor proudly shared. According to him, this development is due to the younger generation's ability to absorb advanced global techniques, apply technology and techniques effectively, and work in teams very efficiently. "This is completely different from before, when we were primarily responsible for individual tasks," he said. Sharing more about the applications of digital technology and techniques in maxillofacial surgery and microsurgical reconstruction, Dr. Nhung proudly mentioned the virtual surgery model that her team pioneered. According to the doctor, using digital technology to reconstruct defects and injuries provides high accuracy in achieving aesthetic results. For example, in cases where a patient needs jawbone removal, the 2D X-rays of the past cannot provide the same level of support as 3D reconstructions today. The team also established a virtual surgical team before officially performing the actual surgery. This team includes data collectors, patient image captureers, 3D modelers, and then develops surgical methods based on digitized tumor resection designs, measurements, and calculations of defect areas. “Previously, defect reconstruction relied on the technician's experience. For example, to remove a defect on one side of the jawbone, the doctor had to measure the joint separately and create a symmetrical shape. The accuracy was only relative. With the support of digital technology, after the resection, the software can create a perfect facial reconstruction, from which the distance and defect can be calculated to print accurate images for the actual bone resection surgery,” Dr. Nhung explained. Acknowledging the superiority of this next generation, Dr. Son affirmed: “Even if patients lose half or almost all of their jawbone, their face remains virtually unchanged after surgery. Furthermore, the bite is well preserved, making post-operative dental restoration very convenient. Patients wear dentures, and the surgical scars are less noticeable, making it difficult to detect that they have undergone major surgery.”Vo Thu - Vietnamnet.vn

Source

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh holds a phone call with the CEO of Russia's Rosatom Corporation.](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F11%2F1765464552365_dsc-5295-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] Closing Ceremony of the 10th Session of the 15th National Assembly](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F11%2F1765448959967_image-1437-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[OFFICIAL] MISA GROUP ANNOUNCES ITS PIONEERING BRAND POSITIONING IN BUILDING AGENTIC AI FOR BUSINESSES, HOUSEHOLDS, AND THE GOVERNMENT](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/12/11/1765444754256_agentic-ai_postfb-scaled.png)

Comment (0)