Without an intermediate layer to act as a “buffer” between the provincial vision and the implementation at the grassroots level, all planning decisions at the commune level become more direct and faster, but at the same time, they also pose more risks if there is a lack of coordination and capacity. Therefore, the question is no longer “should we decentralize or not?”, but rather how to redesign the coordination mechanism and capacity building program in a two-tier structure to make the system operate smoothly.

As a common property

First of all, we must look directly at the nature of planning. Planning is not just a set of drawings dividing residential land, production land or a map of routes. Planning is a strategic tool of the state at the provincial level to organize living space, production space, infrastructure space and ecological space in the medium and long term.

Every planning decision, even if it takes place at the commune level, still affects the inter-commune road system, the ability to escape floods, the technical and social infrastructure network, and the safety of people in the face of climate change. When the local government model is still two-level, every planning decision at the commune level must be placed within the overall framework outlined by the province; otherwise, the overall map will be divided into separate, difficult-to-connect pieces.

In this context, it is easy to fall into one of two polarities. One is “absolute centralization”, where the province tries to do everything from top to bottom, leaving the commune with only a passive implementation role. The other is to hand over the entire shaping of local space to the commune with the reason that “the commune is closest to the people and understands the people best”.

If the province does everything, planning can easily become disconnected from life, especially in rural and suburban areas where livelihood models and cultures are very diverse. Communes, when they do it themselves, without sufficient professional capacity and data infrastructure, can easily optimize locally, sacrificing the long-term benefits of the wider region. A smart two-tier model must reconcile both, by establishing a strong coordination mechanism at the provincial level and a new role for communes: not as “reluctant planning architects” but as “eyes, ears, and hands” of the planning system.

A close look reveals a huge gap between expectations and capacity at the commune level. At the commune level, there is usually only one cadastral - construction - environment department, where a few people are burdened with too many tasks, from land surveying, dispute resolution, construction order management to reporting environmental issues. In-depth capacity in urban planning, spatial planning, technical infrastructure, traffic analysis, and disaster risk assessment is often very limited. The ability to use digital tools such as GIS, mapping software, and access to planning databases is also uneven...

In addition, planning does not stop at the commune boundary. A commune that expands residential land to low-lying areas, fills natural lakes, and builds houses on drainage corridors will push the risk of flooding to neighboring communes. A commune that develops tourist areas and riverside motels may inadvertently block the rescue route for the entire riverside during heavy rains. If many communes optimize according to local goals such as increasing residential land area and attracting a few short-term projects, the entire provincial space will be bent according to those calculations. Without the district level to “filter” proposals, the role of coordination and “guarding the big picture” of the province becomes even more vital.

However, it would be a mistake to keep the commune out of the planning task because of those risks. The commune is the place closest to the people, and understands best the very specific needs that are difficult to see from the province: which road is often flooded, which residential area lacks public space, which stream is being suffocated by waste, which hillside is eroding, which people's livelihood is being narrowed because of unreasonable planning boundaries...

When the province designs a plan without listening to the commune, without collecting data and voices from the commune, it is easy to draw beautiful maps on paper but difficult to put into practice. The participation of the commune not only makes the plan "more real" but also creates a sense of co-ownership, helping people accept and protect the plan as a common asset.

The way to reconcile these two aspects is to clearly redefine the role and authority of the commune in the planning process. The commune is not the place to design the regional spatial structure, but the place to provide current data, propose needs and development scenarios at the micro level, organize community consultations, criticize the planning options proposed by the province, and finally, the place to implement and supervise the implementation. The province must take on all the coordination, analysis, integration and decision-making tasks. The commune "does not lose its rights" but on the contrary, its role of participation is formalized in an orderly and procedural manner, instead of both lacking/weak expertise and being expected to take on tasks beyond its scope.

Hierarchy comes with role assignment

To function well, the province must build a strong enough “planning brain”. This could be an agency equivalent to the provincial urban planning and redevelopment authority, responsible for three things: developing a long-term vision and spatial framework, operating a data system and analytical tools, and coordinating all interactions with the communes.

This brain must rely on a relatively complete digital data infrastructure: topographic maps, infrastructure networks, land use status, disaster risk areas, conservation areas, and projects that have been and are being implemented. All of this information needs to be organized in a shared map system, which each commune can access, read, and update part of the field data. This is the foundation for all planning ideas at the commune level to be placed on the same information plane with the vision of the province.

On the commune side, capacity building here has at least four groups: awareness, basic expertise, data skills and community working skills.

Commune leaders need to understand that planning is not just about adding residential land and projects, but also about protecting ecological space, protecting people's safety, and protecting the development potential of future generations.

Cadres in charge of land administration and construction need to be equipped with at least the ability to read and understand planning maps, and grasp the minimum principles of construction density, boundaries, traffic safety corridors, and water source protection corridors.

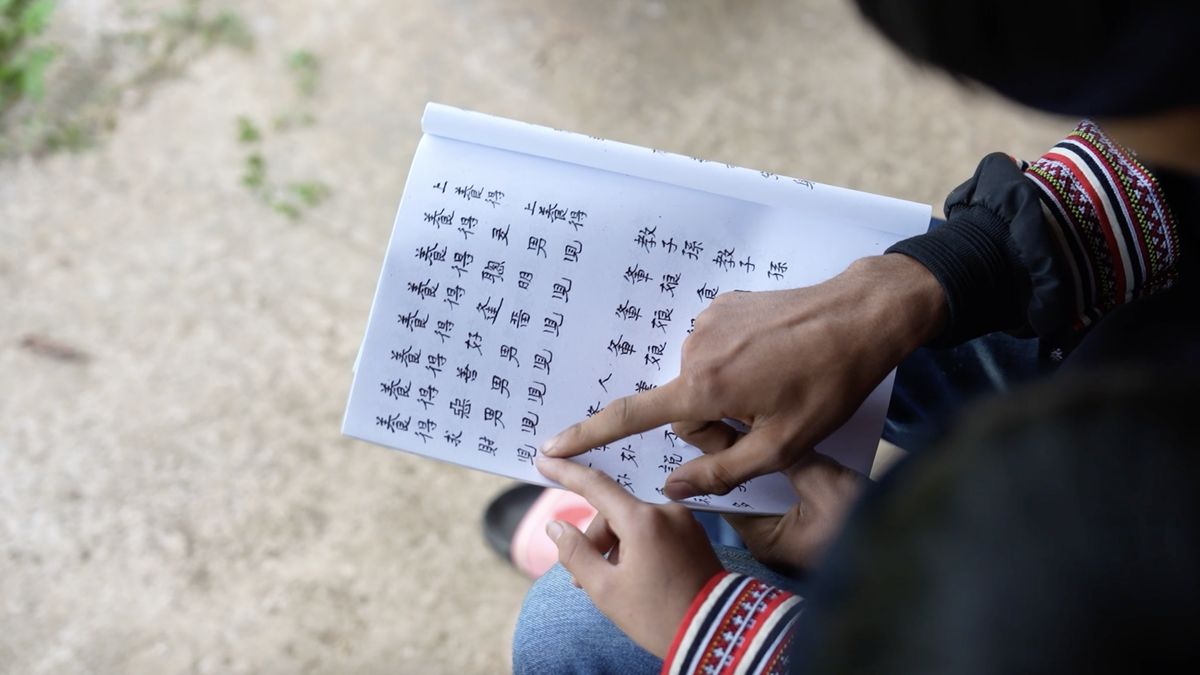

Communes need to learn how to use digital map viewing tools, record flooding, landslides, environmental, population, and infrastructure hotspots to send to the province in a structured manner.

Communes must know how to organize consultation sessions, explain planning in easy-to-understand language, and honestly record and synthesize people's opinions.

Once the commune has such basic capacity, the planning hierarchy process in the two-tier model can be designed to be both rigorous and flexible. The province periodically publishes and updates the master spatial planning framework; the commune uses this to review the current situation and propose micro-adjustments such as widening some residential roads, arranging small public spaces, reorganizing market spaces, wharves, and small-scale handicraft production areas. The province receives, analyzes, evaluates, and then decides to accept, adjust, or reject. In that process, the commune participates from beginning to end, but the final decision still belongs to the provincial level, which owns the whole picture.

All of this can only really work if there is a clear monitoring and accountability mechanism. Communes cannot use the excuse of “lack of capacity” to shirk responsibility when proposing solutions that only serve short-term or small-group interests. Provinces cannot use the excuse of “trusting the commune” to approve easily. Decentralization is the art of assigning roles so that the person closest to the people has more say, while the person with a vision for the whole region has greater responsibility.

If this can be done, the decentralization of planning to communes in the 2-tier local government model will become an opportunity to renew the thinking of spatial management. The province must upgrade its data platform, analysis tools and reorganize the planning apparatus in a more professional direction, instead of being scattered. Communes must become more mature in their perception of development to move towards a safe and trustworthy living space for the people. People, through participation mechanisms, will see more clearly the connection between their opinions and the lines on the planning map.

Source: https://baodanang.vn/phan-cap-lap-va-quan-ly-quy-hoach-3313820.html

![[Photo] 60th Anniversary of the Founding of the Vietnam Association of Photographic Artists](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F05%2F1764935864512_a1-bnd-0841-9740-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] National Assembly Chairman Tran Thanh Man attends the VinFuture 2025 Award Ceremony](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F05%2F1764951162416_2628509768338816493-6995-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)