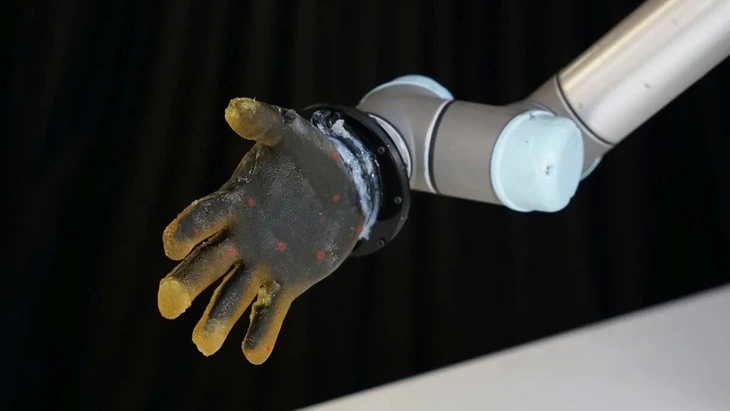

Close-up of the robotic hand with hydrogel skin - Photo: Cambridge University

No longer just a movie, robots today are gradually becoming capable of sensing touch, temperature, and even injury. The goal is not to imbue robots with emotions, but to help them react flexibly, learn from collisions, and assist humans more safely in real-world environments.

From science fiction to the lab: robots begin to "feel"

For many years, the idea of robots with tactile sensations was seen only in movies. In real life, the concept was considered unnecessary because robots are insensitive tools. But that becomes a barrier when robots are used to assist humans in real environments.

In fact, when robots work in living spaces or hospitals, the lack of ability to react to unusual situations can lead to risks. This makes scientists start to ask the question again: should robots "feel" like humans to handle situations better?

To answer this, a team at the University of Cambridge and UCL has developed an artificial skin made from a conductive hydrogel that can mimic the way human skin transmits sensory signals. This skin allows the robot to accurately register physical stimuli from the environment.

According to Tuoi Tre Online 's research, many other research centers are also pursuing this direction, such as the Max Planck Institute in Germany or Seoul National University, with soft skin technologies that can self-heal and create precise tactile feedback.

Robots with tactile senses to act smarter

The feeling of pain in robots is not intended to replicate human emotions, but to serve a very practical purpose: to help robots respond more intelligently and safely during work. Integrating artificial skin that can detect impact force or abnormal temperature helps robots recognize when there is a risk of harm to themselves or to the people they are interacting with.

When robots are programmed to “feel pain,” they will adjust their force, change their position, or stop the operation if they notice anything unusual. This is extremely important in medical environments, where robots can assist patients or the elderly. A nursing robot with sensor skin will be gentler, knowing to “back away” if it encounters resistance, avoiding hurting the patient.

In the rescue field, the sense of temperature or vibration helps robots identify dangerous areas and quickly retreat. This technology is also expected to help people with disabilities: electronic skin attached to robotic arms helps them receive tactile feedback every time they move.

According to professor Fumiya Iida, the team's goal is to develop self-protective reflexes for robots, not to create emotions.

From touch to emotion: Where are the technological limits?

As robots can respond to pressure, temperature changes, or detect cuts, many are beginning to wonder: Are machines approaching the emotional realms that are uniquely human? While these reactions are entirely the result of programming, they increasingly resemble the way humans express pain, alertness, or fear.

It is this similarity that blurs the line between touch and emotion for the user. If a robot looks human and withdraws its hands when in danger, it is easy for the user to become emotionally attached, even feel understood.

In areas like mental health, early childhood education , or customer service, this can be a powerful tool for building empathy. But it also runs the risk of creating the illusion that robots actually have feelings, leading to dependency or misunderstanding of the technology.

Scientists emphasize that robots do not actually feel pain , have no consciousness or emotions. All behavior is just a response to pre-designed rules. The problem is that humans can interpret those reactions as emotional expressions, and that is the technological limit that society needs to talk more clearly about in the near future.

Source: https://tuoitre.vn/robot-biet-dau-nhu-con-nguoi-nho-da-nhan-tao-20250717102826532.htm

![[Photo] Cat Ba - Green island paradise](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F04%2F1764821844074_ndo_br_1-dcbthienduongxanh638-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[VIMC 40 days of lightning speed] Da Nang Port: Unity - Lightning speed - Breakthrough to the finish line](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/12/04/1764833540882_cdn_4-12-25.jpeg)

Comment (0)