A pioneer in growing flowers in greenhouses, 55-year-old Nguyen Dinh My never imagined that one day Da Lat would pay the price for a model once considered the agriculture of the future.

Having migrated from Hue to Da Lat in the 1950s, Mr. My's family represented a generation of migrants from the "scorching" provinces of Central Vietnam to this cool highland region. Taking advantage of the mild climate and diverse flower varieties, they gradually developed the flower farming industry, establishing the famous Thai Phien flower village.

Twenty-seven years ago, Mr. My was one of the first people in Da Lat to experiment with growing flowers in greenhouses – a method largely unfamiliar to farmers at the time. The model emerged in the 1990s when some foreign companies applied it to grow imported vegetables and flowers. This method yields nearly double the productivity compared to growing outdoors, because the sun and rain are no longer "a matter of nature," but are within the control of farmers like Mr. My.

Seizing the opportunity, he quickly set about building a greenhouse with all the pillars and frames made of bamboo, covered with flexible plastic nylon film, at a cost of about 18-20 million dong - equivalent to about 3 gold bars at that time. Experiments quickly yielded positive results. Chrysanthemums produced more beautiful colors when grown outdoors, and the plants were more uniform, resulting in higher yields. 1,000 square meters could generate an income of about 100 million dong per year.

Over the next five years, Mr. My invested and accumulated capital, expanding his greenhouse from an initial 300 square meters to 8,000 square meters. His flowers, initially sold only locally, now reached the entire country. Thanks to the profits from his greenhouse flower cultivation model, his family's life gradually improved; he built a multi-story house and sent his children to school.

Trade-off

In the 2000s, growing flowers in greenhouses became a trend in the agricultural sector in Da Lat, under the name "high-tech agriculture". In 2004, the Lam Dong agricultural sector had a separate development plan for this model. With government encouragement, greenhouses sprung up like mushrooms after the rain, especially in the flower villages of Thai Phien, Ha Dong, and Van Thanh. From being built with rudimentary bamboo, the greenhouses gradually transitioned to iron frames with investment costs of hundreds of millions of dong.

"Because it was profitable, everyone rushed to do it," Mr. My recounted.

More than a decade after investing in this type of farming, Mr. My's flower village has significantly improved. Farmers have accumulated wealth thanks to growing flowers in greenhouses. The flower villages have taken on a new look. Dilapidated single-story houses have been replaced with multi-story houses and villas. Many people have even bought cars. For several years in a row, greenhouses have been mentioned in local reports as a proud achievement in applying high technology to agriculture.

But greenhouses have distorted Da Lat's appearance.

"The Spring City," once covered in lush green pine forests, has gradually transformed into the milky white of greenhouses. More than 30 years after the first model appeared, Da Lat now boasts 2,907 hectares of greenhouses, accounting for over 60% of the city's vegetable and flower cultivation land. Greenhouses are built in 10 out of 12 inner-city wards, with a high concentration in Ward 12, where greenhouses occupy 84% of the cultivated area; followed by Wards 5, 7, and 8 with over 60%.

From initial excitement, over time, Mr. My gradually began to feel the downside. It was hotter inside the greenhouse than outside due to light radiation, and there was a buildup of toxins from pesticides sprayed on the flowers.

"I still have to work for the sake of the economy, for my livelihood," Mr. My explained.

Experts studying Da Lat all agree that not only farmers, but the entire city is paying the price for the rampant development of greenhouses. In recent years, images of the mountain city being flooded have appeared with increasing frequency and increasingly serious consequences. Like Ho Chi Minh City or Hanoi, Da Lat now also has "flood hotspots" whenever it rains, such as Nguyen Cong Tru, To Ngoc Van, Truong Van Hoan, Ngo Van So... Many vegetable and flower gardens along Trang Trinh and Cach Mang Thang Tam streets are regularly submerged from 0.5 to 0.8 meters.

Most recently, on the afternoon of June 23rd, a 30-minute rainstorm caused flooding of up to half a meter on many roads at the end of the Cam Ly stream, such as Nguyen Thi Nghia, Nguyen Trai, Phan Dinh Phung, and Mac Dinh Chi. The water flowed rapidly, sweeping away cars and flooding people's homes. This was the worst flooding in the past two years, following the heavy rain in September 2022.

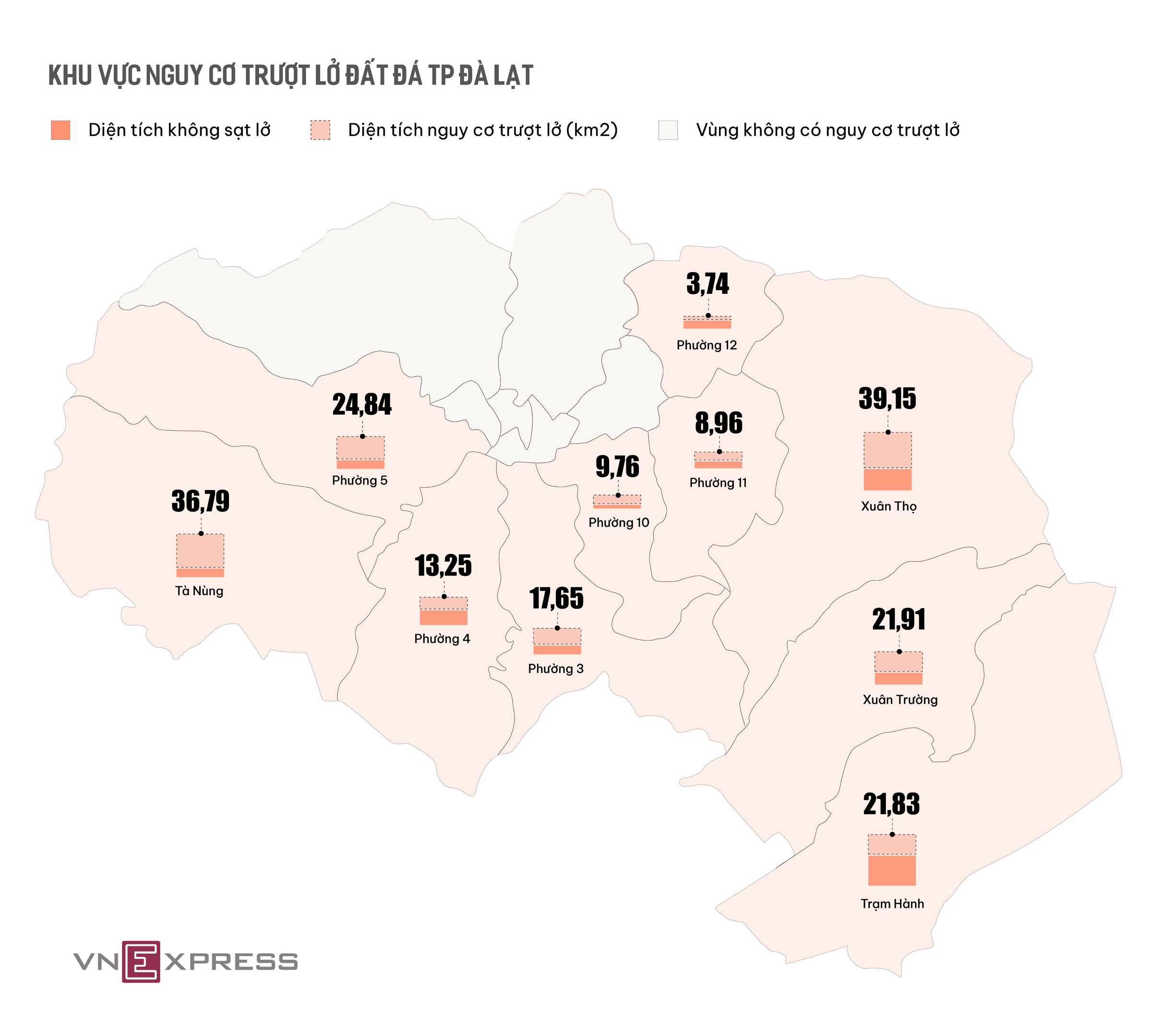

Along with flooding, landslides are also occurring with increasing frequency and severity. According to statistics from the Institute of Geological Sciences and Minerals, Da Lat City currently has 210 landslide and subsidence points, mainly on transportation routes. It is also one of the four localities in Lam Dong province assessed as having a high to very high risk of landslides, along with Lac Duong, Di Linh, and Dam Rong districts.

The Institute assessed that Da Lat has 10% of its area at very high risk of landslides, 42% at high risk, and 45% at medium risk; only 3% is at low risk. Over the past 10 years, the locality has suffered nearly 126 billion VND in losses due to various natural disasters, including landslides.

In late 2021, hundreds of cubic meters of soil on a hillside along Khe Sanh road fractured and slid down into the valley, more than 50 meters deep. The rocky embankment, trees, and a single-story house were buried, fortunately without causing any casualties. The landslide caused widespread tremors, resulting in cracks and exposed foundations in seven 3-4 story houses. Authorities had to urgently relocate many households in the surrounding area.

In the last two days of June, Da Lat experienced 13 consecutive landslides across the city. Among them, the landslide on Hoang Hoa Tham street on the morning of June 29th resulted in 2 deaths, 5 injuries, and damage to several villas.

Filling in streams and lakes.

According to Professor Nguyen Mong Sinh, former Chairman of the Union of Scientific Associations of Lam Dong Province, greenhouses are the main cause of soil erosion, degradation, flash floods, and flooding in Da Lat.

"The soil has no room to absorb water, and with the greenhouses covering everything, the rain flows in streams. The layers of roofing connected in succession create a large flow, and wherever it flows, it erodes that area," Mr. Sinh explained.

According to the Department of Crop Production of Lam Dong province, farmers' greenhouse designs are located close to drainage canals and ditches, without any setback space. In many places, the houses encroach on streams, obstructing water flow. Most structures lack a system of ponds, reservoirs, or drainage ditches. Residents living near roads discharge wastewater into the public drainage system, with some households even allowing it to flow directly onto the road. In areas without a separate rainwater harvesting system, water flows naturally into streams according to the terrain.

Sharing the same view, the Tay Nguyen Institute of Agricultural and Forestry Science and Technology believes that the dense growth of greenhouses and net houses adjacent to residential areas restricts the development of trees and prevents rainwater from draining. As a result, the soil retains a large amount of water. During unusual rainfall, severe erosion occurs. However, the institute argues that this is only one cause and that the entire problem cannot be blamed on the net houses and greenhouses.

Born and raised in Da Lat, Khieu Van Chi (67 years old, an engineer) witnessed the city's lakes and streams shrinking year after year, along with increasingly severe flooding that caused greater damage.

"There's nowhere left to hold the water," he said.

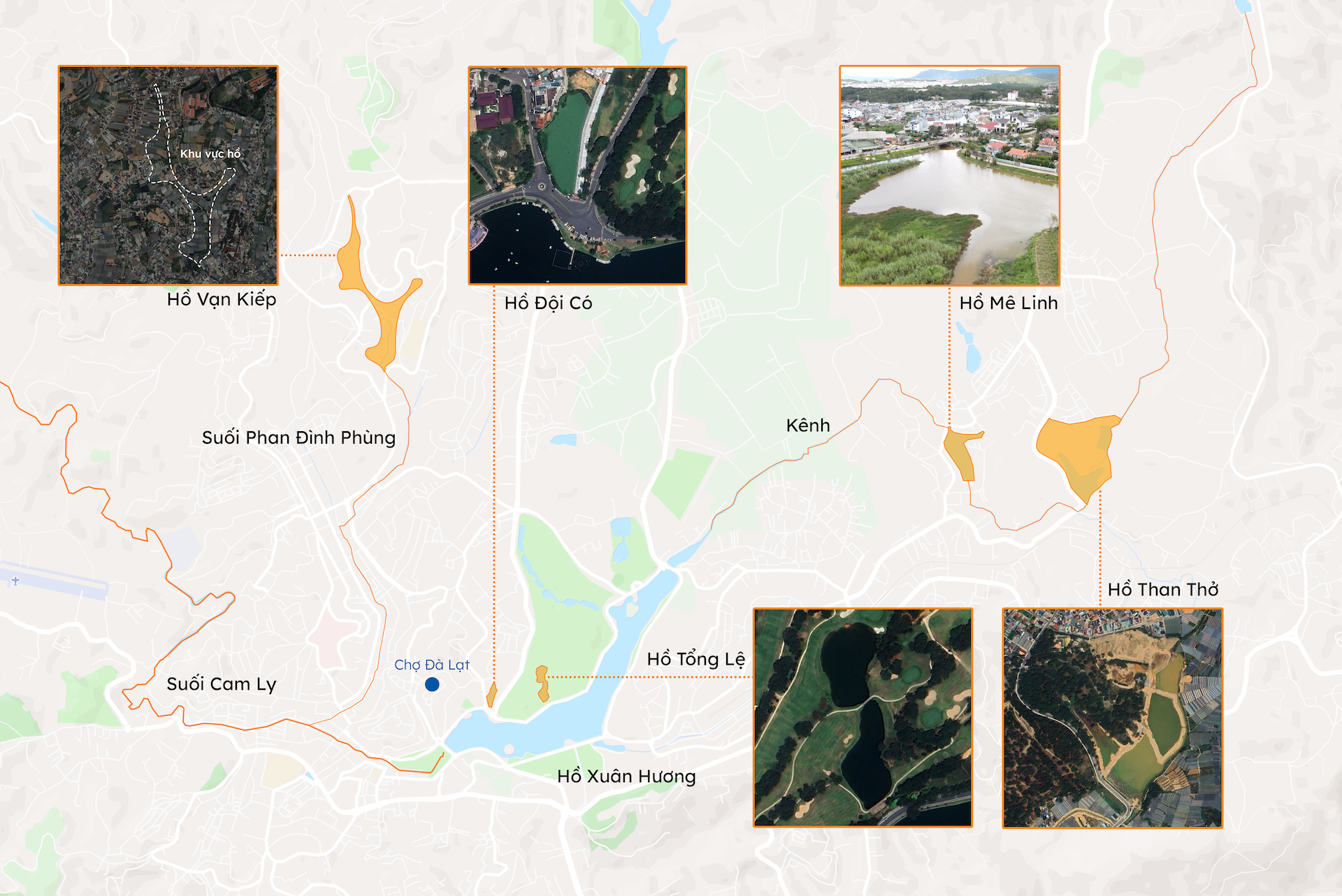

Da Lat has a hilly and mountainous terrain, so flash floods and landslides have been a long-standing problem. However, the damage is not severe because of the many large artificial reservoirs. Specifically, the Thai Phien basin has Than Tho Lake, and Chi Lang has Me Linh Lake. Downstream of Thai Phien and Chi Lang is Xuan Huong Lake, along with auxiliary reservoirs for smaller basins such as Tong Le Lake for the Cu Hill basin, Doi Co Lake for the Vo Thanh hamlet basin, and Van Kiet Lake for the upstream Thanh Mau basin of Phan Dinh Phung stream...

Mr. Khieu recalled that in the past, during heavy rains, water would flow into these lakes. With a system of dams and sluice gates, people could limit and regulate flooding.

Later, houses gradually encroached on forest land and retention ponds. Van Kiet Lake was "wiped out," Me Linh Lake and Than Tho Lake were encroached upon, their areas shrunken, and silted up. Secondary lakes like Doi Co and Tong Le were also reduced in both area and the connecting drainage pipes to the larger lakes. The stream flowing from the Dong Tinh and Nguyen Cong Tru areas, which used to be an open canal crossing Phan Dinh Phung Street, has now become a closed culvert. Both banks, once covered with vegetable gardens and reeds, are now densely packed with houses.

Currently, Da Lat only has one main drainage channel: the Cam Ly stream. The streambed is narrow and has not been dredged, retaining only 10-20% of its original width. This obstruction hinders water flow, causing flooding during heavy rains. For example, the 3 km stretch of stream from Thai Phien Lake to Than Tho Lake experiences flooding of vegetable gardens along its banks after every heavy rain.

According to architect Ngo Viet Nam Son, from the very first urban plans, the French paid great attention to water spaces by utilizing the terrain, rivers, streams, and building artificial regulating lakes. The purpose was to beautify the landscape and reduce flooding, before planning other spaces for housing and urban development. However, later on, the water spaces were no longer preserved as originally intended.

"The drainage infrastructure has not been invested in, and the rainwater drainage system is not separated from domestic wastewater, so not only is flooding increasing, but it is also causing environmental pollution. Meanwhile, Da Lat is experiencing rapid development, with continuous housing construction," Mr. Son expressed his concern.

Overloaded

This highland region is bearing too much burden due to its ever-increasing population. Previously, Da Lat's famous flower villages were built upon waves of immigration. Thai Phien flower village is largely inhabited by people from Hue, Binh Dinh, and Quang Ngai. Ha Dong flower village was formed by immigrants from Hanoi, and Van Thanh flower village by people from Ha Nam. These immigrants have been and continue to create a new generation in Da Lat.

"A family might have 3-4 children, and if they don't go to Saigon to work, they have to divide the land, build houses, and add in new immigrants. In the past, you could only see one house on one side and one on the other; now, houses are built close together," said Mr. Nguyen Dinh My.

Along with a local population boom, the "dream city" is welcoming more residents from developed cities like Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. However, Da Lat was not prepared for this wave of immigration.

In 1923, architect Hébrard's urban planning project for Da Lat envisioned a "city within greenery and greenery within the city." At that time, Da Lat had a population of 1,500, with a planned area of 30,000 hectares to accommodate 30,000-50,000 people. Exactly one century later, Da Lat has expanded to 39,000 hectares, with a population of approximately 240,000 people, an increase of more than 150 times, and nearly five times the planned area from 100 years prior.

Population growth has created pressure on housing. Migrants from other localities have come to Da Lat to buy land with handwritten documents and build houses without permits, violating planning regulations. A typical example is the residential area on Khoi Nghia Bac Son Street in Wards 3 and 10; before 2016, there were only over 180 households, but now there are approximately 100 more households outside the planned area. Authorities have held numerous meetings but have yet to resolve the issue completely.

Besides attracting residents, the "city of mist" is also a popular tourist destination. In 2006, Da Lat received only 1.32 million visitors, but this number reached 5.5 million in 2022, only decreasing during the two years of Covid-19. To meet the accommodation needs of tourists, the number of lodging establishments increased from 538 in 2006 to 2,400 in 2022, a fourfold increase.

Residential areas, villas, hotels, and homestays have sprung up en masse around the city and on the hillsides, reducing forest area. Forest cover decreased from 69% in 1997 to 51% in 2020. Specifically, pine forests within the city decreased from 350 hectares in 1997 to only 150 hectares in 2018, meaning more than half of the area was lost in just over 10 years, according to statistics from the Lam Dong Department of Agriculture and Rural Development.

Faced with the negative consequences of rapid development in Da Lat, the Lam Dong provincial government has reassessed the situation and implemented solutions to bring about change. Based on feedback from scientists, over the past five years, authorities have held numerous meetings to discuss ways to reduce the number of greenhouses. At the end of 2022, Lam Dong Vice Chairman Pham S announced a plan to completely eliminate greenhouses in the inner city of Da Lat before 2030, leaving only those in the surrounding communes. Several implementation roadmaps have been outlined to move towards more efficient outdoor agriculture.

The urban and housing development space in Lam Dong province is also being adjusted in its planning, with a focus on expanding the urban area towards satellite regions such as Lac Duong and Lam Ha.

In addition, the government invited Japanese experts to survey and consult on solutions to respond to landslides; and urban drainage experts to reassess the entire drainage system, while also allocating resources to invest in this issue.

In contrast to the calls from 10 years ago, the model of growing flowers and vegetables in greenhouses is no longer encouraged in central Da Lat. Some residents are also beginning to reconsider the city's rapid development in recent years, of which they were a part.

Mr. Nguyen Dinh My chose to buy more land in Lac Duong district - 23 km from Thai Phien flower village - to expand his greenhouse flower cultivation model. "This model is developing rampantly in the city. The government needs to do something about this; it's not good," he said, expressing his concerns about the negative aspects of greenhouse flower cultivation.

For locals like Mr. Khieu Van Chi, some losses are now just memories. Pointing to a spot on the map, the 67-year-old man said that this used to be Van Kiet Lake, one of the symbols of old Da Lat, but now the land is just covered with layers of white greenhouses.

Content: Pham Linh - Phuoc Tuan - Dang Khoa

Graphics: Dang Hieu

Source link

Comment (0)