New cave evidence suggests the Maya endured a devastating 13-year drought, helping to explain why their once-thriving cities declined. Source: Shutterstock

Researchers found that rainfall during the wet season had declined over several years, including a devastating 13-year drought. This natural disaster led to crop failures, abandoned construction, and the collapse of many southern Maya cities and the decline of powerful dynasties. This is considered the clearest evidence yet that climate change played a central role in the decline of Maya civilization.

Prolonged drought and the collapse of the Maya civilization

Inside a stalagmite in Mexico, scientists have found chemical traces that reveal a devastating 13-year dry spell, along with several other droughts lasting more than three years each. The team, led by the University of Cambridge, analyzed oxygen isotopes in the stalagmites to reconstruct rainfall patterns for each wet and dry season between 871 and 1021 AD. This is the Late Classic period, the period considered to be the decline of the Maya civilization. For the first time, scientists were able to distinguish between seasonal rainfall conditions during this turbulent period.

Visitors explore the 'Cathedral Dome', the largest chamber in Grutas Tzabnah (Yucatán, Mexico), and the origins of Tzab06-1. The artificial well 'La Noria' now illuminates the cave. Photo: Mark Brenner

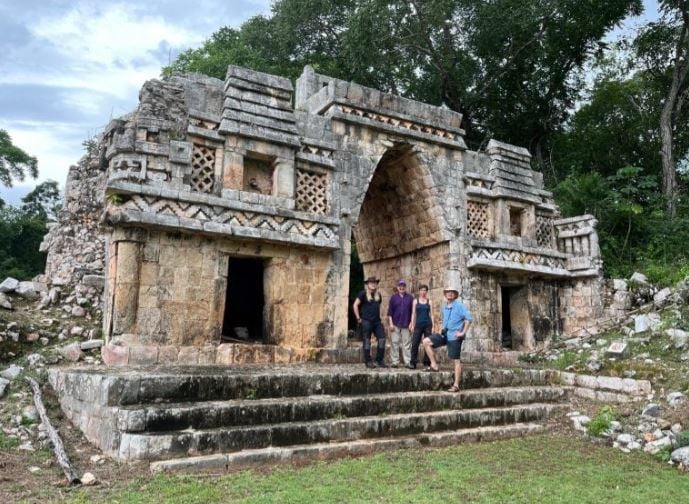

During the Terminal Classic period, many southern Maya cities – built of solid limestone – were abandoned. Dynasties collapsed, and a culture that had been the most powerful in the ancient world gradually moved north, losing much of its political and economic influence.

Archaeological evidence from caves in the Yucatán shows that there were eight separate droughts, each lasting at least three years. The most severe drought lasted 13 years. This data is consistent with archaeological evidence that monument building and political activity at major northern centers, including Chichén Itzá, halted at various points during the climate change.

By pinpointing the precise dates of droughts, the research offers a new scientific framework for examining the links between climate change and human history. The work was published in the journal Science Advances.

“This period in Maya history has attracted interest for centuries,” said lead author Dr. Daniel H. James. “There have been many hypotheses, including changes in trade routes, warfare, and severe drought. But by combining archaeological data with quantitative climate evidence, we are gaining a better understanding of what led to the collapse of Maya civilization.”

Daniel H. James, David Hodell, Ola Kwiecien, and Sebastian Breitenbach (LR) at the Maya site of Labna in the Puuc region (Yucatán, Mexico), which was likely abandoned during the Terminal Classic period. Source: Mark Brenner

Combining climatic and archaeological records

Since the 1990s, scientists have begun to piece together climate records with evidence left behind by the Maya, such as dates inscribed on monuments, suggesting that a series of droughts during the Late Classic period may have contributed to the socio-political upheaval in Maya society.

Now, James and colleagues from the UK, US and Mexico have used chemical traces in stalagmites from a cave in northern Yucatán to reconstruct these historical droughts in more detail.

Stalagmites are formed when water drips from the cave ceiling, carrying minerals that accumulate as sediment on the floor. By analyzing the oxygen isotopes in each layer and determining the exact age, scientists have been able to extract incredibly detailed climate information about the Late Classic period. Unlike lake sediments, which lack year-by-year data, stalagmites allow for details previously inaccessible to science.

“Lake sediments are useful for getting a general overview, but stalagmites offer the ability to capture fine detail, allowing us to directly connect the history of Maya sites with the climate record,” explains James, now a postdoctoral researcher at University College London (UCL).

Daniel H. James installs a drip rate monitor on a rock slab in Grutas Tzabnah (Yucatán, Mexico) as part of a larger cave monitoring campaign. Photo: Sebastian Breitenbach

Track the rainy and dry seasons

Previously, stalagmite studies had only determined average annual rainfall during the Late Classic period. However, the Cambridge team went further, separating wet and dry season data, thanks to stalagmite layers about 1mm thick that formed each year. Oxygen isotopes in each layer revealed details of drought conditions during the wet season.

“Knowing the average annual rainfall does not tell us as much as analysing the individual rainy seasons. It is the rainy season that determines the success or failure of the crop,” James stressed.

Prolonged drought, social crisis

According to stalagmite records, between 871 and 1021 AD, there were at least eight rainy season droughts lasting more than three years, including one lasting 13 years in a row. Even with the Maya’s advanced water management systems, such a long drought would have undoubtedly caused a serious crisis.

Remarkably, this climate data matches the chronology of the Maya monuments. During the prolonged drought, inscriptional activity at Chichén Itzá ceased completely.

Daniel H. James, Ola Kwiecien and David Hodell (LR) install the SYP automated drip water sampler at Grutas Tzabnah (Yucatán, Mexico) to analyze seasonal changes in the chemical composition of drip water. Photo: Sebastian Breitenbach

Survival through ritual

“This does not mean that the Maya completely abandoned Chichén Itzá, but it is possible that they faced more pressing issues such as securing food rather than continuing to build the monument,” James said.

Researchers also assert that stalactites from this cave and others in the area will play an important role in further unraveling the mysteries of the Late Classic period.

“In addition to helping us better understand the history of the Maya, the stalagmites may also reveal the frequency and severity of tropical storms,” James noted. “This is a demonstration of how methods typically used to study the distant past can be applied to the relatively recent past, providing new insights into the relationship between climate and the development of human societies.”

Source: https://doanhnghiepvn.vn/cong-nghe/13-nam-han-han-lien-tiep-manh-moi-ve-su-sup-do-cua-nen-van-minh-maya/20250823031541059

![[Photo] Parade to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Laos' National Day](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F02%2F1764691918289_ndo_br_0-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

![[Photo] Worshiping the Tuyet Son statue - a nearly 400-year-old treasure at Keo Pagoda](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fvphoto.vietnam.vn%2Fthumb%2F1200x675%2Fvietnam%2Fresource%2FIMAGE%2F2025%2F12%2F02%2F1764679323086_ndo_br_tempimageomw0hi-4884-jpg.webp&w=3840&q=75)

Comment (0)